THE DOOR OF AMALFI CATHEDRAL

Bronze doors in Italy made in Constantinople

Of the ten bronze doors made in Constantinople and sent to Italy, only eight remain in their original locations: in the Amalfi Cathedral, in the Abbey of Montecassino, in San Paolo fuori delle Mura in Rome, in San Michele Arcangelo on Monte Sant’Angelo, in San Salvatore de Birecto in Atrani (moved to the collegiate church of Santa Maria Maddalena), in the Cathedral of Salerno, in the central door of San Marco in Venice, and in the door of San Clemente. The one from 1099, sent as a gift by Godfrey of Bouillon and placed at the entrance to the façade of Pisa Cathedral, was destroyed in the fire of 1595, and the one from the Basilica of San Martino in Montecassino (mentioned in the Abbey’s “Chronica”) was also lost.

Constantinople was the Mediterranean center of luxury goods production and trade, and was particularly renowned for its metalwork. Yet incredibly, no similar gate has survived, either in the metropolitan area or anywhere else in the empire; only the seven gates that reached Italy are known.

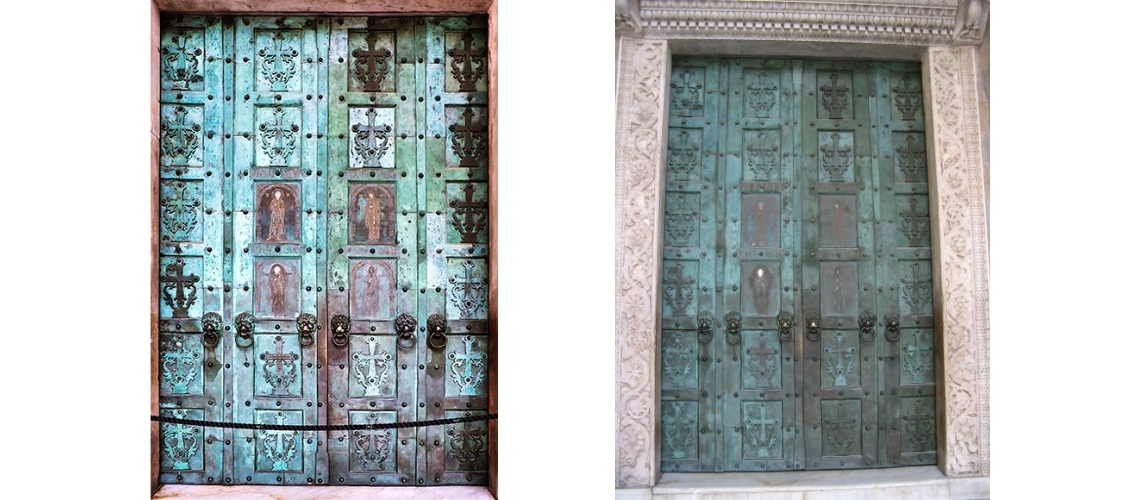

While Carolingian and Ottonian (or even Romanesque) gates are solidly cast, Byzantine gates are made of thin panels (about 3 millimeters thick) separated and nailed to a wooden frame. The individual panels were enclosed by modular frames (flat, as in the Amalfi Cathedral, or semi-circular or cordoned) [Photo 1] whose pieces were also nailed to the wood. Ultimately, they were wooden doors covered with thin panels and brass frames.

Photo 1

The Byzantine doors do not have any raised parts, with the exception of the lion heads supporting the door knocker. The aim was to create a shiny, pictorial and not plastic surface, unlike that of the medieval doors created in the West.

The Amalfi Door

The first of the group was that of Amalfi Cathedral, commissioned around 1060 by the very wealthy Amalfi nobleman Pantaleone de Comite Maurone, who had settled in the Constantinopolitan merchant colony founded by the Amalfi people in the 9th century. The most influential figure in the colony, he had been awarded the titles of “hypatos” and “dishypatos” (consul and consul again) by the Byzantine imperial court.

Pantaleone donated it to the cathedral of his hometown, dedicating the gate to Saint Andrew for the forgiveness of his sins and the redemption of his soul, as appears from the inscription engraved on the cross in the panel below that of Saint Andrew, along with his family lineage [Photos 2, 3]. We know that the cross in the panel below that of Saint Peter (now lost and replaced with a plain cross) bore the inscription in Latin and Greek with the name of the founder, Simeon.

| Photo 2 | Photo 3 |

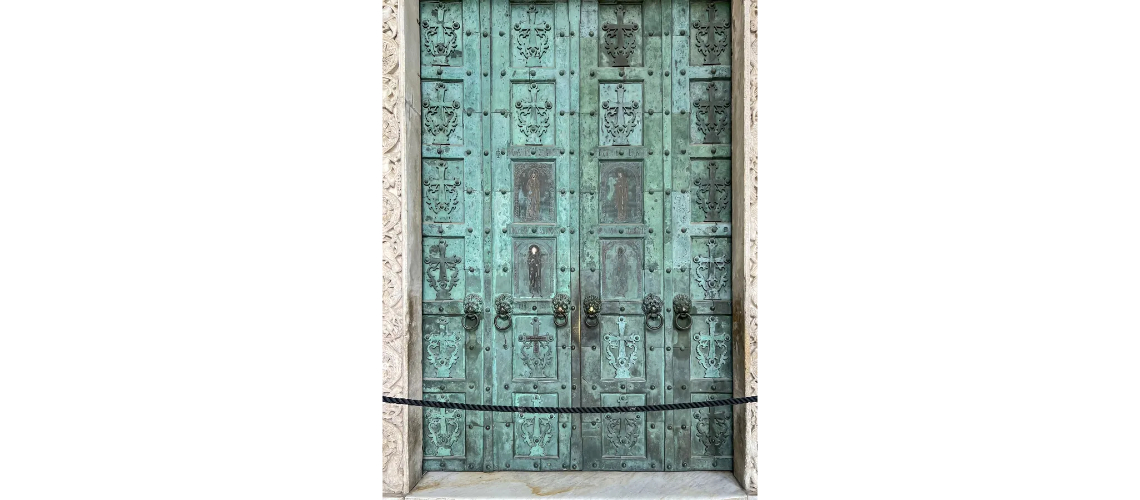

It consists of twenty-four brass panels (not actually bronze, but brass, as the alloy contains a high percentage of zinc): Byzantine doors were normally cast in brass, which, thanks to its yellow color, shone with golden reflections and were therefore not patinated but rather continuously washed to keep them shiny. Of these, twenty panels have applied flat, smooth, thin crosses, probably sand-cast, each secured with four hemispherical-headed pins [Photo 4].

Photo 4

The four central panels [Photos 5,6] instead have inlaid copper and silver figures of Christ [Photo 7] and the Virgin at the top [Photo 8], of Saint Andrew [Photo 9] and Saint Peter [Photo 10] at the bottom, under arches supported by two columns. The inlaid engraving was done cold on the smooth sheets of the panels which had also already been sand-cast.

| Photo 5 | Photo 6 |

| Photo 7 | Photo 8 |

| Photo 9 | Photo 10 |

Six lion heads were applied to support the door knocker, the only elements in plastic relief in the entire work [Photo 11, 12].

| Photo 11 | Photo 12 |