Donatello and the putti in the sculptures - Part I

The Putti in history

In the history of Western art the ancestor of the Renaissance “putto” appears in Greece in the form of the young Eros, god of sexual love and desire, but also a divine principle that pushes towards beauty. He is the son of Aphrodite and Ares. It is already mentioned in the 8th century BC from Hesiod in “Theogony”; Euripides, in the fifth century BC, in “Medea” describes him as a creative and procreative force with the aspect of a beautiful and shining youth with golden wings. In addition to the wings it has the attributes as the bow and the arrows with which it pierces the soul and heart of humans, provoking desire.

In the Roman Pantheon it becomes the god called Amor or Cupidus with the same attributes of Eros, sometimes it also has a torch, a marriage symbol. Apuleius in the Golden Donkey (2nd century AC) still describes him as a beautiful winged young man.

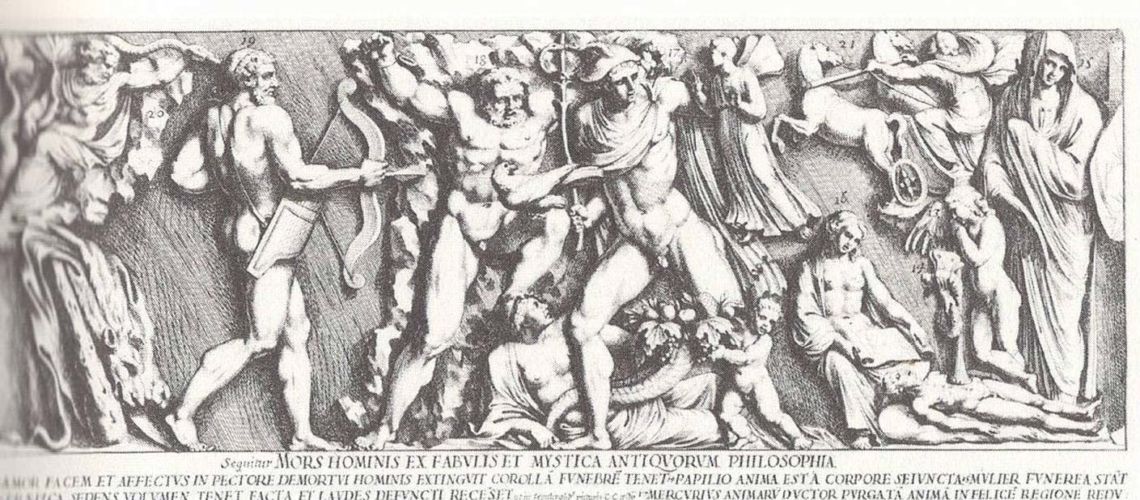

A naked and winged young man who extinguishes a torch on the dying man’s chest is, in some Roman sarcophagi, the spirit of death (Roman sarcophagus with the myth of Prometheus, Prince Cammillo Panphili collection, from: Admiranda Romnarum Antiquitatum, Roma 1691).

But over the years the Eros-Cupid have been rejuvenated, not only, but in Hellenistic and Roman art there is also a swarm of Cupids that keep company to the Gods and that go to decorate architectural parts and sarcophagi, Pompeian frescoes, gems and seals, with or without wings. We are approaching the putto model that will be resumed at the beginning of the ‘400.

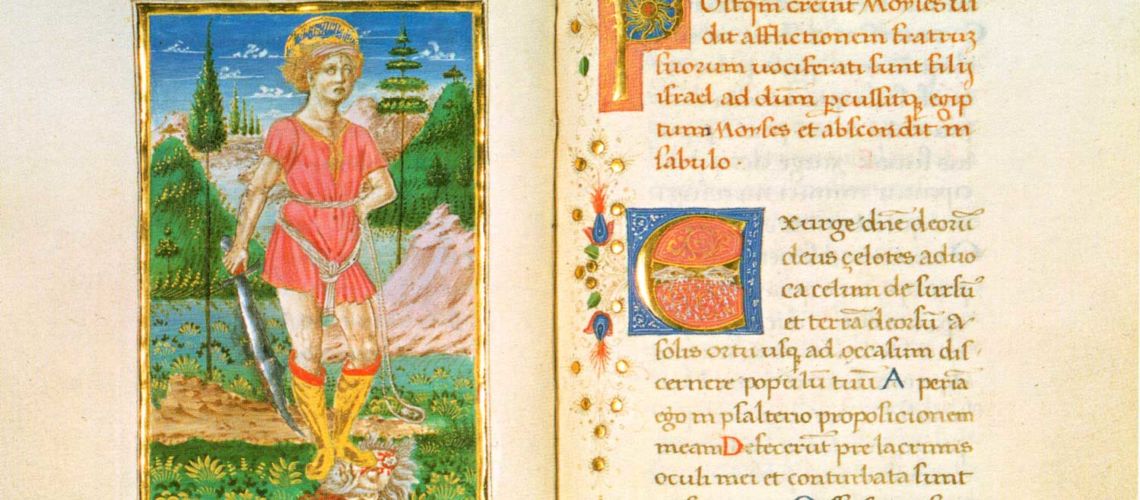

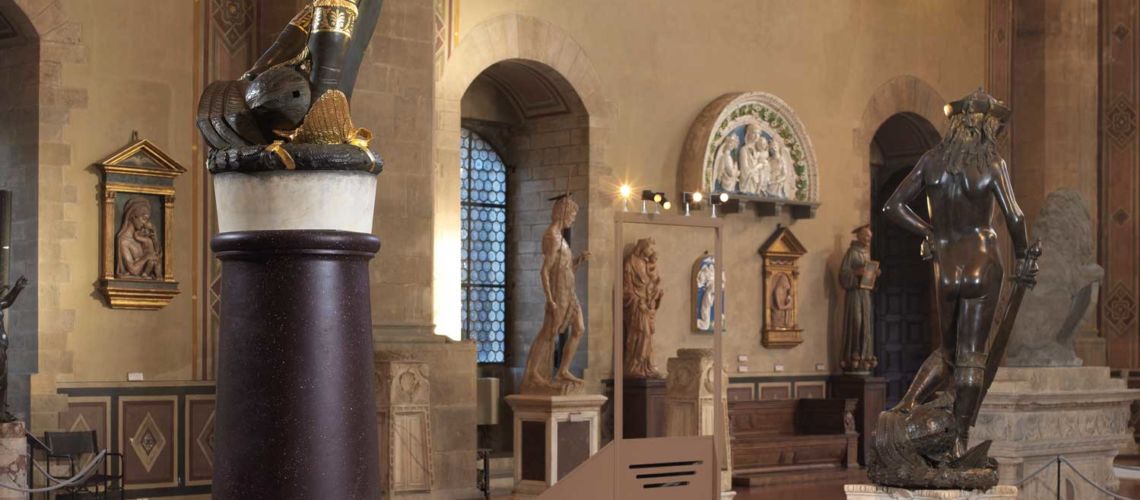

The bronze of Eros Dormiente from the 2nd century BC (Metropolitan Museum of art in New York) shows the typology that inspired the Renaissance sculptors: the child is very young, plump, with small wings of feathers, with curly and tousled hair.

Another model for the artists of the 15th century was also the marble sculpture of the 2nd century BC, now in the Uffizi Gallery, which was in the collections of Lorenzo il Magnifico.

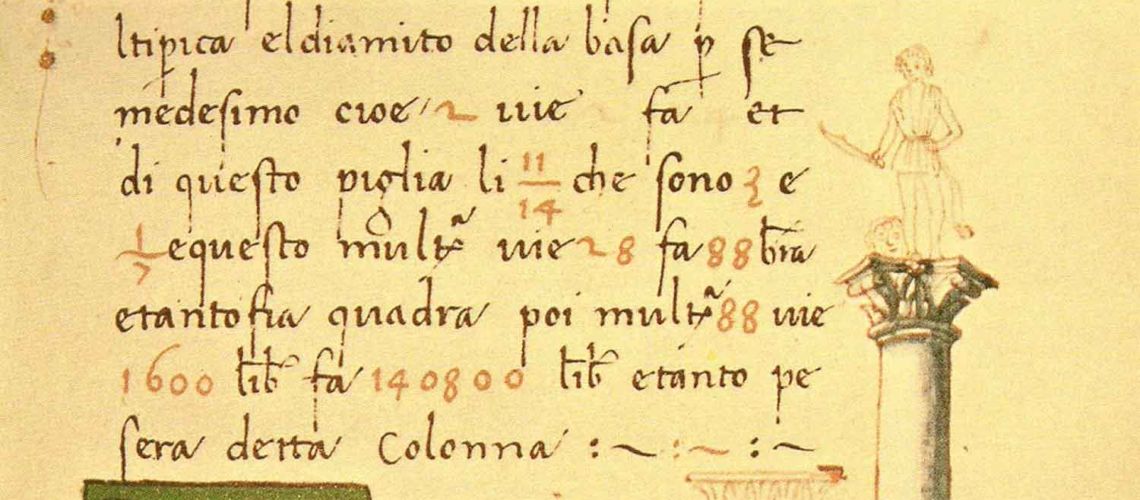

A further example of a putto was that which strangles the goose, a Roman copy (110-160 AD) of an Hellenistic original sculpted by Beithos of Calcedonia (Musei capitolini, Roma). An example in lost wax cast bronze from the mold executed on the original is also present at the Bazzanti Gallery of Florence.

Bronze casting in limited edition from original mould at Galleria Bazzanti, Firenze

In the art of the Eastern Roman Empire born in the 5th century, which later became Byzantine art, the putti go out of fashion and are not used as Christian symbols: they tend to disappear. A rare exception is the famous ivory Veroli Casket at the British Museum dating back to around the year 1000.

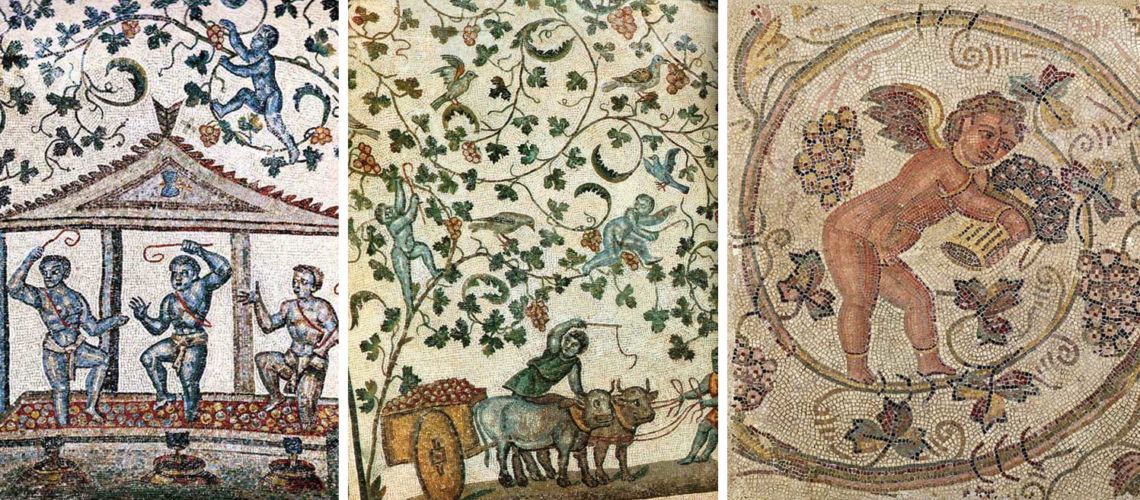

Early Christianity transforms Eros-Cupid into a tutelary spirit assigned to each child (the future guardian angel), but in the paintings of the catacombs and in the decorations of the early Christian churches, putti appear that harvest and make wine, thus transformed into Eucharistic symbols of immortality.

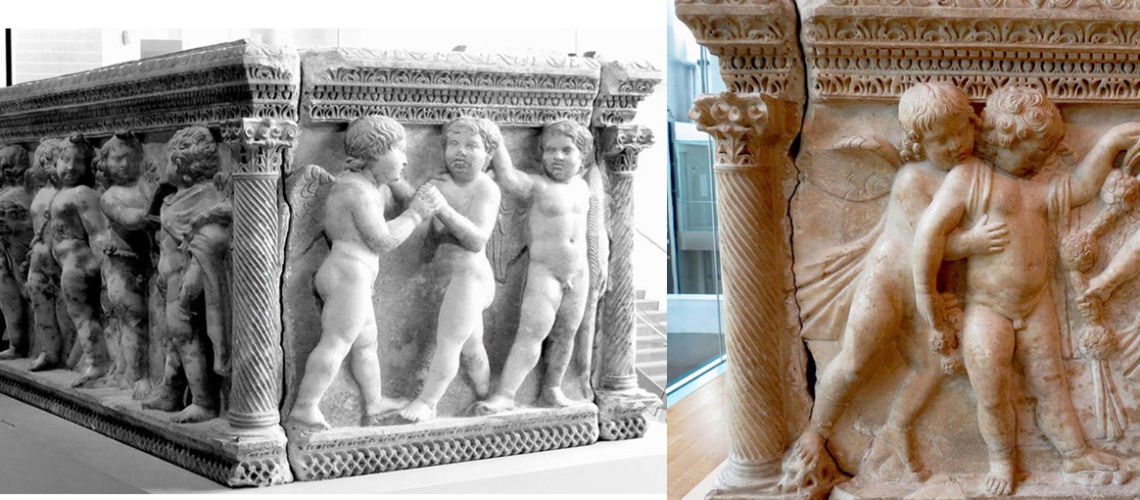

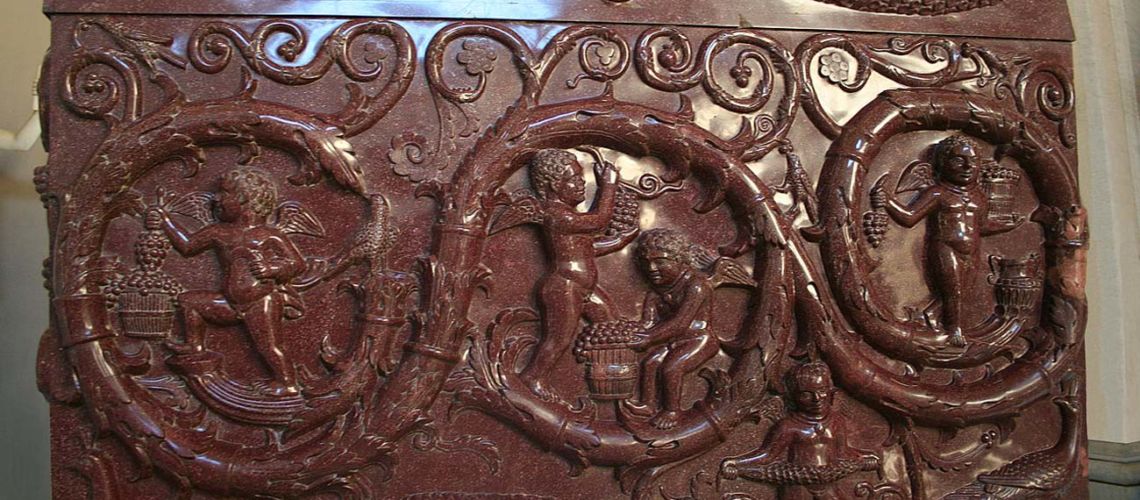

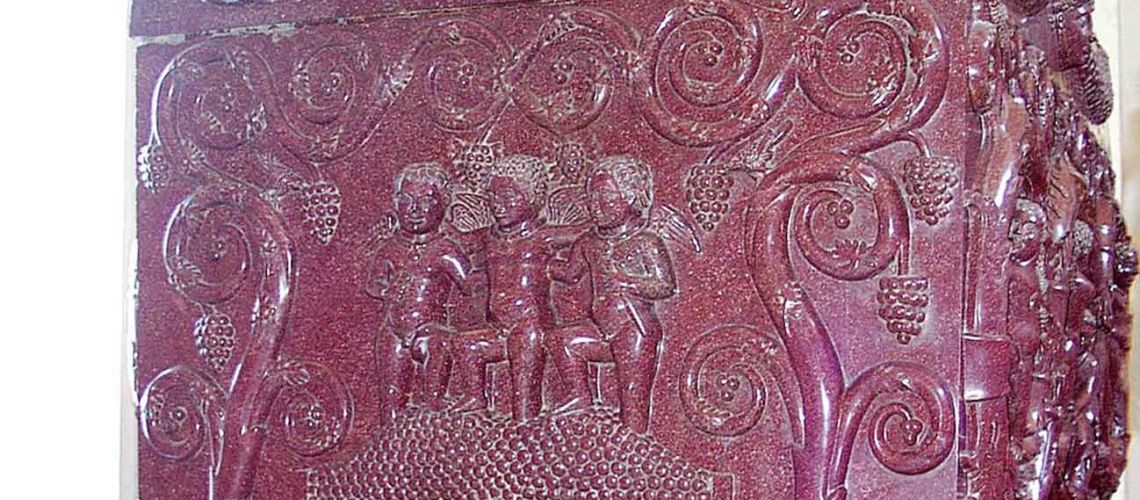

Famous are those of the great porphyry sarcophagus of Constantina, wife of Constantine, from 354 AC (Vatican Museum).

The Greek daemon, messenger of the gods that brings the news to men, joins the concept of genius that accompanies man during his life. Apuleius in De Deo Socratis of the 2nd century AC writes that the soul of man is the daemon, called genius in alive, and lemur in the dead. Later on Christianity moves away from paganism trying to make its components negative and diabolical, especially if related to sex. The daemon becomes an evil spirit linked to black magic and to the devil. The god Pan (who became for the Romans Silvanus and approached to satyrs), for example, god of the woods and pastures that was often represented as Dionysus and Priapus with great sexual attributes,

was transformed into the devil, to whom the same attributes were attributed: horns, animal face, part of the body with animal hair, goat legs, small tail, large animal phallus.

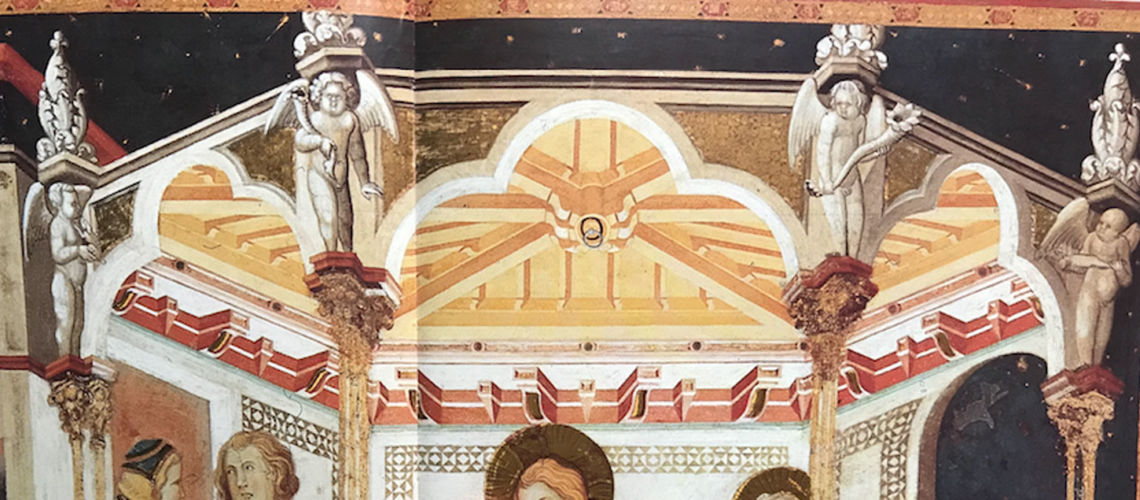

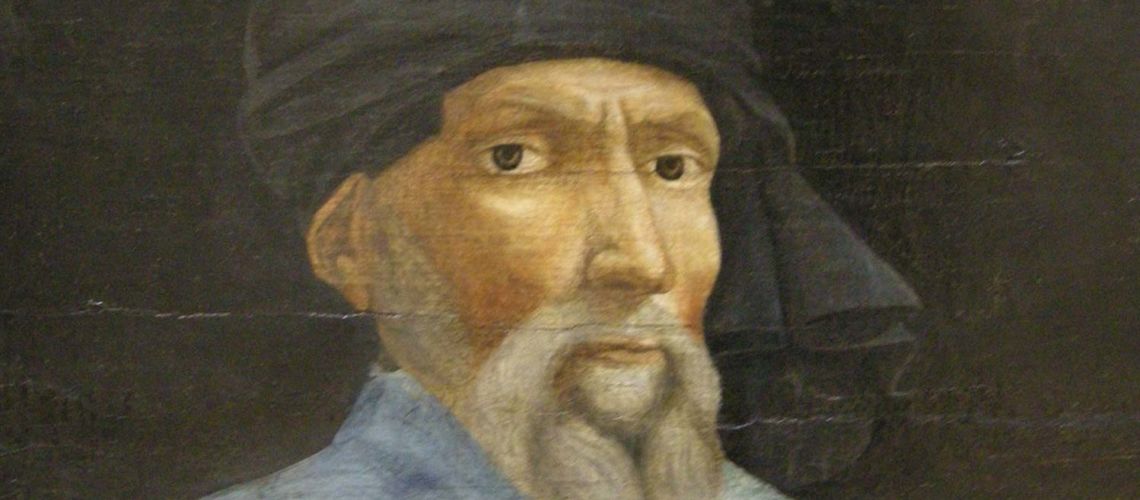

In the Middle Ages Cupid loses its classical form, Christian art and literature move away from that influence of the Hellenistic mystery religions of early Christianity which had allowed the putti to appear, in the classical form, in the harvests of the catacombs and the sarcophagus of Constantine. The erotic image of Cupid becomes unacceptable for the church, which begins to depict it as an emanation of the devil, its appearance loses its joy and becomes sinister: no longer a child but transformed in the 14th century into a devilish animal-legged; we see him in this guise in the fresco of Giotto in the Basilica of Assisi (1325) in which appears with the writing his name “Amor”.

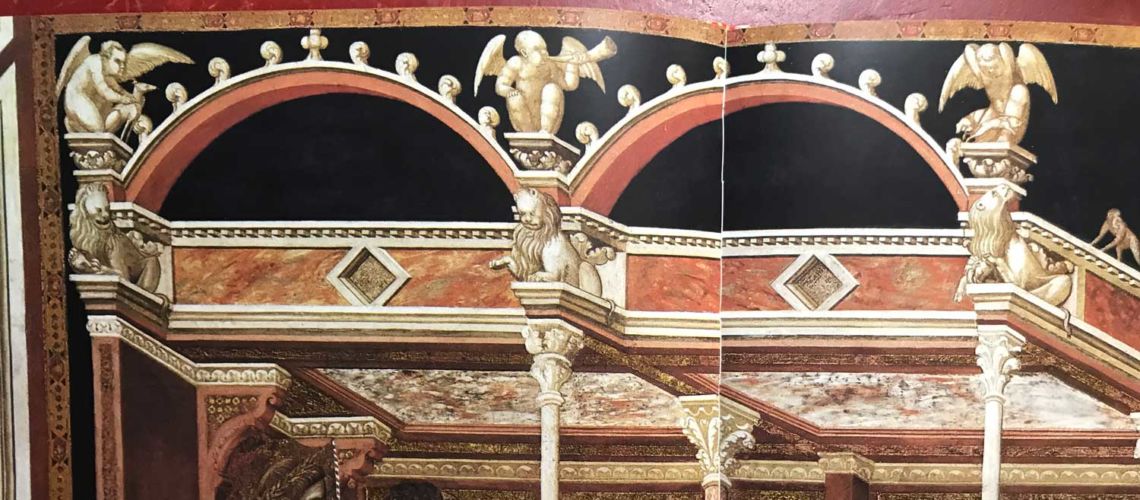

His assistant Pietro Lorenzetti, in the Last Supper and in the Flagellation of Christ, paints at the top some winged monochrome putti with a sinister appearance that they hold strange animals and objects (rabbit, fish, cornucopias).

In the façade of the Romanesque Cathedral of Modena, in 1170 Maestro Wiligelmus sculpted a cupid in forms that were no longer classical, with his legs crossed and leaning on the upside-down torch, and was accompanied by an ibis, a negative bird in that he represented in the medieval bestiaries the “carnal man”.

In the Courteus novels and poems of the Troubadours Eros-Cupid disappears: in the Breton Cycle novels (mid-13th century) the author Cretien de Troyes describes the arrows of love from which his characters are struck, but the archer-eros is never see. But finally in the fourteenth century love also began to be considered a positive force, Dante with Beatrice, Petrarca with Laura; Dante, in the Vita Nova writes that love is not a divinity, but a passion of the human mind.