THE BYZANTINE BRONZE DOOR OF SAN PAOLO FUORI LE MURA IN ROME

This door is part of the group of bronze doors made in Constantinople and sent to Italy, recognizable by the particular style of the damascening designs on the panels, of Byzantine type but slightly Westernized.

Just a few years after 1054, the year of the schism between the Eastern and Western churches, in 1070 the door for the Church of Saint Paul Outside the Walls was cast in Constantinople and immediately shipped to Rome.

It was donated by Pantaleone of Amalfi, “Consul Malfigenus,” as the dedicatory inscription on the door read. Pantaleone, a very wealthy merchant from the flourishing colony of Amalfi in Constantinople,

donated it to the Basilica of Saint Paul in Rome, just as he had donated it to the church of Amalfi, the Basilica of Montecassino, and the sanctuary of Monte Sant’Angelo.

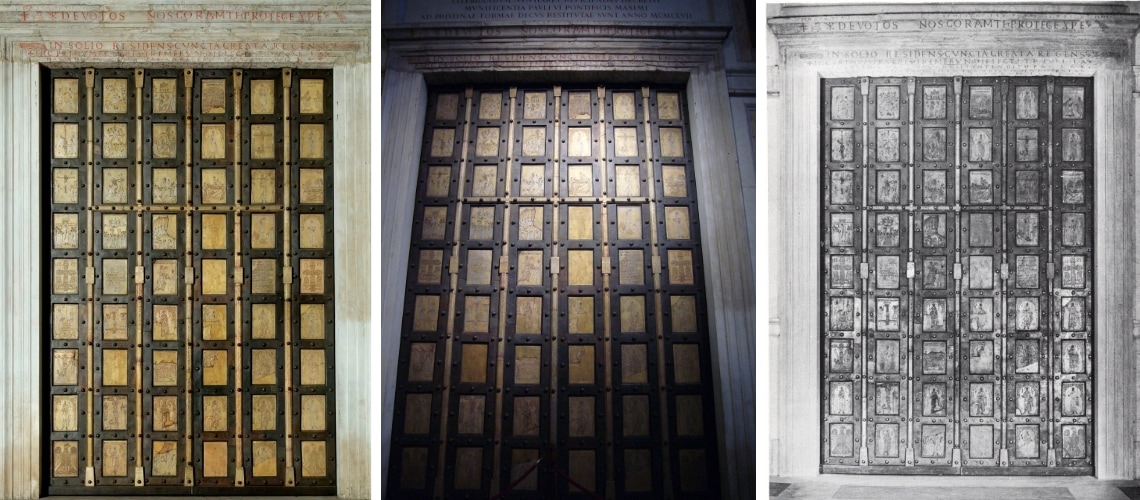

The door we see, although original, is the result of the 1966 restoration, and highlights how in Byzantine bronze doors everything revolved around the design of the intaglios and not the volume of the sculptural parts. No three-dimensional sculpture was required, because the doors had to be

large panels of shiny golden yellow metal “painted” with intaglios, and never patinated; in fact, they were periodically washed to maintain their brilliance (Photos 1, 2, 3).

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

Evidently the schism of 1054 had not interrupted artistic and commercial exchanges between East and West, and had not affected the Roman taste for Byzantine objects; so much so that Hildebrand, the influential figure in the papal circle, requested from Pantaleone Amalfitano, consul in Constantinople, the door in clear Byzantine style.

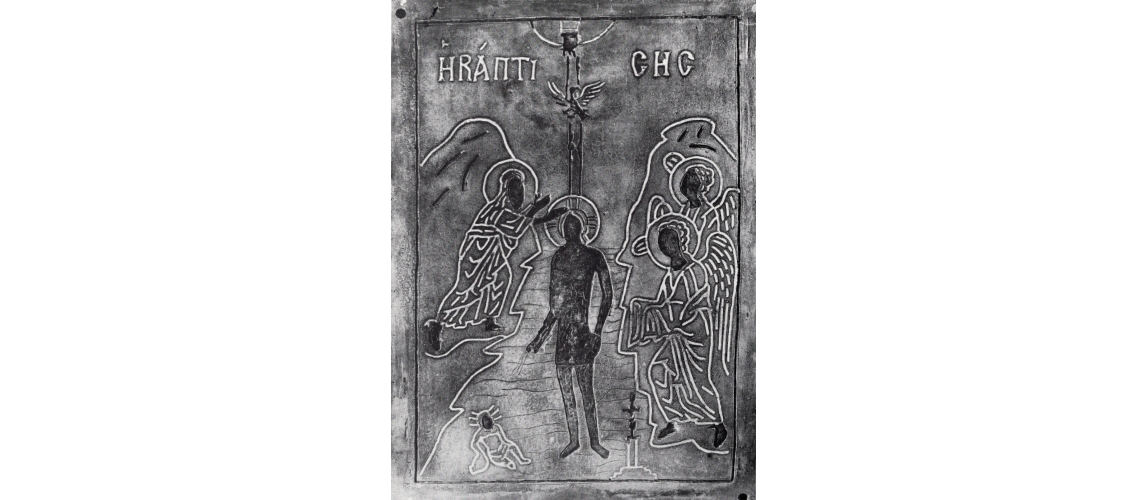

The door (5 meters high and 3.42 meters wide) was composed, like other Byzantine doors, of 54 individual and separate inlaid brass panels, about half a centimeter thick (Photo 4); the panels were fixed to the large wooden door with brass frames nailed to the wood. It was therefore a cladding of metal panels and frames on the wood (Photos 5, 6). These panels were cast using the “stirrup” technique, which is more suitable (and easier and quicker) for obtaining thin, flat sheets than lost-wax casting.

4

| 5 | 6 |

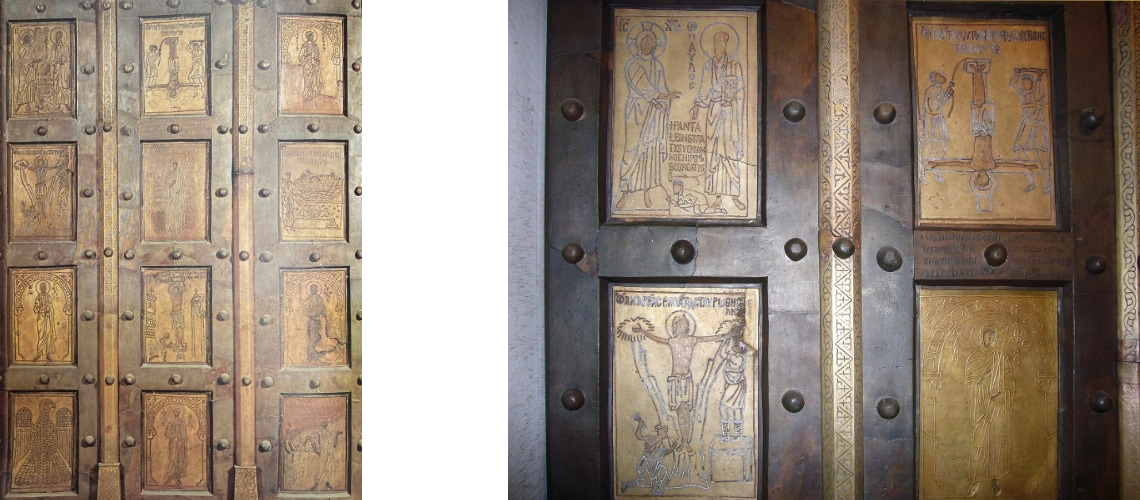

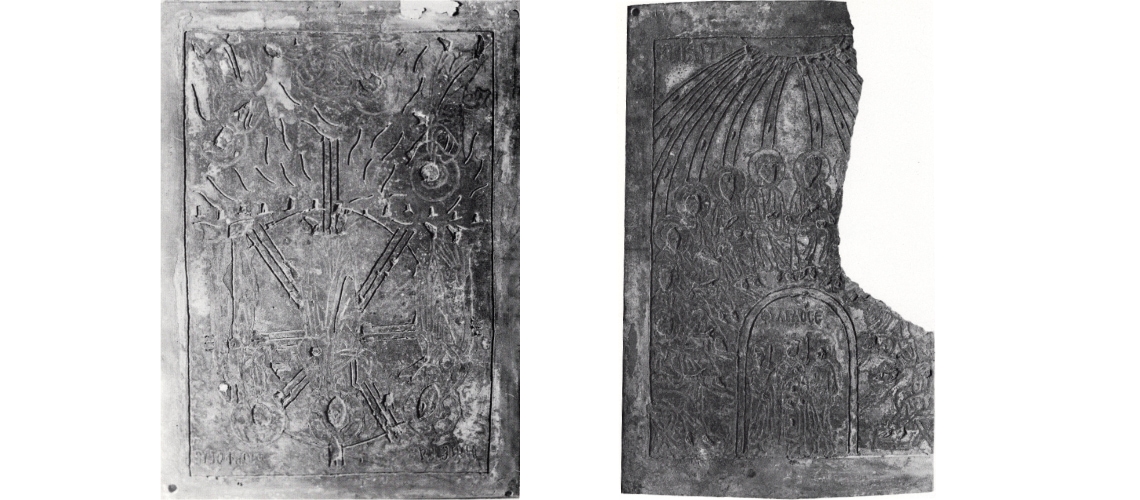

In July 1823, the Basilica of St. Paul suffered a disastrous fire that destroyed much of the building; as many fragments of the bronze door as possible were recovered and stored in a room adjacent to the sacristy. Some of the panels lost the silver originally inserted in the grooves of the damascening (Photos 7, 8, 9, 10).

| 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 |

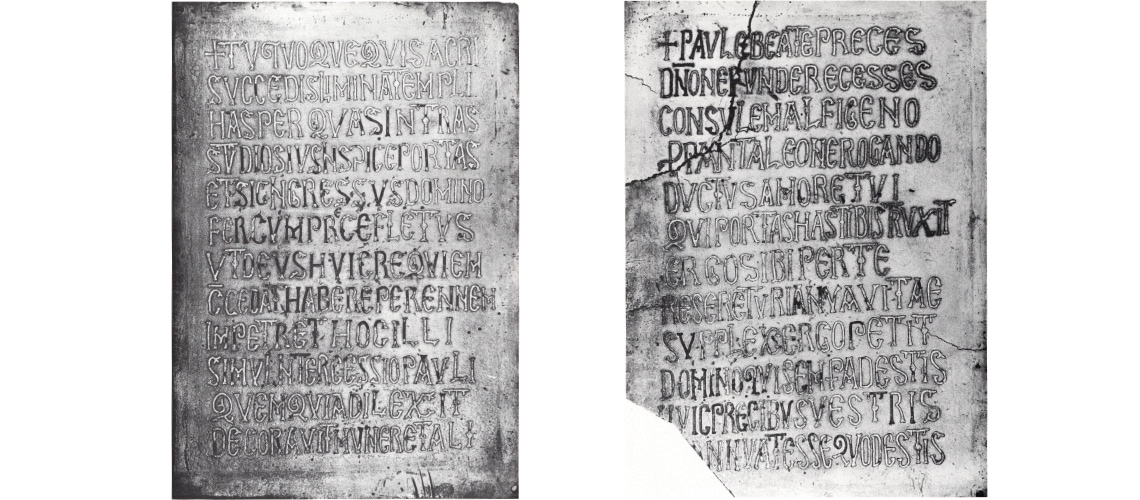

The door featured two inscriptions: one in Greek and Syriac on the frame beneath the Crucifixion of St. Peter, commemorating the founder Staurakios (“It was made by my hand, Staurakios the founder. You who read, pray also for me”), and was lost in the fire at the Basilica (but a faithful copy exists in the 19th-century corpus of drawings by Seroux d’Agincourt); the second appeared during the 1966 restoration and commemorates the artist Theodoros (“O Saints Peter and Paul, help your servant Theodoros who designed these doors”).

An ancient third inscription comes to us from the “Historia delle Stationi di Roma” of 1588 by Pompeo Ugonio (Photo 11), who had seen written on the door itself:

“Anno 1070. Ab incarnatione Domini, temporibus / Domini Alexandri sanctissimi Papae Quarti, et / Domini Ildebrandi venerabilis Monachi et / Archidiaconi, constructae sunt portae istae / in Regia Urbe Costantinopoli adiu / vante Domino Pantaleone Con / sule, qui illa fieri iussit.” which confirmed the construction of the gate in Constantinople in 1070, but this inscription too was lost in the fire of 1823.

11