The Etruscan Chimera

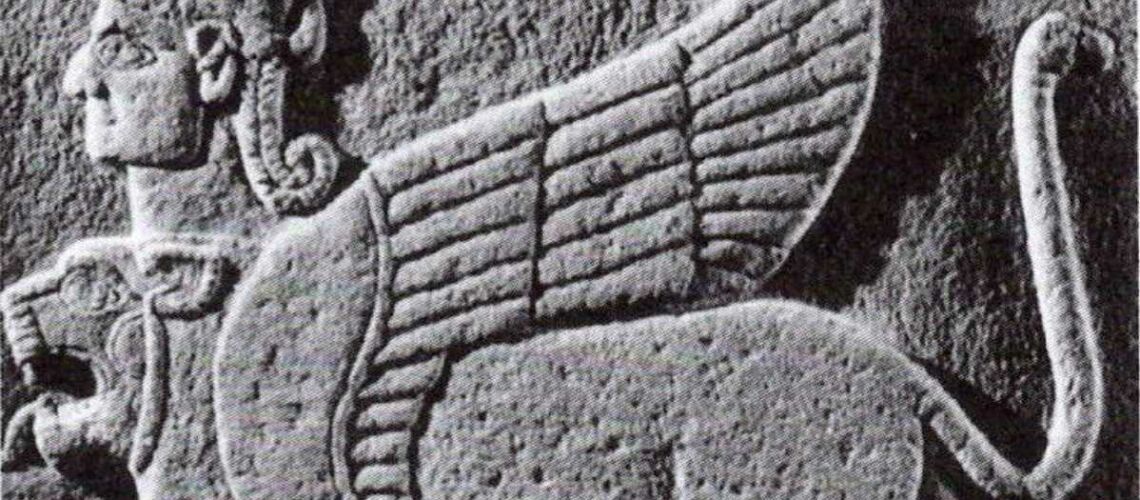

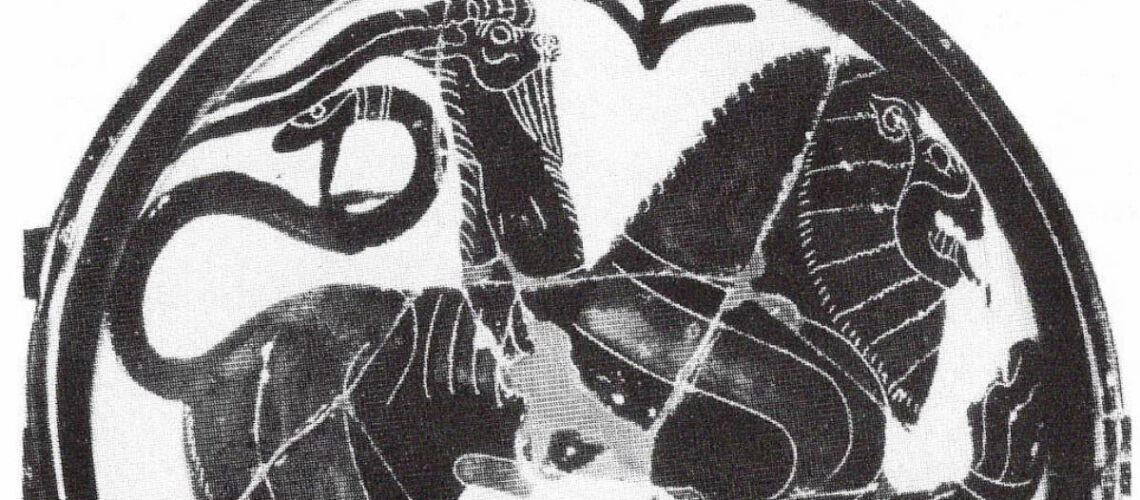

The Chimera, this lion-dog with a snake’s tail and a goat’s head on its back, was formed from the transformation of fantastic animals from Syrian, Persian and Babylonian Assyrian art.

Sphinx-lion, from Karkemish (Turkey), 9th century. BC, Anadolu Medeniyetleri Muzesi, Ankara

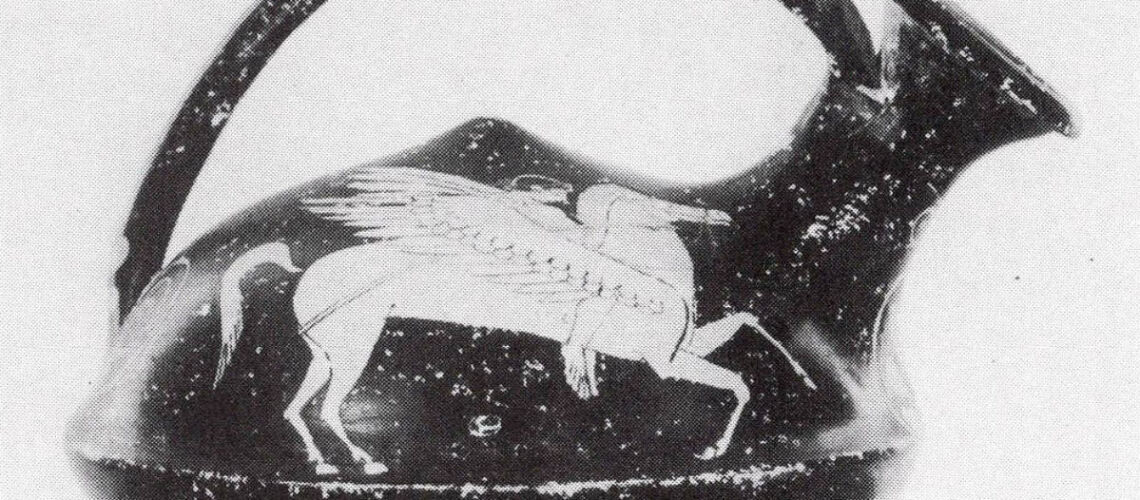

It appeared in the Western world through Greek, Etruscan and Italic art through commercial exchange in the 8th – 7th century BC. The variant in which the goat’s head emerges from a wing is one of the oldest representations.

Bronze relief, San Marciano, 6th century. BC, Antiken Sammlung, Munich

Etruscan amphora from Vulci, 530 BC, Fitz. Museum, Cambridge

But it is at the end of the 5th and beginning of the 4th century BC. that the Chimera with the Etruscan civilization reaches the apex of its artistic representation with the bronze of Arezzo.

Archaeological Museum of Florence

Archaeological Museum of Florence

Archaeological Museum of Florence

Archaeological Museum of Florence

Archaeological Museum of Florence

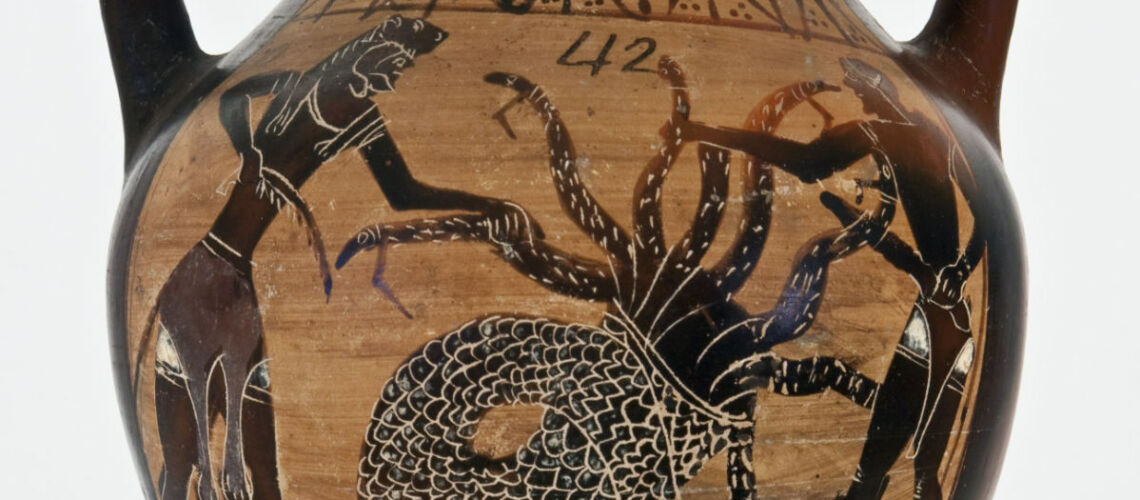

There are various Greek myths relating to his birth: according to Homer it was a divine animal fed by Amisodaros king of Caria; for Hesiod it was the daughter of the Hydra of Lerna and the Nemean lion, granddaughter of Typhon and Echidna, sister of the sphinx. It symbolized chthonic power and of the underworld’s forces.

Attic black-figure amphora with Heracles slaying the Hydra, Princeton Painter, 550-525 BC.

Detail of the Attic black-figure amphora with Heracles slaying the Hydra, Princeton Painter, 550-525 BC.

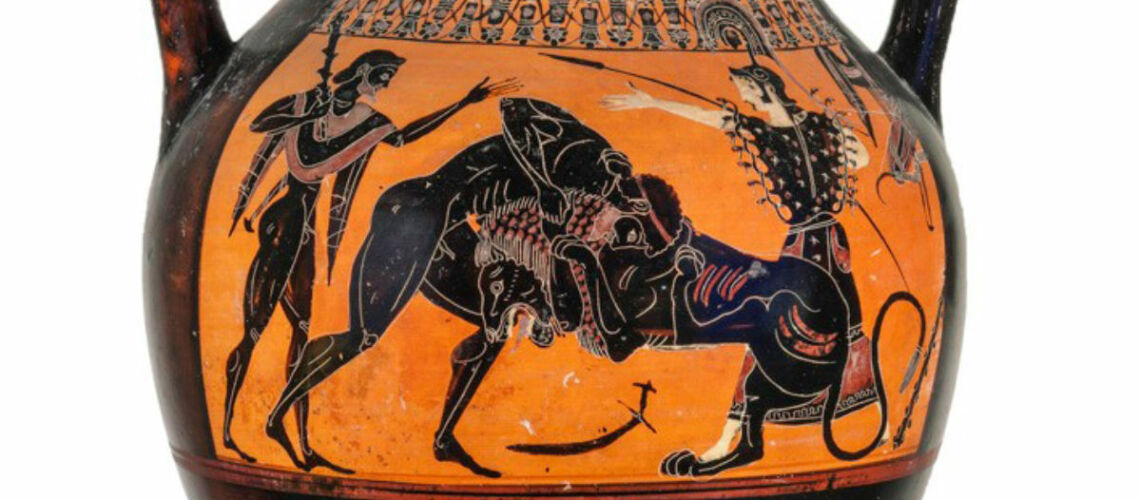

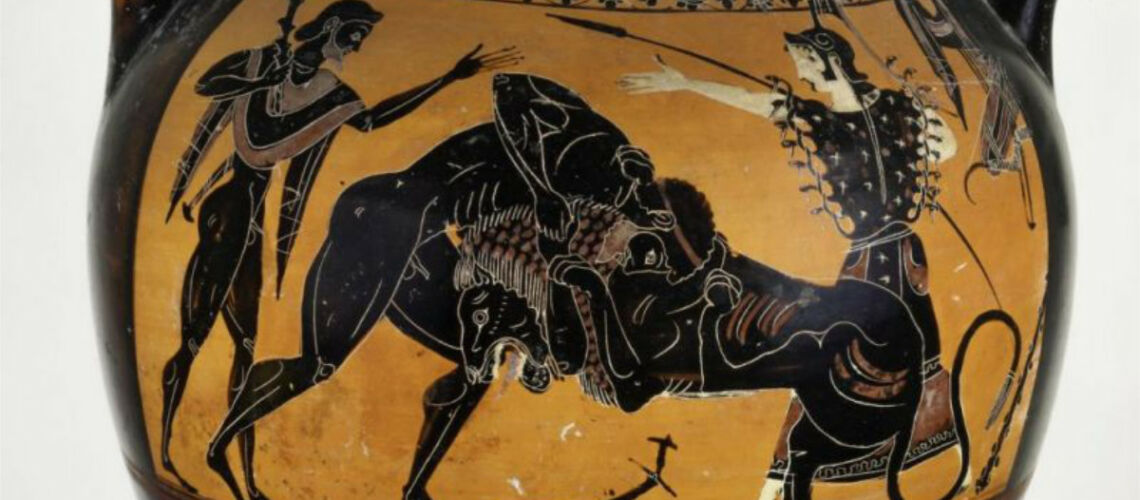

Attic black-figure amphora, Boulogne Painter 520-510 BC, from Cerveteri

Detail from the Attic black-figure amphora, Boulogne Painter 520-510 BC, from Cerveteri

It was killed by the Corinthian hero Bellerophon of the lineage of Sisyphus, son of Eurynome and Glaucus and Poseidon: the myth tells that Bellerophon fled from his homeland for having involuntarily caused the death of his brother and went to Prince Preto in Argos, where, however, he refused the advances of his wife Sthenebea who took revenge by sending him to his father-in-law Lobate king of Lycia, who to expiate him invited him to perform a series of “labours” including that of killing the Chimera, helped by the winged horse Pegasus.

Peter Paul Rubens, Bellerophon, Pegasus and the Chimera, 1635, Musée Bonnat, Bayonne

In Etruscan times the Chimera with Bellerophon was positioned to protect the city gates with an apotropaic function, and the Chimera of Arezzo was found near the ancient Etruscan gate corresponding to the current Porta San Laurentino;

It is probable that some representations of angels or saints with the same function of guardians of the doors derive from the memory of the ancient mythical episode, such as San Michele or San Giorgio often depicted with wings like Pegasus, the winged horse of Bellerophon, which they are about to kill the dragon, a distant relative of the Chimera.

Botticini, on the left the Archangel Michael, ca 1471, Uffizi

Raphael, S. Michele, 1505, Louvre

Walls of Florence last circle, Porta S. Giorgio

Walls of Florence last circle, Porta S. Giorgio, detail of the bas-relief

At the beginning of the seventh century BC. C. the Chimera was still implemented in a purely decorative way, and at the end of the sixth century BC. its image began to appear on coins, gems, beetles, antefixes,

Silver stater, Sicyon, 4th century. B.C.

Corinth 430-405 BC

Intaglio onyx with a blue layer on a black background, 1st cent. B.C.

Clay antefix from Thasos, 550 BC, Mus. National, Athens

on ceramics,

Corinthian aryballos from Camirtos, Painter of heraldic lions, last quarter of the 3rd century. B.C., Victoria and Albert Mus., London

Laconic kylix, Painter of the Chimera, Third quarter of the 6th century. BC, Heidelberg, Mus. of the University

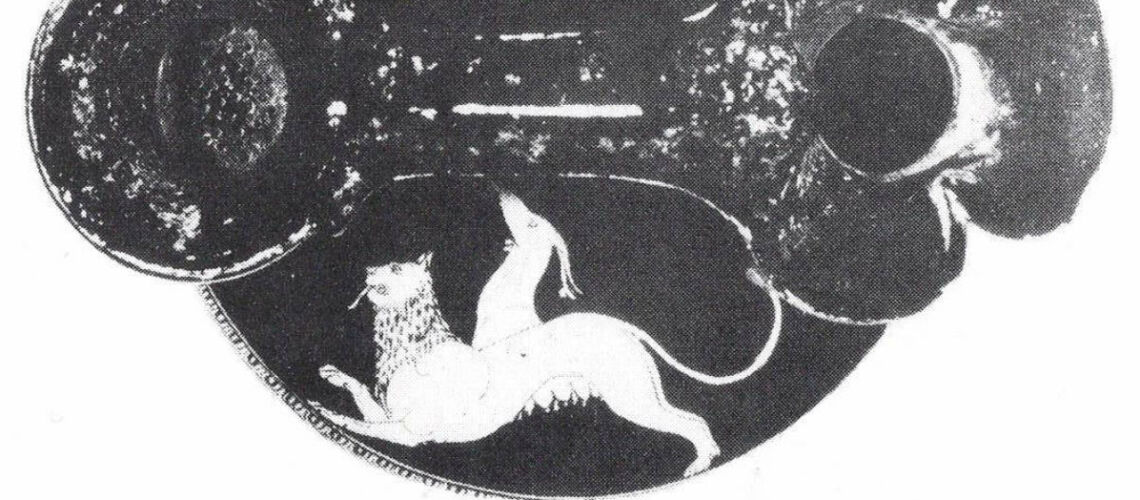

Apulian red-figure plate 350 BC

In the 5th century BC. there was the return and diffusion of the myth of it with Bellerophon on Pegasus who kills it which continued even in Roman times appearing on ceramics, mosaics, frescoes, gems and coins.

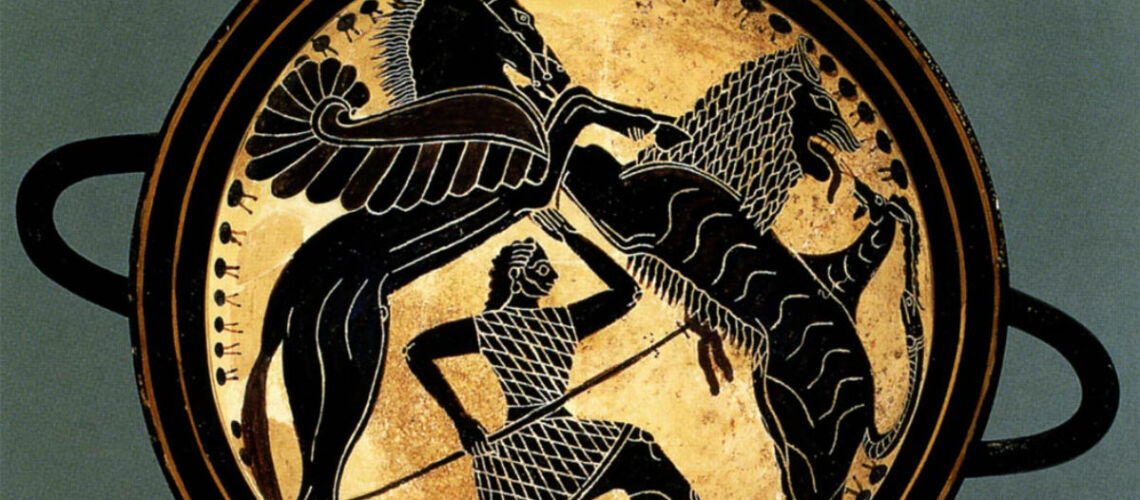

Laconian black-figure kylix Boread Painter Getty Villa, Malibu 570-565 BC

Attic red-figure pottery 420 BC

Apulian dish

Attic red-figure askos. Last quarter of the 5th century BC, Louvre, seen from above

Attic red-figure askos. Last quarter of the 5th century BC

Attic red-figure askos. Last quarter of the 5th century BC

Mosaic, Rhodes, 300-270 BC.

La-Chimera-Roman-mosaic-Musee Rolin Burgundy France

Roman fresco with Cupid, Pegasus, Chimera, I-II century. AD, Cologne, Museum

Intaglio onyx with a blue layer on a black background, 3rd century. AC

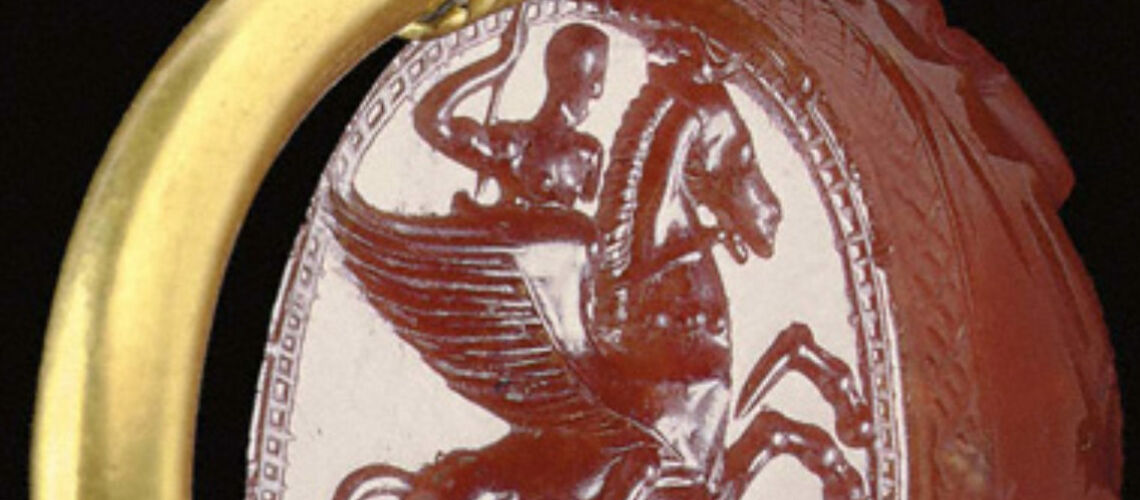

Etruscan scarab ring, ca. 400 BC Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University

Didrachmus of the Fenserni (Campania) 390 BC, Berlin

Corinth, bronze, Augustan age

The Chimera of Arezzo is male (although in ancient times the Chimera also appeared in female forms) and is represented wounded by enemy blows on the left thigh and on the neck of the goat’s head hanging on the left side now dying .

Lanceolate socket on left hip

Lanceolate cavity on the neck of the goat’s head

The animal’s body has been modeled with plastic naturalism, while the head still has a strong archaic flavor as a sculptural work of transition between two artistic styles.

Archaeological Museum of Florence

Archaeological Museum of Florence

Archaeological Museum of Florence

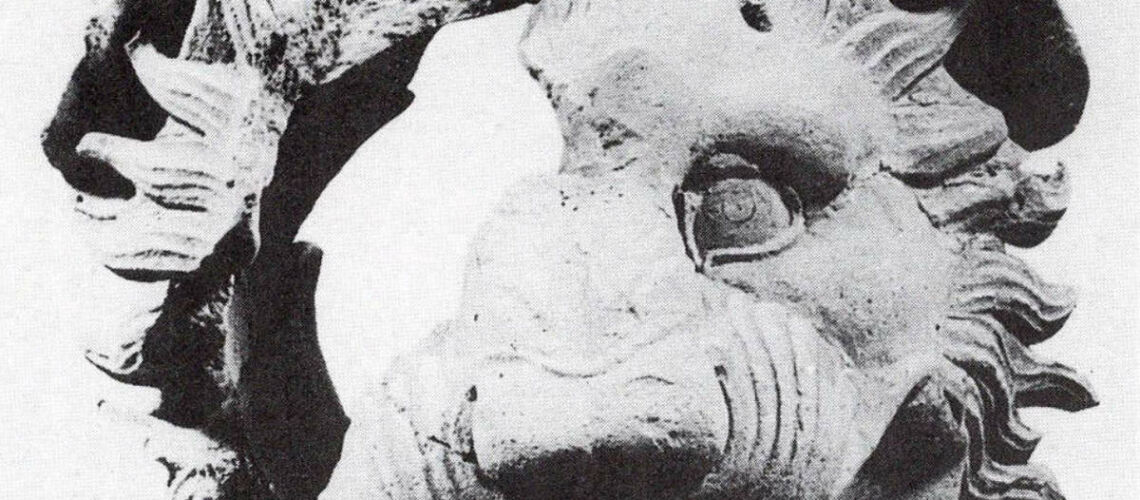

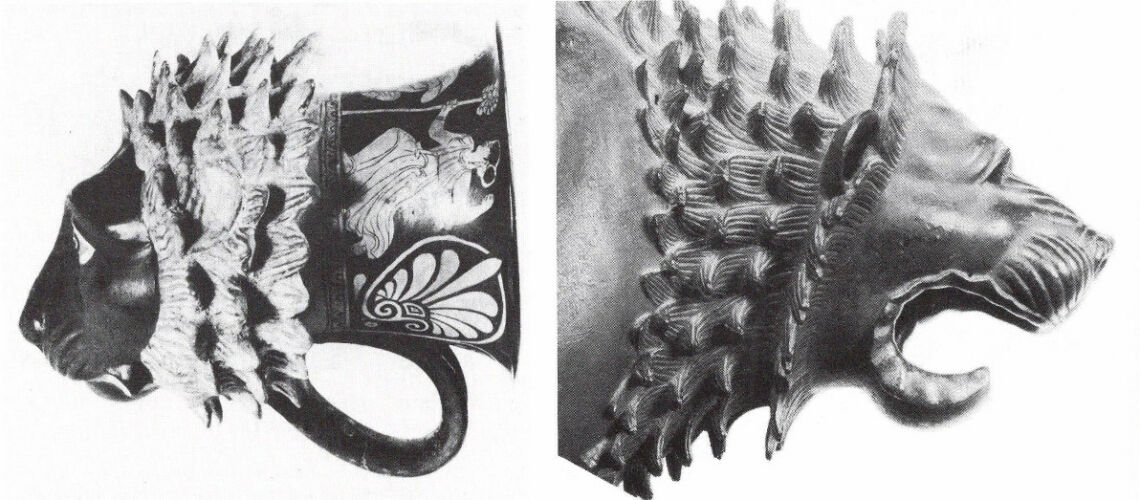

Particularly convincing on the archaic nature of the head is the comparison with the clay drip from Metapontum dating back to the mid-5th century BC. and the red-figured Attic Rhyton of Ruvo from the end of the 5th century. B.C.

Clay drip from Metapontum

Chimera of Arezzo, detail

|

Attic rhyton with red figures, Ruvo, end of the 5th century. B.C. |

Detail of the Etruscan Chimera |

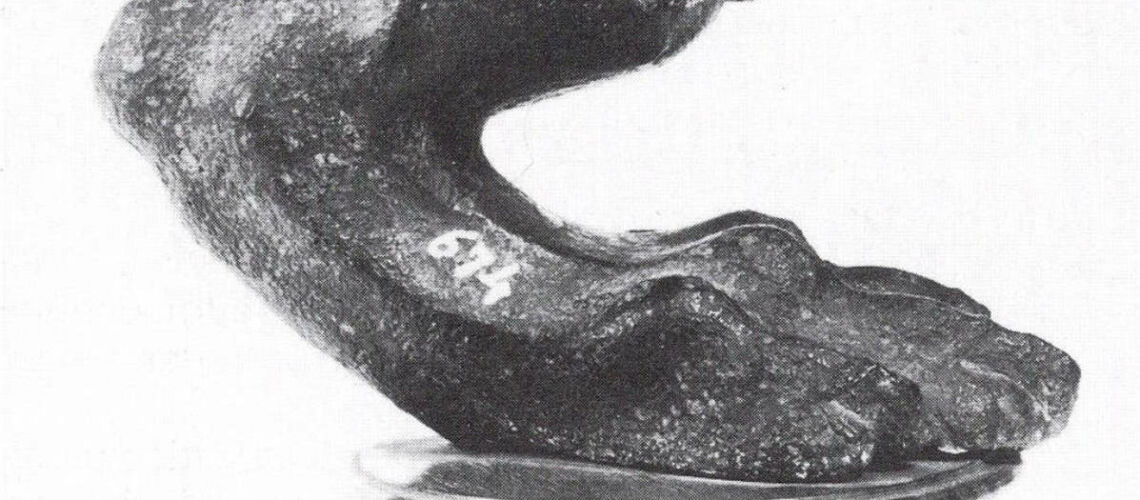

Other stylistic affinities can be found in the comparison with the funerary statue from Marciano in the Antikensamlung in Berlin and with the support paw in the Archaeological Museum in Florence.

Cinerary statue from Marciano, Antikensammlung, Berlin

Bronze support with feral paw, Mus. Archaeological, Florence

The study of the Etruscan writing on the left leg tinscvil, engraved on the wax before casting, confirms the dating of the Chimera of Arezzo at the end of the 5th – beginning of the 4th century. B.C.

Chimera, detail

The myth of its killing foresees that the Chimera and the other two figures of Bellerophon and Pegasus are united in a single sculptural group, as often happens. But the Chimera, like other monstrous figures, is also represented by itself, i.e. she takes on an autonomous life as precisely in coins, ceramics, etc.

The Chimera of Arezzo may have been removed from a bronze group with Bellerophon riding Pegasus. However, the Etruscan dedication written on the left leg of the animal engraved on the wax before casting could also suggest a single casting. The bronze would then be buried together with other small bronzes in a votive deposit.

The sculpture is about 80 cm high and about 130 long including the tail, which however is not in its original position due to the eighteenth-century restoration.

Cosimo I dei Medici Duke of Tuscany ordered that both the Chimera and the other finds excavated in Arezzo be brought to him, and exhibited the large bronze in the rooms of Pope Medici Leo X in Palazzo Vecchio, as a symbol of all the fairs he won in the creation of the Kingdom of Etruria. Subsequently it was taken to the “midday corridor” of the Uffizi. Today it is in the Archaeological Museum of Florence.

The restoration was done by Cellini; the legs on the left side, found detached from the body just above the joint, were roughly reattached with lead casting.

Left front paw outside

Inner side left front paw

Left hind leg outer side

Left hind leg inside

In 1785 the sculptor Carradori recreated the tail of the animal (still not remade in the drawing of Verkruys Drawing of 1724 reproduced by Th. Dempster in 1720-1726)

Verkruys drawing from 1724 reproduced by Th. Dempster, De Etruria regali libri septem, Florence, 1723–1724

not respecting the original trend, only the part closest to the body of the Chimera is a fragment of the original tail and the position of the snake biting the horn of the goat’s head was created to give it a foothold thanks to which to support its weight .

Junction between the original section of the tail with the part rebuilt in the 18th century

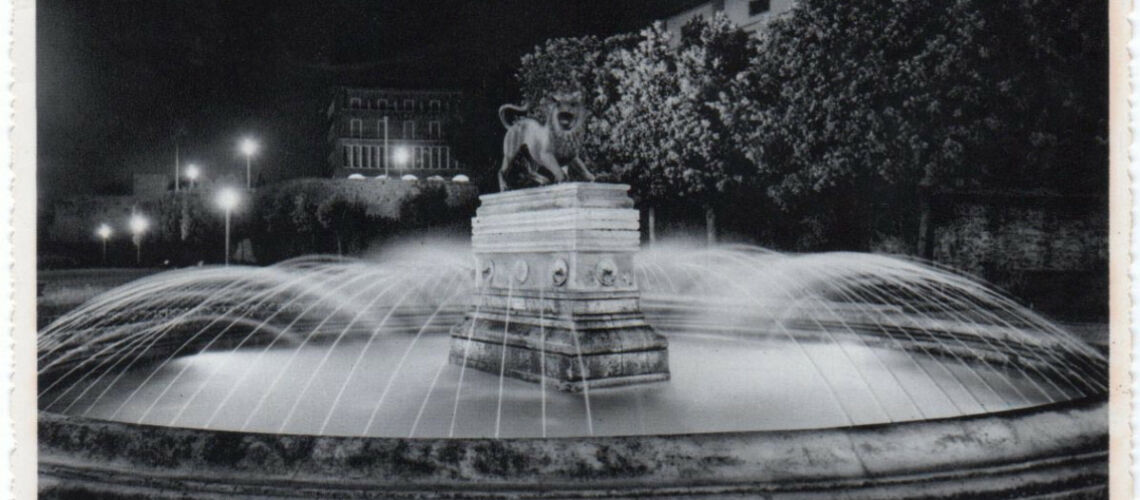

In 1933, in front of the Arezzo railway station, two fountains were placed with a replica of the Etruscan Chimera cast by the Aglietti foundry in the center of each one. During the Second World War they were removed and the metal melted down for military purposes.

After the war, the Municipality of Arezzo asked the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry of Florence to cast two replicas which were repositioned in place of the lost ones.

Fountain with the twentieth century copy of the Chimera on the right side of the gardens of the Arezzo station

Fountain with the twentieth century copy of the Chimera on the right side of the gardens of the Arezzo station

The twentieth-century copy of the Chimera on the right side of the gardens of the Arezzo station

Several times this magnificent bronze conserved in the Archaeological Museum of Florence has been requested to be exhibited both in exhibitions and museums in various parts of the world have set up. And a serious problem arose: if the original is lost during transport by ship or by plane, how can it be done? Losing such a masterpiece would be a tragedy and a crime. The project of the “identicals” was therefore born by the Archaeological Superintendence, that is, the creation of absolutely identical replicas of these bronzes, to be sent to the various exhibitions and keep the original in the Museum.

The management of the Archaeological Museum of Florence therefore contacted the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry through the Bazzanti Gallery, to begin studying the possibility of performing a negative cast not only on the Etruscan Chimera, but also on two other Etruscan bronzes in the Museum: the Etruscan Minerva , and the Idolino, to then cast the identical ones in lost-wax bronze. Having ascertained the capacity and working quality of the foundry, he proceeded to give it the assignment.

Our technicians have reached the laboratories of the Archaeological Superintendency and have begun to execute, with extreme care, the mold of the Chimera in silicone rubber and mother mold in plaster.

Realization of the mould on the original Chimera

Realization of the mould on the original Chimera

From the mould, carefully transported to the foundry, the waxes to which the castings were applied were made and retouched, the casting performed and processed, the parts assembled and welded.

Mother mold in silicone rubber

Snake wax retouch

Retouched head wax

Application of castings to the head wax

The wrought bronze is reassembled

The “identical” of the Chimera was exhibited at the Florentine Archaeological Museum, and was then sent to various exhibitions such as the 2014 “Etruscan Seduction. From the secrets of Holkham Hall to the wonders of the British Museum” at Palazzo Casali in Cortona.

It is currently located at the entrance to the Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Ferdinando Marinelli Jr. presents the “Identico” at the Archaeological Museum of Florence