Verrocchio and his David

David in the Middle Ages

The figure of the biblical David has fascinated the Florentines in a particular way since the Middle Ages. In the Old Testament he is described very well, better than most other prophets have been. Among the peculiar characteristics of him at the moment in which he kills the giant Goliath six cubits and a palm tall is his young age, so much so that he cannot yet be part of the army, his lack of physical prowess, his intelligence that wins over brute force. He is not a saint, on the contrary he has the vices of men when he takes Bathsheba as wife of Uriah whom he then kills, he has corrupt and delinquent illegitimate children, except the wise Solomon. He defeats the Philistines allowing the birth of the Kingdom of Israel.

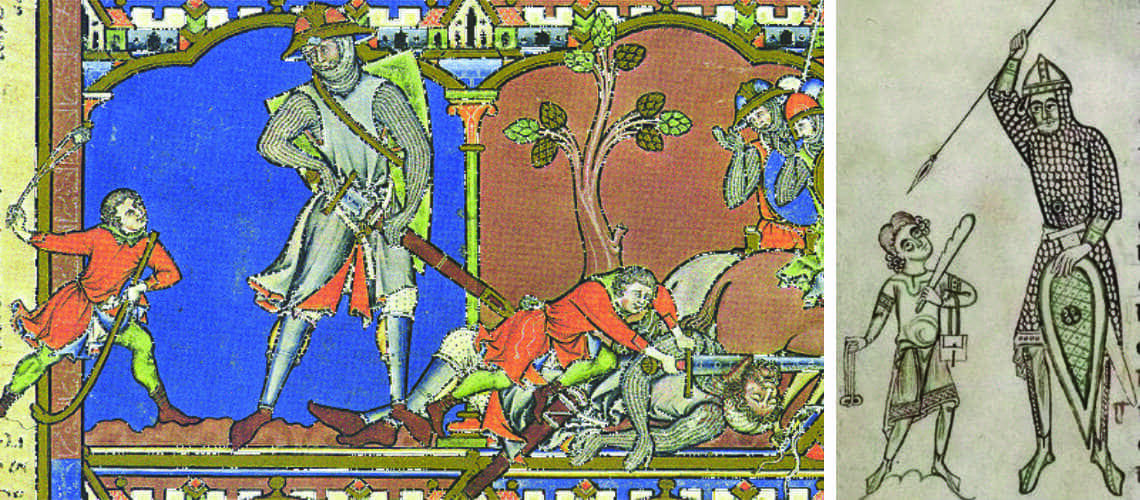

The David in miniatures

In the miniatures that decorate the medieval Bibles he is represented precisely as a young man with a slingshot that attacks and kills Goliath.

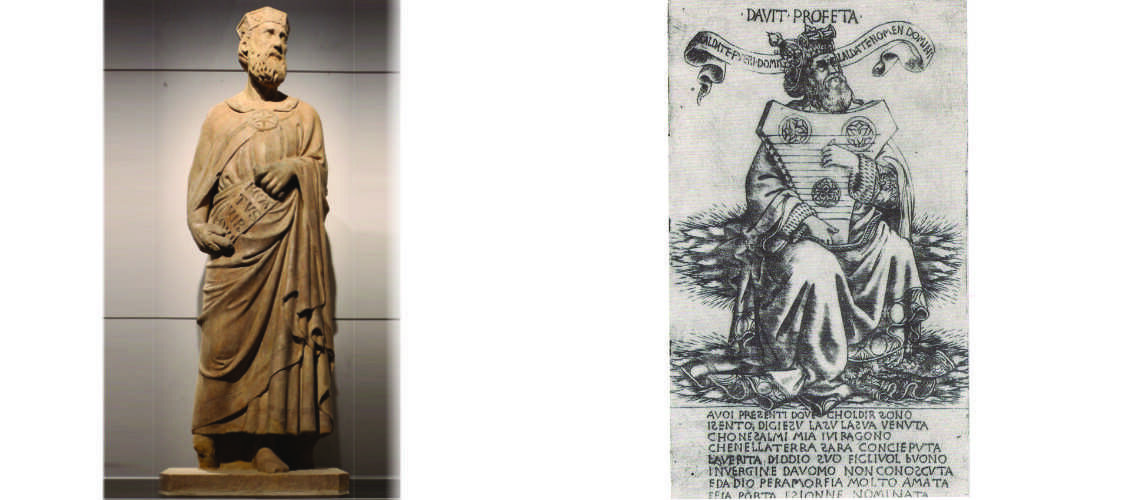

David as prophet

In the fourteenth century, in the bell tower of the Florence Cathedral, Andrea Pisano represented him as a prophet and king, not young but bearded, without slingshot or sword and without allusions to Goliath and his killing.

Even at the beginning of the Renaissance he is represented as an old bearded man who plays the zither, associating him with music.

| Andrea Pisano, David, c. 1340, Museo Opera del Duomo, Florence | Florentine school engraving, mid-15th century, British Museum, London |

David rejuvenates

But around 1330 in Florence in the fresco by Taddeo Gaddi, David appears for the first time young and beardless, in a short tunic, with the decapitated body of Goliath at his feet, and in his hand he holds the severed head of the slain Giant; in his other hand he has the sword with which he cut off his head and from his belt dangles the sling with a stone. This iconography in Florence will no longer be abandoned in Renaissance sculptures.

Taddeo Gaddi, 1330, Baroncelli Chapel, S. Croce, Florence

The David symbol of the Florentine Republic

When Donatello sculpted the Marble David in 1409, a young man with the head of Goliath and a slingshot at his feet, he wanted to represent a clear response to the attacks on Florentine freedom: the Milanese tyrant Giangaleazzo Visconti was about to conquer Florence when he suddenly died.

In 1416 the statue was purchased by the Signoria of the Republic of Florence which brought it to Palazzo Vecchio. David becomes the defender of freedom and a symbol of divine help against enemies.

It was a very important step: David leaves the ecclesiastical sphere for the first time to become a civil hero. And when in 1390 the interior of Orsanmichele was frescoed at the expense of the Arts, David was again with his head uncovered, wearing a short tunic and a short cloak.

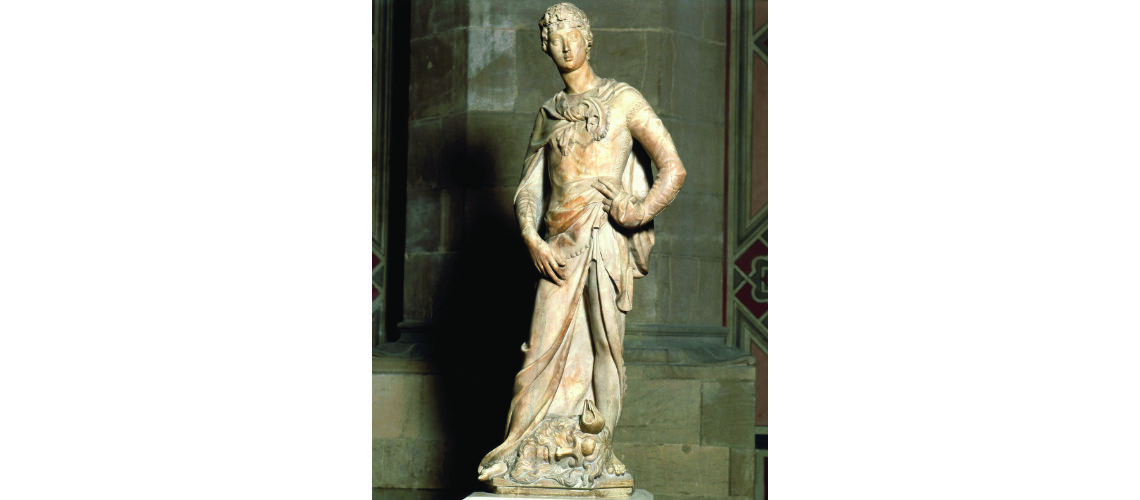

Donatello, David in marble, 1409, Bargello

The David for the Medici family

Donatello created a second David for the Medici cast in lost wax bronze, wanted to underline their great patriotism against any form of dictatorship. This time Donatello modeled him completely naked except for the shoes and the hat, a highly sensual figure, a sensuality that in a few years had been accepted and admired so much as to become a symbol, even if only civil, of youth and heroism.

Donatello, David in bronze, 1440, Bargello

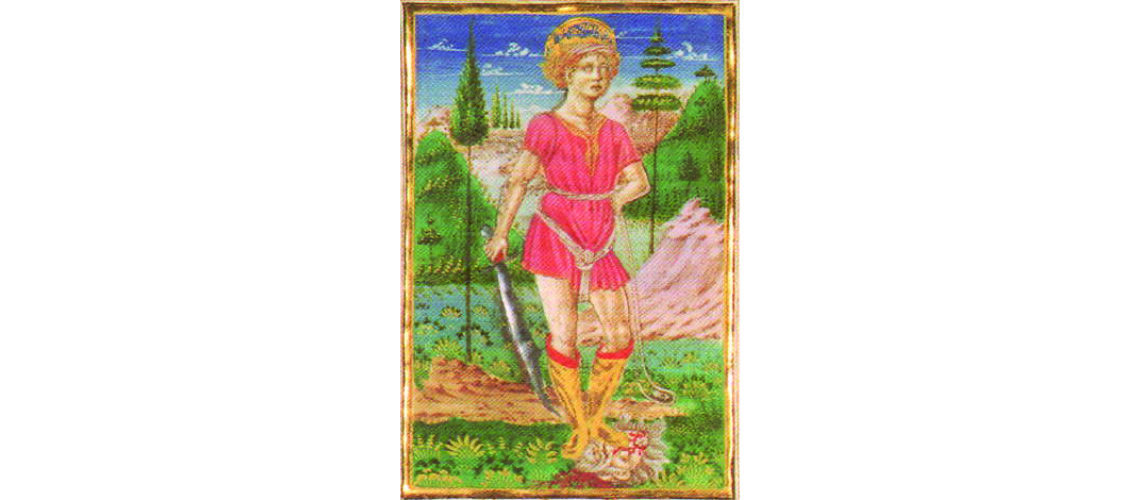

The censored David

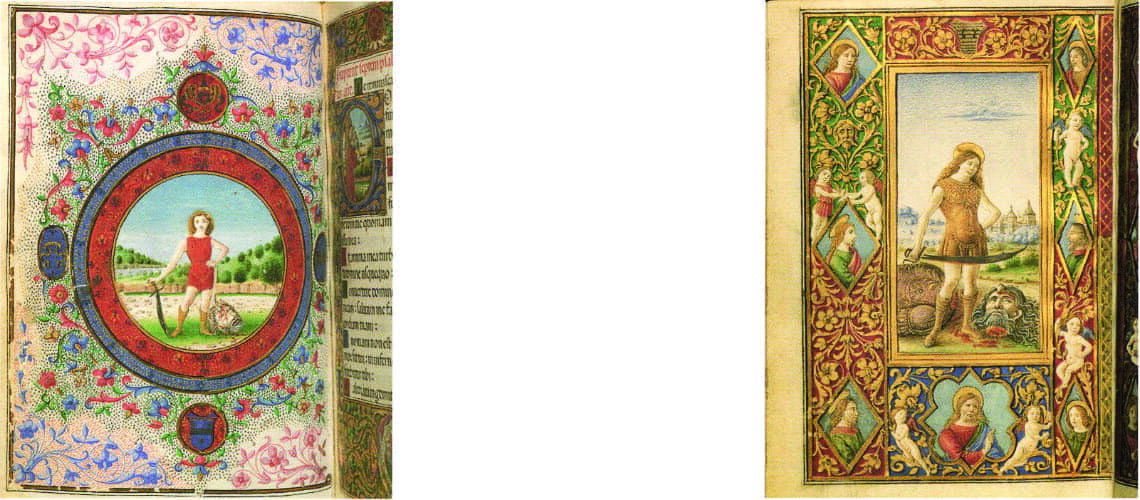

However, especially in the religious sphere, David’s total nudity was partially censored, as in a miniature by Mariano del Buono from the late 1460s in a manuscript with psalms for Piero dei Medici: “he has a short dress that covers nudity but leaves his sensual legs visible, a belt hanging in front of his genitals, a sling in his left hand, a sword in his right, at his feet the bleeding head of Goliath”.

Mariano del Buono, miniature end of about 1460, Laurentian Library

Il David nella Porta del Paradiso

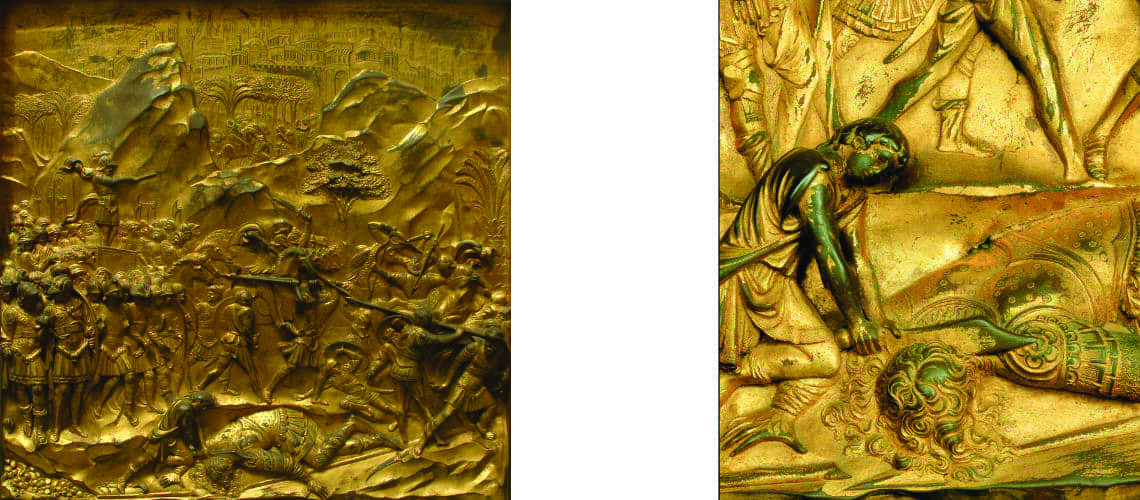

In the David panel of Ghiberti’s Gate of Paradise finished in 1452, in the center of the scene, below, David appears beheading the giant Goliath who was killed on the ground. He is also this young man and without a hat, he has the same shoes, but he is dressed.

| Ghiberti, Door of Paradise Panel “David”, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence | Detail |

The David as decoration

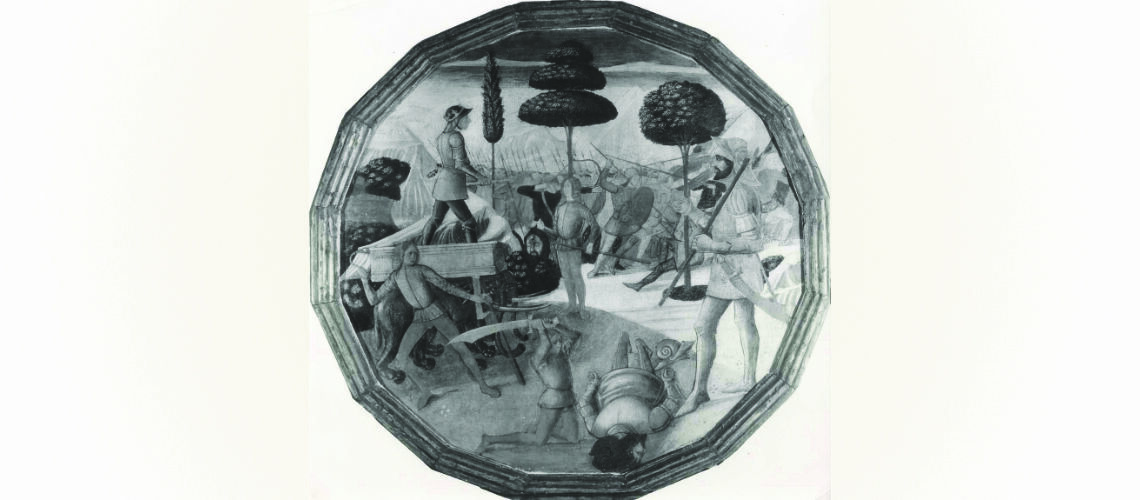

From the second half of the 15th century the scene of David killing Goliath appears on chests, birth trays and other artefacts, in some cases he is fully clothed, in others he has only his legs uncovered. On a desco da parto (c. 1480) he is kneeling as he is about to decapitate the giant; on the first wedding chest (c. 1460) three moments are described: David with bare legs, short dress, shoes and cloak collects stones to throw with a slingshot; then David who is about to throw the stone with a sling against the giant Goliath; and in the center of the chest David beheads Goliath with the sword.

On the second chest David is triumphant in a chariot holding Goliath’s head by the hair.

Desco da Parto, anonymous Florentine, c. 1470, Loyola University, Chicago

Francesco Pesellino, Wedding Chest with David and Goliath

Wedding Chest with Triumph of David, ca. 1460, National Gallery, London

In a parade shield painted by Andrea del Castagno around 1455. David is haired, dressed but with bare legs and holds the sling, and between his legs has the head of Goliath.

Andrea del Castagno, parade shield, ca. 1455, National Gallery of Art, Washington

David’s images on artifacts of this type also tend to take on different meanings, such as courage and the valor of youth

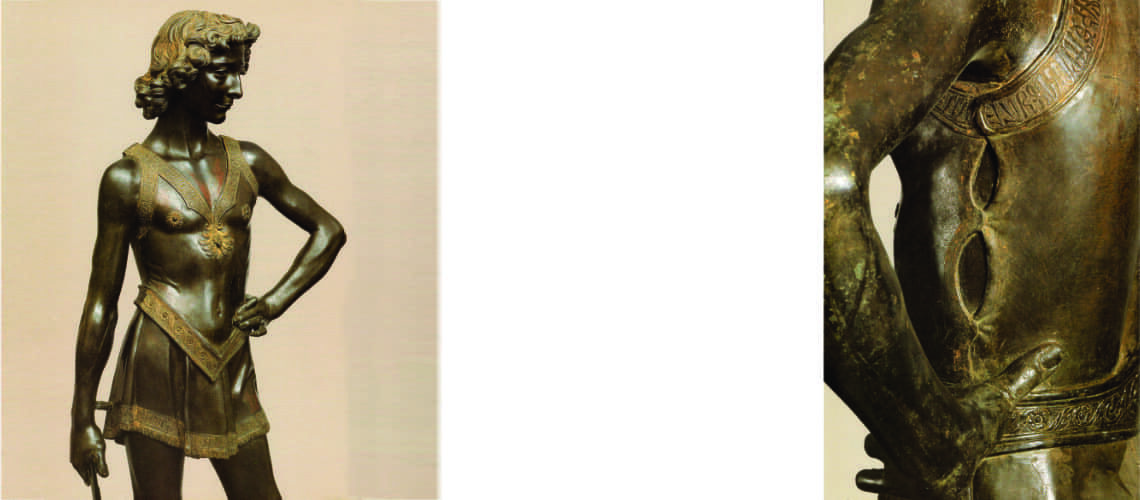

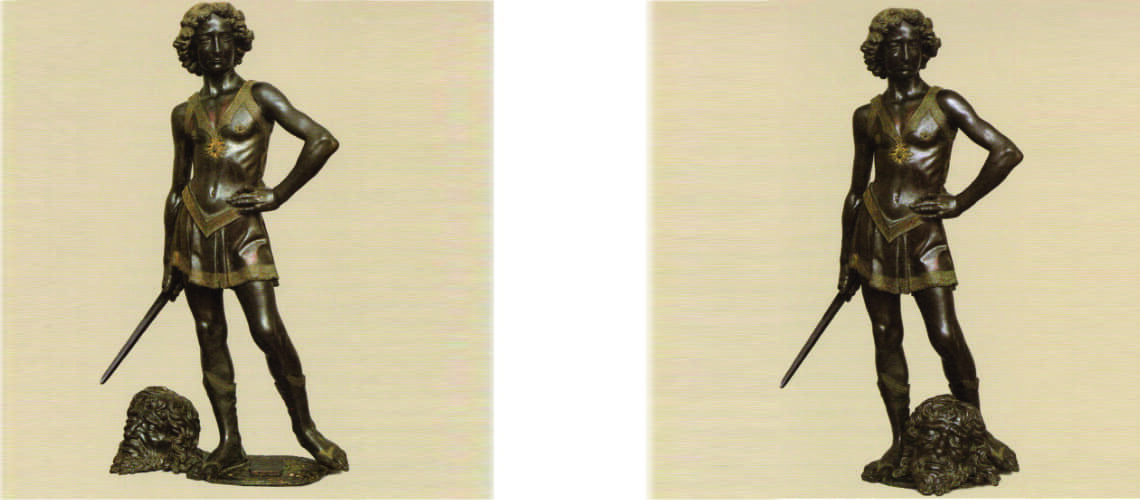

Verrocchio's bronze David

Around 1475 Andrea del Verrocchio models and casts one of his Davids in lost wax bronze. It is natural that he looks at the elegant and admired bronze David created by Donatello. And he resumes the pose: the left arm bent and resting at his side, with the sword in the right hand, the weight of the body resting on the right leg and the left leg slightly bent. The novelty of the sculpture is the dynamism and the sense of life that Verrocchio manages to give to his David also using the sword that is kept filling the space away from the body.

His David is very young, his bare head has allowed the sculptor to give him a thick mane of hair, his mouth hints at a very slight smile of satisfaction, satisfaction also present in his gaze. Compared to Donatello’s hero, Verrocchio’s David is sunny, shrewd, more direct and certain.

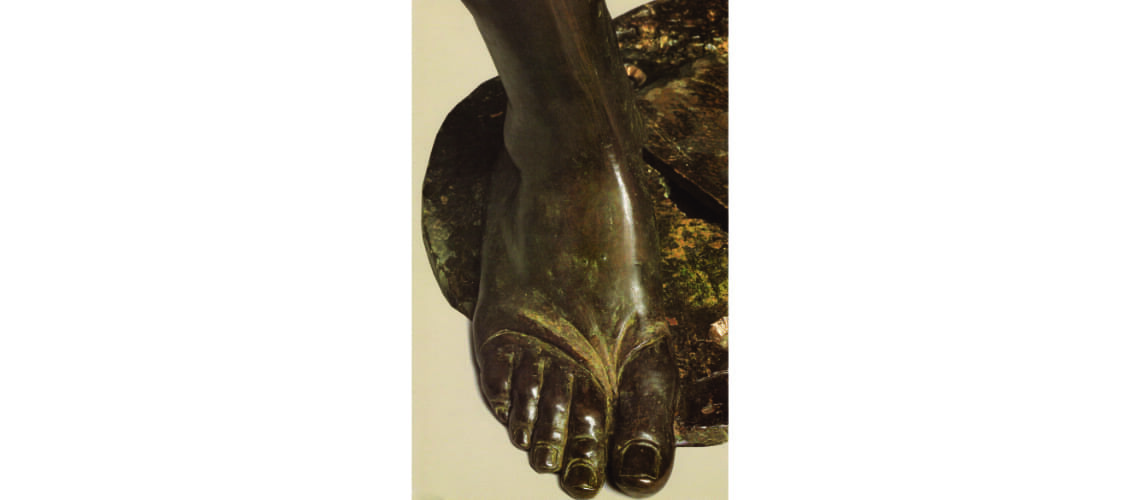

He is not naked, but is clad in a thin (leather?) armor that perfectly follows his features and leaves his legs bare; he is no longer a shepherd in fact he wears a military-style robe and

the shoes are lower and less rich than those of Donatello.

Verrocchio modeled the head of Goliath so that it could be cast separately from the statue of David. In fact, it is probable that initially he had wanted to place it not between David’s legs but laterally to his right. In some manuscript miniatures, deriving from this David having the same type of armor that covers him, the head of the Goliath is placed to the side, something never happened before; in particular in the miniature of Mariano del Buono of 1465-1470 and that of Attavante of 1470-1480.

| Mariano del Buono, miniature with David, ca. 1464-1470, Victoria and Albert Museum | Attavante, miniature with David and Goliath, c. 1470-1480, Zamek Krolewski, Warsaw |

The David on one of the wedding chests

And again in the wedding chest of the Master of Stratonice from around 1470 the sculpture of David on the high base has the head of Goliath on the left side.

| Master of Stratonice, Marriage of Stratonice, c. 1470, Huntington Library, San Marino, California | Master of Stratonice, Marriage of Stratonice, detail |

La testa di Golia

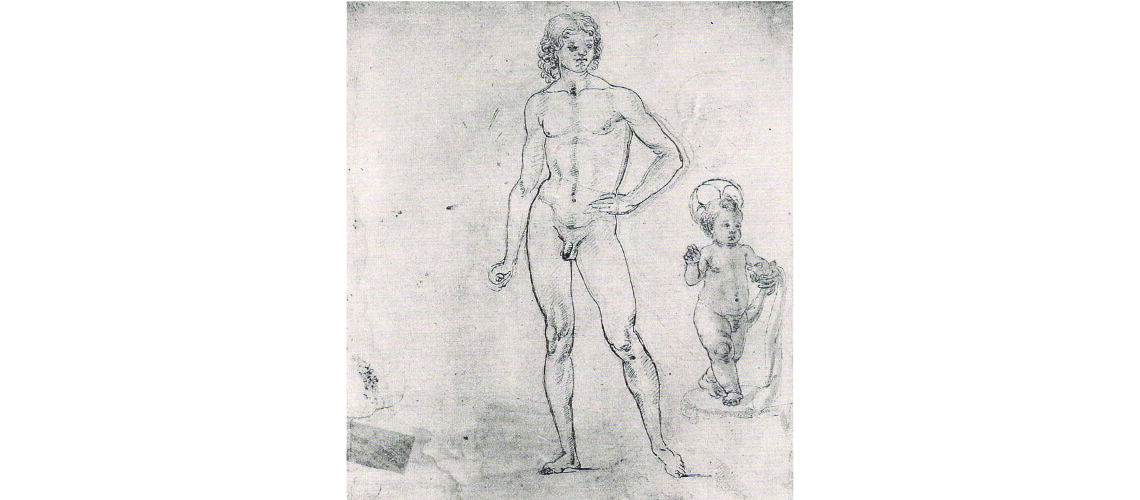

In the only drawing by Verrocchio’s workshop for the project, David is naked and there is no Goliath’s head.

Verrocchio, workshop, c. 1470, Louvre

E’ plausibile pensare che quando nel 10 maggio del 1476 la statua venne ceduta per 150 fiorini da Lorenzo e Giuliano dei Medici alla Signoria di Firenze, prezzo politico di grande favore (come ci dice il Gaye nel suo Carteggio inedito d’ artisti dei secoli XIV, XV, XVI) il Verrocchio abbia spostato la testa del David dal lato al centro delle gambe.

The conspiracy of the Picts

Piero dei Medici the Gouty on the death of his father Cosimo the Elder in 1464 took over the family business; it was then that his political enemies led by the Pitti family prepared a conspiracy to kill him in 1466, which Piero thwarted, capturing and exiling the organizers.

Very probably the figure of David by Verrocchio who kills the enemy by placing him in his own palace in via Larga where Donatello’s David was already on display in the courtyard was chosen as a symbol of Medici power.