The Bronze Door of Bohemond's Mausoleum in Canosa di Puglia

Bohemond of Hauteville, Duke of Antioch

Anna Comnena (1083-1153), daughter of Alexius I Comnenus, Emperor of Byzantium (1048-1118), in the “Alexeide”, the biography of her father Alexius I written by her, describes the Norman Bohemond of Hauteville (1051-1111), in those years her father’s enemy, but by whom she was evidently fascinated:

“Era un uomo tale, per dirla in breve, quale nessuno come lui fu visto nella terra dei Ro-

mani né barbaro né Greco; costituiva, infatti, stupore degli occhi al vederlo e sbigottimento a sentirne parlare… nella statura fisica era alto tanto da superare di quasi un cubito tutti gli uomini più alti, era stretto di ventre e di fianchi, largo di spalle, ampio di petto, forte di braccia, e in tutta la struttura del corpo non era né esile né corpulento, ma ottimamente proporzionato e, per così dire, conformato al canone di Policleto; vigoroso di mani e ben saldo sulle piante dei piedi, robusto nel collo e nelle spalle; …la carnagione, in tutto il resto del corpo, era bianchissima, ma il volto si arrossava col bianco, i suoi capelli tendevano al biondo,… gli occhi azzurri esprimevano, nel contempo, coraggio e gravità. Il suo naso e le narici spiravano liberamente l’aria, che attraverso il petto assecondava le narici e attraverso le narici l’ampiezza del petto; …si manifestava in quest’uomo un che di piacevole, che, però, era infranto dallo spirito spaventoso che promanava da tutte le parti; infatti l’uomo, in tutta la sua persona, era totalmente spietato e selvaggio, sia per la sua possanza che per il suo sguardo…”

“He was, to put it briefly, a man like no one else in the land of the Romans, whether barbarian or Greek; for it was a wonder to the eye to see him and a dismay to hear of him… in physical stature he was so tall that he surpassed all the tallest men by almost a cubit, he was narrow in belly and hips, broad in shoulders, broad in chest, strong in arms, and in the whole structure of his body he was neither thin nor corpulent, but excellently proportioned and, so to speak, conformed to the canon of Polyclitus; strong in hands and firm on the soles of his feet, robust in neck and shoulders; … his complexion, in all the rest of his body, was very white, but his face was red with white, his hair was verging on blond,… his blue eyes expressed, at the same time, courage and gravity. His nose and nostrils freely breathed the air, which through his chest followed his nostrils and through his nostrils the breadth of his chest; …there was something pleasant about this man, which, however, was shattered by the fearful spirit that emanated from all sides; for the man, in his entire person, was utterly ruthless and savage, both in his power and in his gaze…”

The French chronicler Orderic Vitalis (1075-1142) in his “Historia Ecclesiastica” tells us, however, that Bohemond’s real name was Mark, and that his Norman father Robert Guiscard (Duke of Apulia and Calabria, 1015-1085), having learned the legend of the biblical giant Behemoth, nicknamed him Bohemond.

He participated in the Epirus campaign against the Byzantines, was a commander in the First Crusade called by Pope Urban II in 1096 (led by Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond of Toulouse, and Godfrey’s brother Baldwin), becoming lord of the Principality of Antioch (Photos 1, 2).

| 1-Bohemond and the patriarch Daimbert sailing towards Puglia, Histore d’Outremer, 13th century | 2-Coin (follis) of Boemond, 1098-1111 |

Upon his death in 1111, Bohemond of Hauteville was buried in the mausoleum erected by his mother, Aberarda, adjacent to the south façade of the transept of the Cathedral of San Sabino in Canosa di Puglia, modeled on the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (Photos 3, 4). And it is at its entrance that the medieval bronze door, probably the most fascinating of the ancient doors, is located.

| 3 | 4 |

The Bronze Door

Together with the door of the Palatine Chapel in Palermo, this is the first Norman commission and dates back to the first half of the 12th century. It replaces the Byzantine model with Islamic stylistic references and revives the Western tradition of solid bronze casting, without a wooden core.

It was thanks to trade between the 10th and 11th centuries and the strong presence of Western merchants in the Islamic East that Islamic-manufactured objects reached the West, favoring the introduction of Arabic ornamental elements.

The door is 260 cm high and 202 cm wide, and is made up of two unequal panels, slightly different in height (Photo 5): the left panel is made from a single cast bronze slab approximately 4 cm thick. An ancient gap at the back was filled with the addition of a later slab (Photo 6); the right panel, on the other hand, is made up of four separately cast panels joined together by interlocking bronze bars. The two panels are so different that they cannot be made simultaneously and in a coordinated manner.

| 5 | 6 |

The composition of the door’s bronze alloy is 71.6% copper, 10.81% lead, and 16.18% tin for the right door; 65.53% copper, 14.72% lead, and 18.53% tin for the left door.

It is not entirely clear why the left door is made of a single 4 cm thick sheet, while the right door is composed of four cold-joined sheets, about half as thick. The joints are concealed by the frames cast directly onto each of the four sheets, and are overlapped in a symmetrical pattern (Photos 7, 8). The difference in the execution of the two doors (one whole and one in 4 parts), the difference in the decorations: the left one is “smooth” and the right one is crossed by horizontal joining frames, the left one with three 30 cm diameter discs positioned symmetrically, and the right one with two smaller discs positioned at the top and bottom and with a very different type of decoration from that of the discs on the left, the decoration of the two central panels in damascening with characters from the Altavilla family, suggest that two doors were cast at different times.

| 7 | 8 |

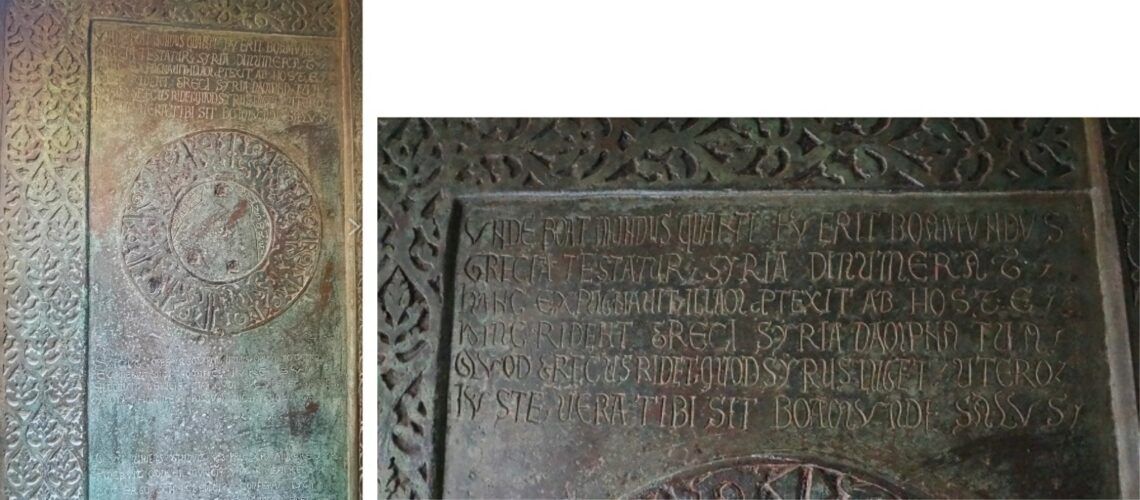

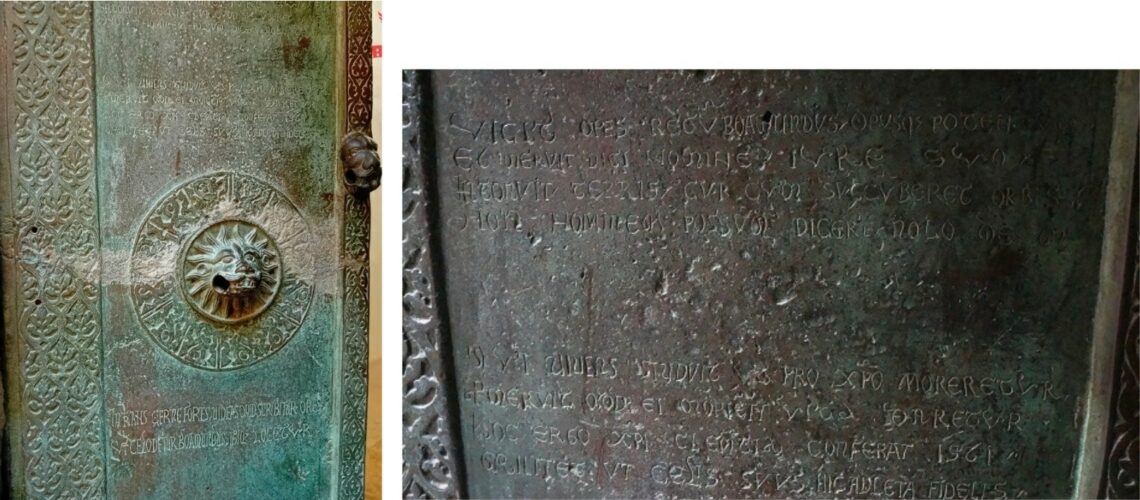

The right door was certainly and specifically cast for Bohemond’s mausoleum immediately after it was built. The left door, however, is most likely reused, as evidenced by the two interventions that adapted it to its new purpose: the long Latin inscription in praise of Bohemond, whose text continues the one surrounding the dome of the mausoleum and which was interspersed among the existing decorative elements, inserted piecemeal into the free spaces of the door (Photos 9, 10, 11, 12);

| 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 |

the other intervention consists of two applications at the centre of the two upper discs after having scraped away from them the original six-petal flower visible at the centre of the lower disc (Photo 13): on the central disc the lion’s head door-holder was applied (Photos 14,15), on the upper one a small sculpture of the Madonna and Child (no longer existing) was applied, as H. Swinburne testifies since the 18th century in “Voyages dans les deux Sicilies en 1777” and as demonstrated by the three recesses for the attachment and the writing surrounding it MARIA MATER DEI and IHS FILIUS MARIAE (Photos 16, 17); the left door, reused, was then personalised, Christianised and, in part, westernised.

| 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 |

17

Imagining the door before its reuse, we see that it features abstract ornamentation in very low, two-dimensional reliefs, graphic rather than plastic, typically Islamic. The repeated motif in the circular rings of the discs is an imitation of Kufic script and has no meaning (though perhaps the word “yumn,” meaning “happiness,” also found in contemporary decorations in the Palatine Chapel in Palermo, appears in all three). It could be a local creation imitating Islamic artifacts, perhaps made years earlier. Indeed, it was thanks to trade between the 10th and 11th centuries and the strong presence of Western merchants in the Islamic East and the West that Islamic objects arrived, favoring the introduction of Arabic ornamental elements into Western artifacts.

In the right door, the two smaller discs feature dense Kufic-style plant decorations, with horse figurines visible in the upper one. above the lower one (Photo 18,19) an inscription tells us that the author of the door was Ruggero da Melfi: “Sancti Sabini Canusiii Rogerius Melfie campanarum fecit has ianuas et candelabrum”; the decorations engraved in the two central panels with characters of the Altavilla family would seem to be imitations of Byzantine damascening but only a few details such as the faces, feet and hands are inlaid in silver, while the rest of the figures have engravings so thin that they do not allow the insertion of the silver thread of the damascening; and furthermore the overall style, especially that of the clothes, is more Western than Byzantine. In the upper panel Bohemond and his brother Ruggero are depicted kneeling in front of a small sculpture of the Crucifix which has been lost (as demonstrated by the traces and the two quadrangular support holes), in the upper panel the three standing figures are said to be Ruggero II, Guglielmo and Tancredi holding hands.

| 18 | 19 |