THE DOOR OF THE MONTECASSINO ABBEY

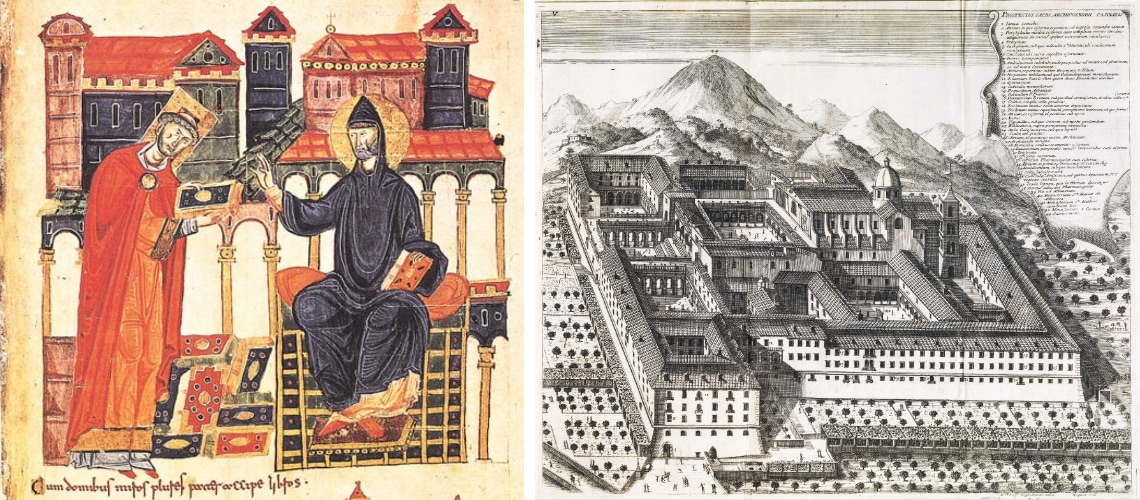

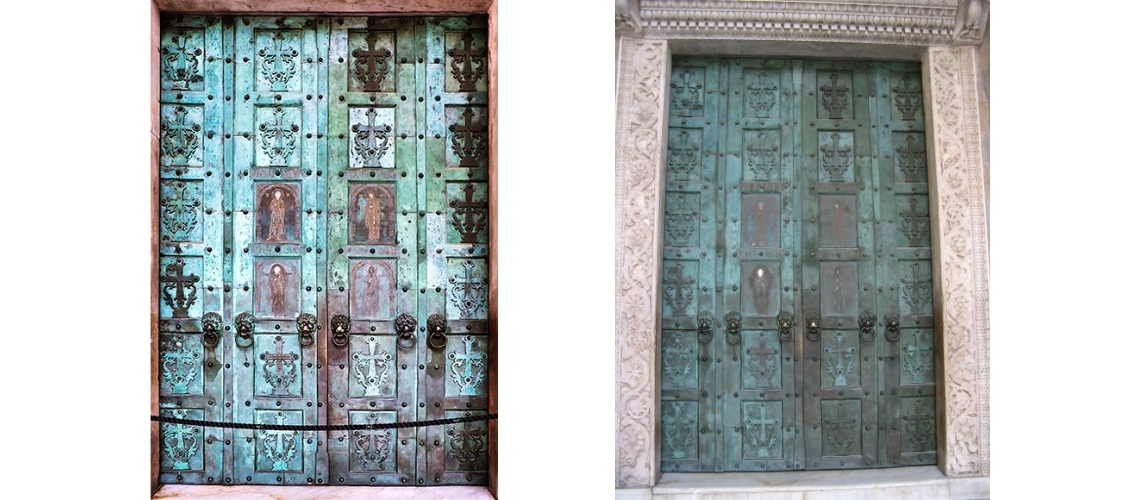

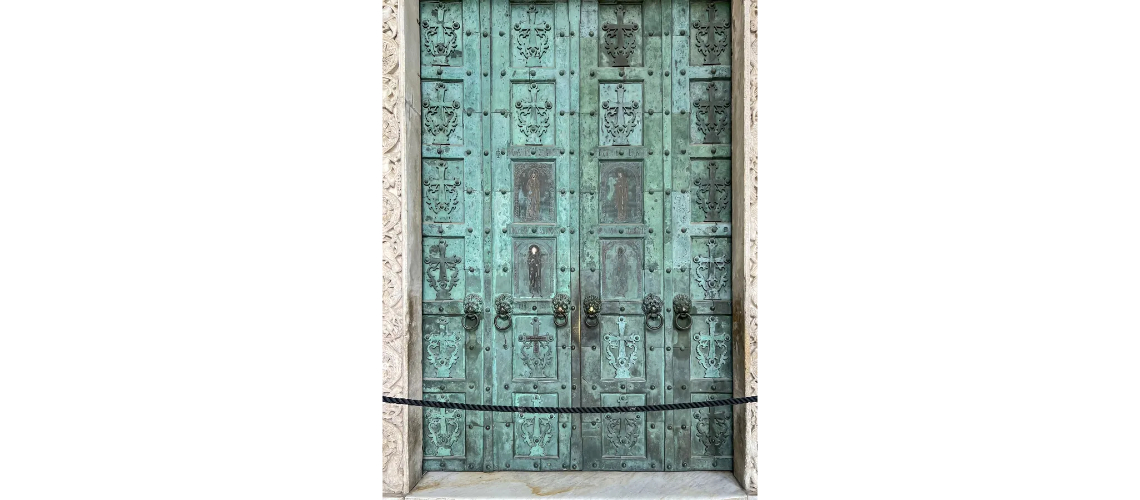

Desiderio, descendant of a princely family from Benevento, became abbot in 1058 [Photo 1]. The Cassino monk Leone Marsicano in the “Chronica monasterii Casinensis” wrote that around 1065 the abbot Desiderio, while he was architecturally renovating the monastic complex of Montecassino (the reconstruction took 5 years) was struck by the beauty of the bronze door of the Amalfi cathedral [Photo 2,3]:

“Since his eyes were enchanted, he immediately sent the measurements of the door of the old church to Constantinople, along with the order to build the door as it is today. He had not yet decided to rebuild the church: this is why the door was so low, as it remains today.”

| 1 – Desiderius symbolically donates the assets of the Abbey of Montecassino to St. Benedict | 2 – The Abbey of Montecassino, E.Gattola, Historia abbatiae Cassinensis, Venice 1733 |

3 – The Abbey of Montecassino before its destruction in 1943

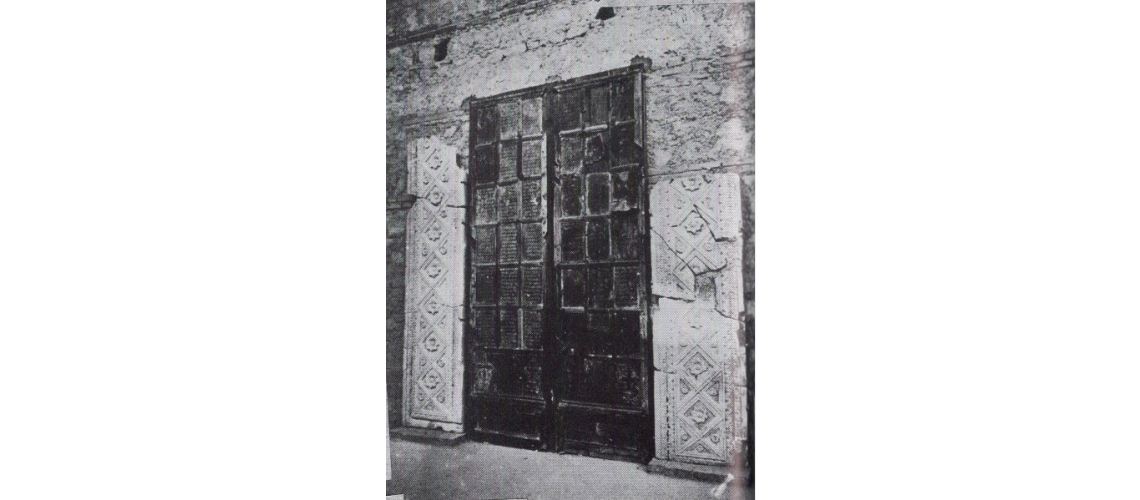

It is the second gate in chronological order, created in Constantinople and shipped to Montecassino. Like the one in Amalfi, it was built by nailing panels and frames to a heavy, thick wooden frame.

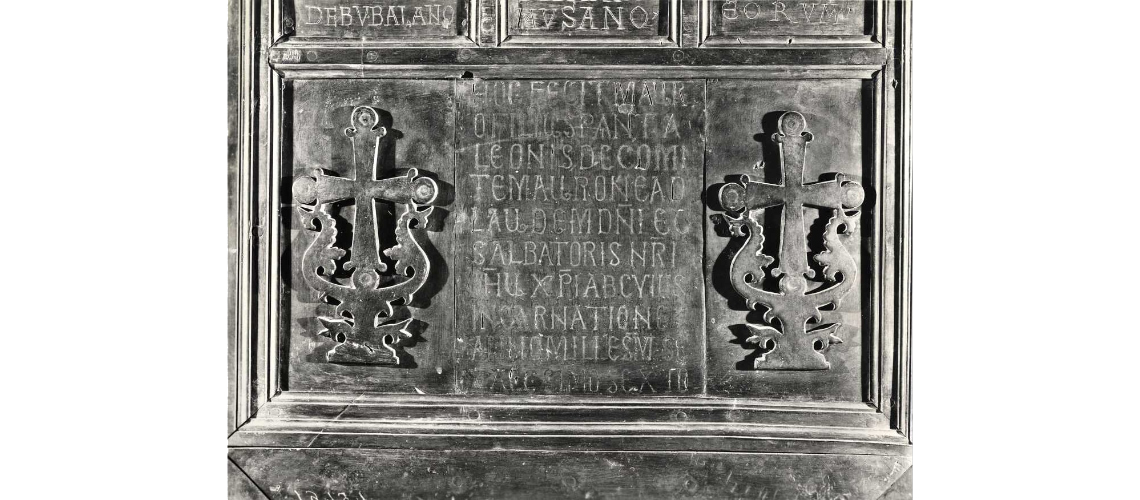

The door has two dedicatory inscriptions at the bottom (flanked by flat crosses similar to those of Amalfi), the left one bears the name of the donor Mauro di Amalfi and the date 1066, the year of their execution [Photos 4, 5, 6, 7, 8].

| 4 | 5 |

6

7

8

Above these, the doors are occupied by 18 panels each inscribed with the list of the monastery’s possessions [Photos 9, 10, 11, 12]. However, it should be noted that the typology of the decorations on the doors of Amalfi and Montecassino is very different: in Amalfi the four central panels are inlaid with Christ, the Virgin, St. Andrew and St. Peter, all the other panels feature flat crosses; in Montecassino the door is practically a long inscription with only four of the crosses at the bottom. It is very unlikely that Desiderio requested 36 panels all inscribed with the 180 possessions of Montecassino. The study of this list has highlighted that 26 of the 180 possessions inscribed on the door were purchased by Montecassino after 1066, most of which after the death of Desiderio (1087). But the current form of the gate and its dating are highly controversial:

the “Chronica monasterii Casinensis” reports that in 1123: “around this time Abbot Oderisio ordered the beautiful bronze door at the entrance of our church to be made.” It is very likely that the origin of the gate bearing the list of Montecassino’s possessions is due to Abbot Oderisio II, who ruled the Abbey from 1123 to 1126.

| 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 |

When Montecassino was bombed in 1944, the door panels had come loose, and it was discovered that eight of them had inlaid figures of saints and prophets on the back [Photos 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]: the Desiderius door, which came from Constantinople, with Byzantine inlaid panels and built just a few years after the Amalfi one, must have been dismantled and reassembled with the panels turned, on which the inscriptions with the properties of the Montecassino monastery had been engraved; the reassembly with the turned panels and the inscriptions is probably what is attributed to Oderisius II in the “Chronica monasterii Casinensis” in 1123.

The two large panels at the base of the doors, with the crosses, were added by Desiderius to make the door, which had been ordered too small, appropriate for the size of the entrance.

13-Door reassembled after the bombing of 1944

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |