Michelangelo and the David - Part I

The Masterpiece and its history

The History

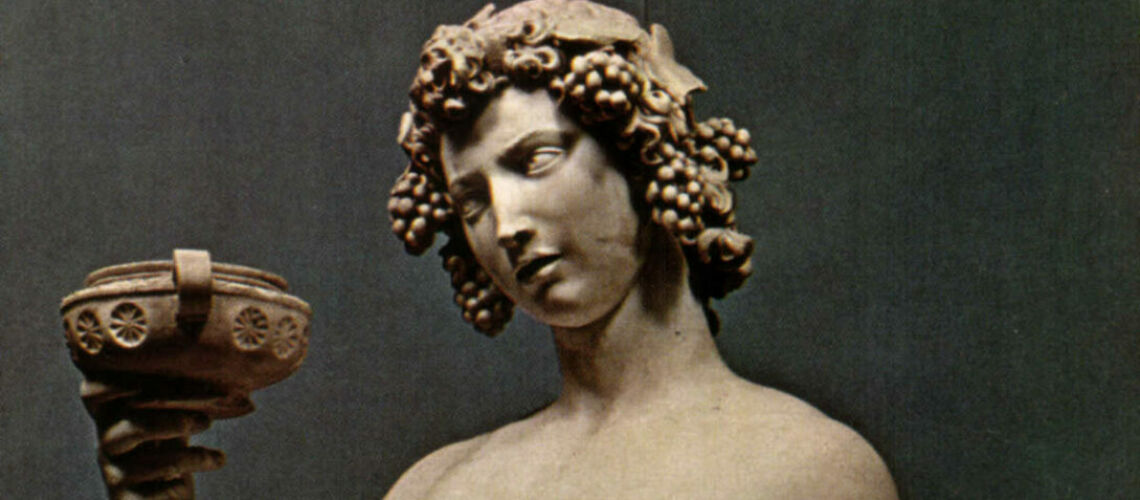

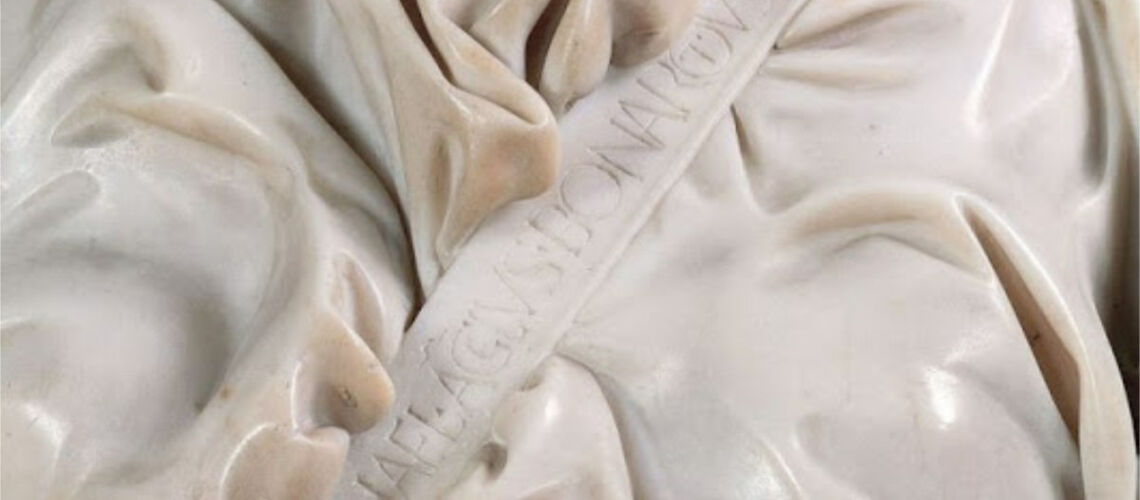

When Michelangelo signed the contract with the Opera del Duomo in Florence in August 1501 for the execution of the marble statue of a David, he was 26 years old, and had already executed a series of works, which later became “classics”; including in Rome, in the very last years of the 15th century, the Bacchus (now in the Bargello) and the Pietà in St. Peter’s in the Vatican, the only work he signed on the oblique waist on the chest of the Madonna “Michelangelus Bonarotus Florentinus Faciebat”.

Michelangelo’s Bacchus, Bargello National Museum, Florence

Pieta by Michelangelo, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican

Pieta by Michelangelo (detail), St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican

The contract for the David read …ad faciendum et perficiendum et perfece finendumquendam hominem, vocatur gigantem, abozatum, rachiorum novem ex marmore, existtentem in dicta opera, olim abozatum per magistrum Agostinum… de florentia et male abozatum…

That is, Michelangelo should have perfectly sculpted and completed a man defined as giant with a sketched marble existing in the Opera del Duomo, poorly sketched in the past by the Florentine master Agostino.

He began the work as required by a note in the contract:

Incepit dictus Michelangelus laborare et sculpire dicrum gigantem die 13 settembris 1501 ed die lunede mane, quamquam prius videlicet die 9 eiusden uno vel duobus ictibus scarpelli substulisset quoddam nisum quem habebat in pectore: seu dicta die incepit firmiter et fortier laborare, dicta die 13 et die lune summo mane…

That is, the aforementioned Michelangelo had begun to sculpt the said giant on the morning of September 13, 1501 although on the 9th he had removed a “knot” of marble from his chest with one or two strokes of the chisel: but he began to work on it steadily and more strongly on the said day Monday 13 in the morning.

With a few strokes of the chisel, Michelangelo had wanted to ascertain the quality and condition of the rough-hewn block of marble, which had remained outdoors for a long time having been entrusted to Agostino di Duccio years earlier, in 1463.

From a document of the Opera del Duomo dated 18 August 1464 (Poggi, Il Duomo di Firenze 1909)

it appears that it was the draft of a gigantic Prophet to be placed on one of the spurs of the Cathedral.

Agostino di Duccio left the sculpture sketchy, and therefore on 6 May 1476 the marble was given by the Opera del Duomo to Antonio Rossellino to be finished, but he too left it in a sketchy state.

Vasari, however, gives us other news:

“This was marble, nine arm lengths, in which by bad luck Simone da Fiesole had begun a giant, and the work was so badly tanned that it had pierced him between his legs and made everything badly managed and crippled; so that the workmen of Santa Maria del Fiore, who were working on this thing, without bothering to finish it, had abandoned it, and it had been like this for many years and was nevertheless about to wait.”

So Simone Ferrucci da Fiesole was the sculptor who left the badly rough-hewn block of marble

And it was not the Opera del Duomo that commissioned Michelangelo to sculpt and finish the block of marble, but it was Michelangelo himself who asked to be able to work it to try to get something out of it. He was thinking of the greatest sculpture performed in the Renaissance.

In any case, Michelangelo’s sculpture was constrained by the previous “sbozzo” and he was probably not yet sure how to reuse the block, what shape and movement it could give to his work. Which, moreover, had not yet been fully defined, in fact the contract mentions a hominem, vocatur gigantem, originally a Prophet to be placed outdoors on the spurs of the Cathedral.

The marble was in the courtyard of the Opera del Duomo, and there Michelangelo was to sculpt it. He had a turata built between walls and planks (Vasari, Vite) so that no one would see him at work, or see what and how he was creating.

It took Buonarroti three years and three months to complete the work. Probably, as he often did, he divided the time between the colossal giant and other sculptures that he had agreed to execute.

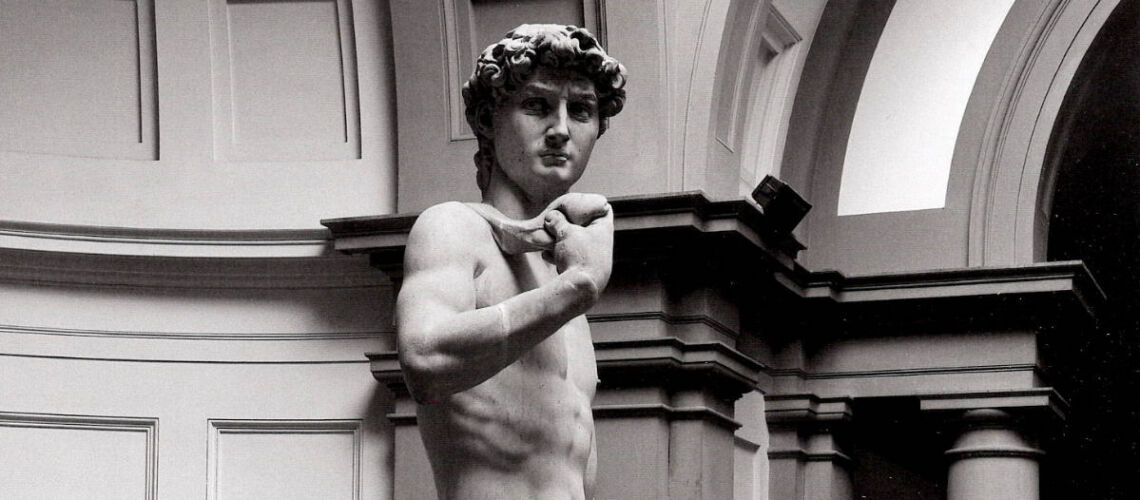

At the end of January 1504 the statue, the majestic David, was finished. Giorgio Vasari wrote that “he has taken the cry out of all the modern and ancient or Greek or Latin statues that they were… and certainly whoever sees this one should not bother to see other sculptures made in our times or in others by any creator.”

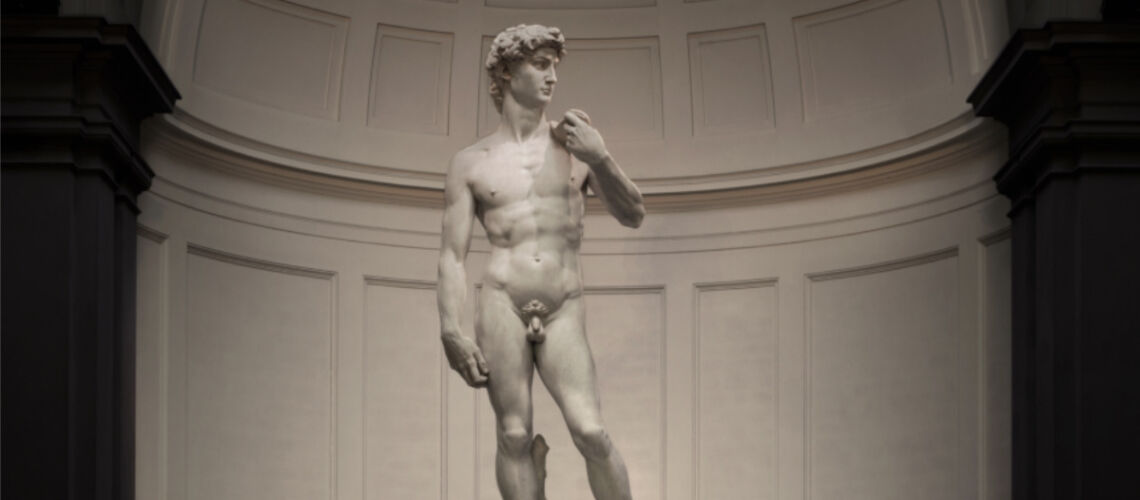

David by Michelangelo, Galleria dell’Accademia, Firenze

David by Michelangelo (detail), Galleria dell’Accademia, Firenze

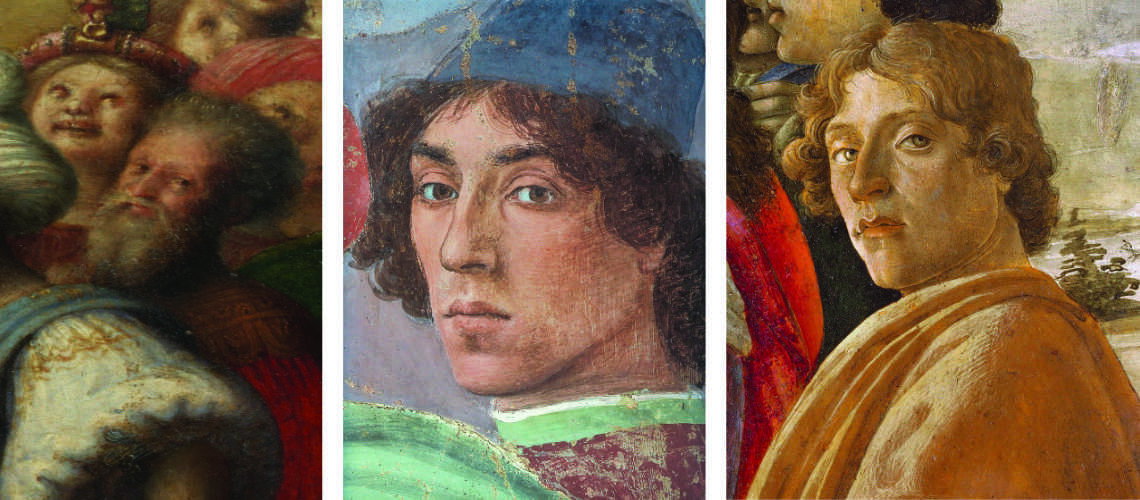

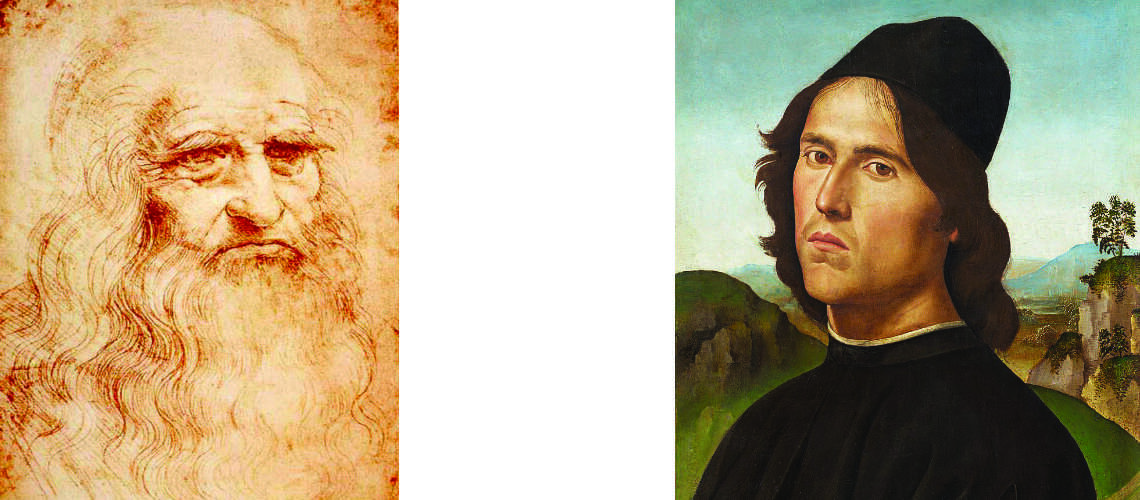

There was no more talk of hoisting it on a spur of the cathedral. However, it was necessary to decide where to place it. On 25 January 1504 a special commission was appointed, which was attended by the most famous and important artists of the city: Andrea della Robbia, Cosimo Rosselli, Francesco Granacci, Piero di Cosimo, Davide Ghirlandaio, Simione del Pollaiolo, Filippino Lippi, Sandro Botticelli, Antonio and Giuliano da Sangallo, Andrea Sansovino, Pietro Perugino, Lorenzo di Credi, Leonardo da Vinci.

|

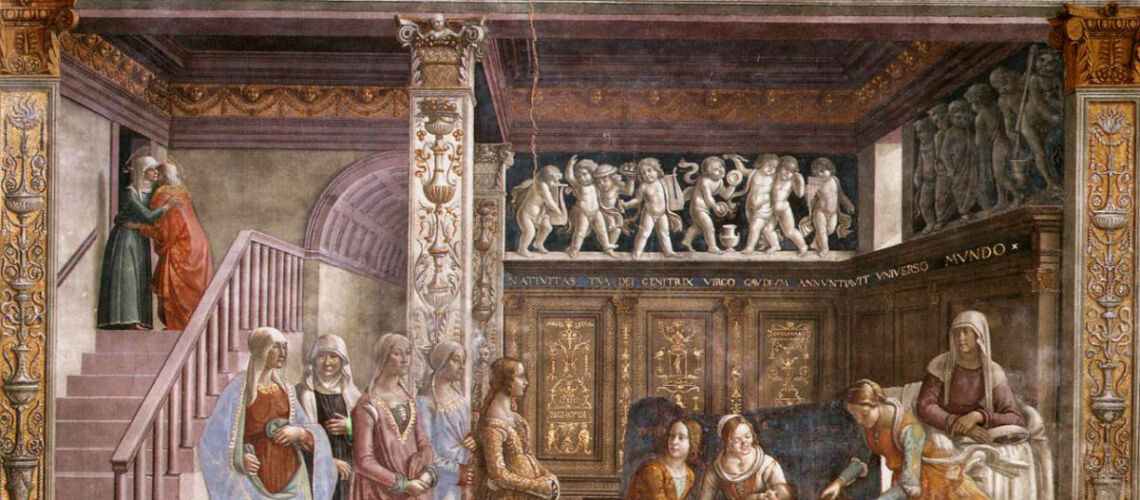

Andrea della Robbia, Andrea del Sarto, Devotion of the Florentines to the relics, 1510, detail, SS. Annunziata, Cloister of the Vows |

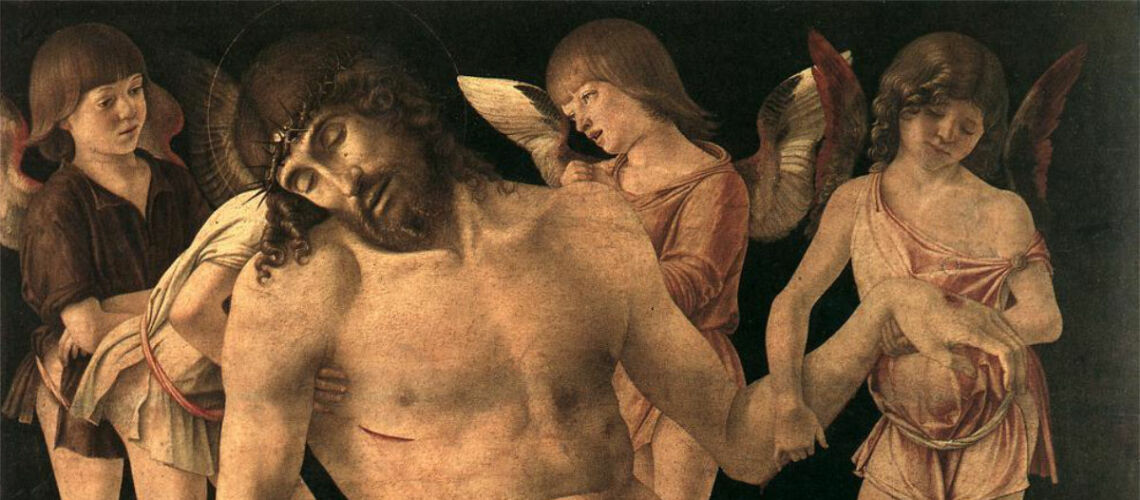

Cosimo Rosselli, Davide Ghirlandaio, 1490, Detroit Institute of Art |

|

Piero di Cosimo, self-portrait, 1515, Liberation of Andromeda, detail, Uffizi |

Filippino Lippi, Disputation of Simon Magus and Crucifixion of St. Peter, 1485, Brancacci Chapel |

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi, self-portrait, 1475, Uffizi |

|

Giuliano da Sangallo, Piero di Cosimo, 1505, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam |

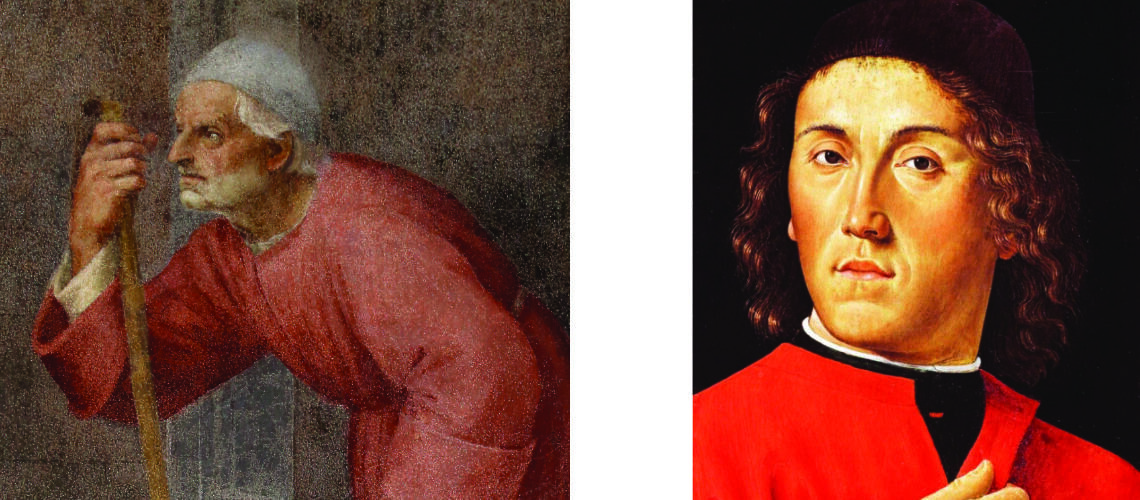

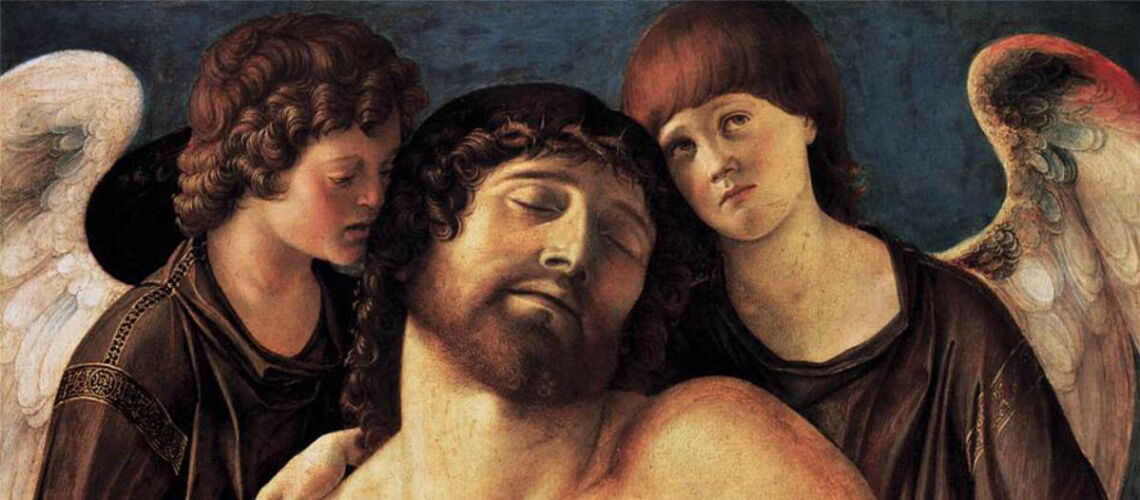

Pietro Perugino, Self-Portrait, 1500, Collegio del Cambio, Perugia |

|

Leonardo da Vinci, self-portrait |

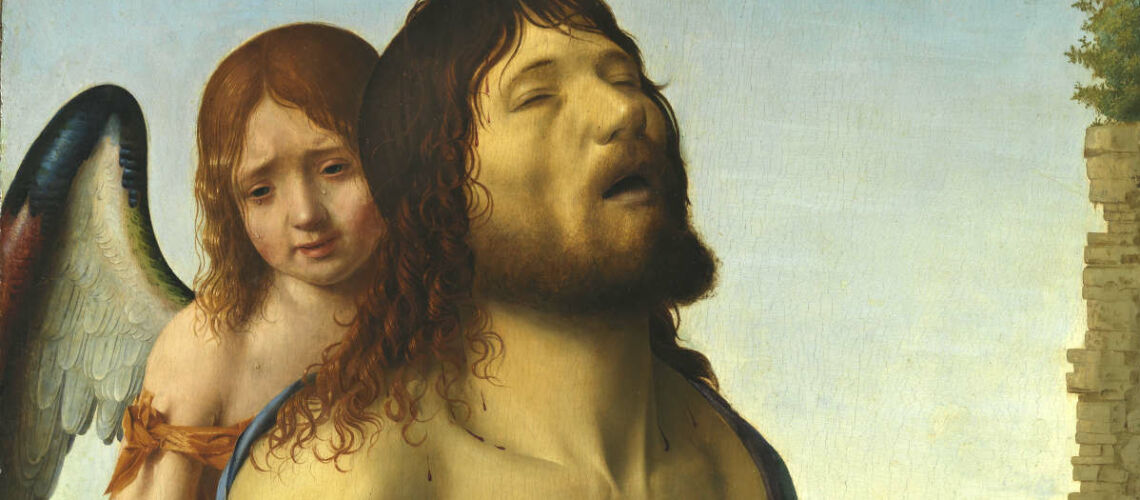

Lorenzo di Credi, Perugino, 1504, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

Leonardo da Vinci and Giuliano da Sangallo proposed placing the monument in Piazza Signoria under the Loggia dei Lanzi, in order to protect it from bad weather, leaning against the wall “with a black niche behind it like a cappelluzza”. In fact, they had noticed that there were “imperfections in the marble” which could have created problems with the duration and static nature of the outdoor sculpture.

The Herald of the Signoria of the Republic and Michelangelo instead proposed to place it either in the courtyard of the Palazzo della Signoria, or outside to the side of the Palazzo door, in any case outdoors.

Frictions arose so much that, Luca Landucci tells us in his Diary, it was necessary to mount guard at night at the David because it was stoned by those who did not agree on its positioning.

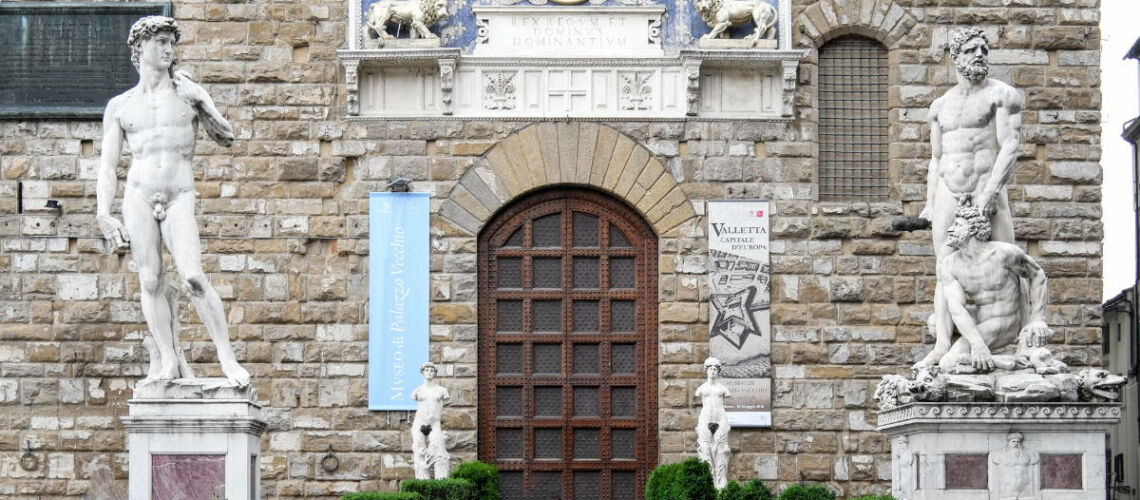

But only the rough draft wall of the Palace could be the background of the great marble, and it was decided to place it where it is still located in copy, but to do this they were forced on June 8, 1504 to move the bronze sculpture of Donatello, cast with lost wax method, Judith killing Holofernes, which was housed in the Loggia dei Lanzi, and on 11 June the red and white marble base was commissioned from Simone del Pollaiolo and Antonio da Sangallo.

Unfortunately, in 1842, in order to be able to move the David from the Arengario on the facade of Palazzo Vecchio, it was only possible to destroy the original base, on which the inscription EXEMPLUM SALUTIS PUBLICAE CIVES POSVERE was engraved, then reconstructing the base equal to the original.

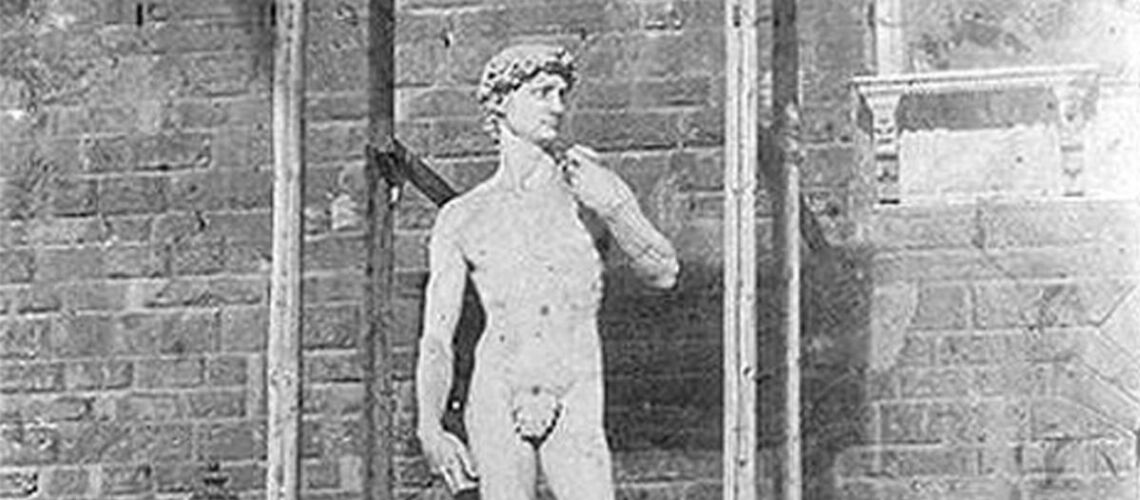

Provisional cover of David still on the base on 1504

David at the Academy on the redone base

Base of the replica of Piazza della Signoria

In July and August Michelangelo continued with the sculptural retouching of his masterpiece.

Vasari tells us the witty anecdote that took place in these two months:

“At this moment he was born when, seeing him on Pier Soderini, who pleased him very much, and while he was retouching him in certain places, he said to Michelagnolo that he thought that the nose of that figure was large. Michelagnolo realizing that the gonfalonieri was under the giant, and that his eyesight did not allow him to see the truth, to satisfy him, he climbed onto the bridge which was beside him behind him; and Michelagnolo quickly took a chisel in his left hand with a little marble dust that was on the planks of the bridge, and began to throw lightly with the chisels, he let the dust fall little by little, nor did he touch his nose which was. Then looking down at the gonfalonieri, whom he was watching, he said: Look at him now. I like it better (said the Gonfalonieri): you gave it life. Thus descended Michelagnolo, who laughed at himself, having pity on those who, for the sake of understanding each other, do not know what they are saying.”

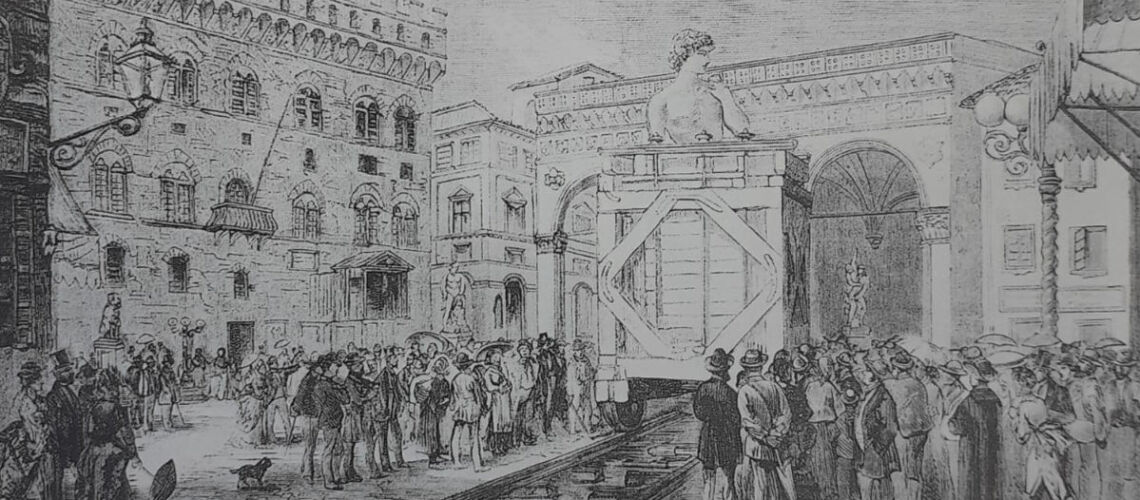

The transport of the giant from the Opera del Duomo to the facade of Palazzo Vecchio was another “feat” of no small importance, Vasari also summarizes this for us:

“…Because Giuliano da Sangallo and his brother made a very strong wooden castle, and they suspended that figure with the ropes from it, so that when it shook it would not break off, on the contrary it would always collapse; and with the beams on the flat ground with winches they pulled it, and put it to work. He made a noose to the rope, which held the figure suspended, very easily to slide, and tightened when the weight aggravated it: which is a beautiful and ingenious thing, which I have drawn by his hand in our book, which is admirable, sure, and strong to bind weights”

We had to wait until 8 September to have the David on its base permanently placed next to the door of the Palazzo Vecchio.

Palazzo Vecchio, detail of the door with the replica of David

In 1512, the base of the David was struck by lightning, but there was no obvious damage to the place. Instead, the statue suffered major damage on 26 April 1527 during the revolt for the expulsion of the Medici from Florence: republicans barricaded themselves in Palazzo Vecchio by throwing stones, furniture and tiles from the windows which, striking the left arm of the sculpture, broke it into three pieces and the sling splintered at shoulder height. Fortunately, Vasari and Francesco Salviati secretly collected all the pieces and went to hide them in Salviati’s house.

The restoration was carried out later, under the Duke of Florence Cosimo I dei Medici.

In 1813 the middle finger of the right hand was damaged and was rebuilt in 1843 by Aristodemo Costoli who, in an attempt to clean the hand of concretions both mechanically with steel brushes and chemically with hydrochloric acid, damaged the surface. The damage was already done, but to try to protect it from the rain, the statue was temporarily covered.

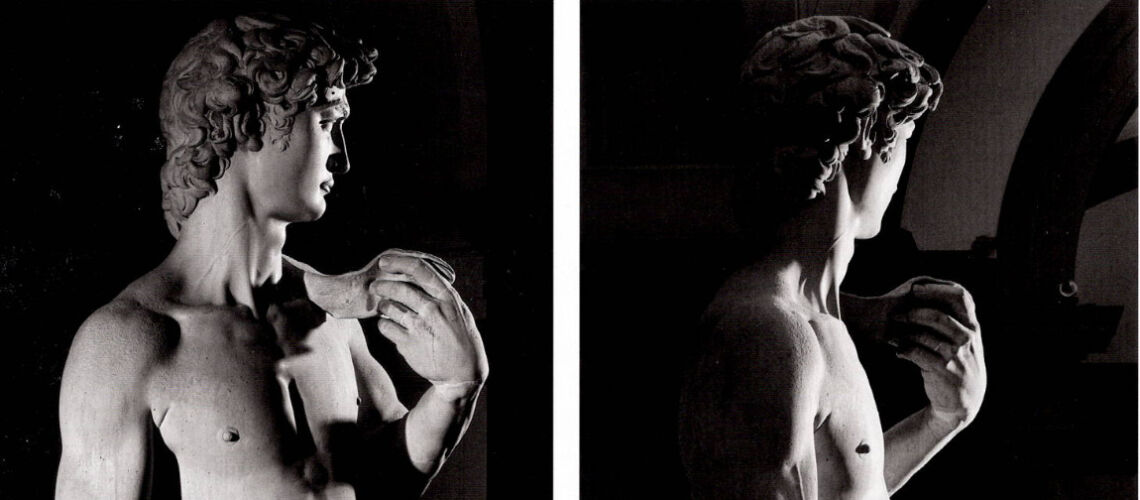

David by Michelangelo, Galleria dell’Accademia, Firenze

David by Michelangelo (detail), Galleria dell’Accademia, Firenze

The last damage was inflicted in 1991 on the left foot by a self-styled protester: a hammer blow chipped the first three toes, then restored with the recovered fragments.

The exposure of the David to the elements for about three centuries had caused its surface to float, especially where the rain was pouring (shoulders and upper part of the hair) and opened a series of small holes in the marble, the so-called “taroli”; so it was decided to protect the work by bringing it inside the Academy gallery.

For this purpose, the architect Emilio de Fabris built a new grandstand illuminated by a skylight,

David by Michelangelo (detail), Galleria dell’Accademia, Firenze

and in August 1873 the David was transported to the Accademia Gallery on a special carriage on which it was harnessed, a carriage that was made to slide on wooden rails.

It took five days to transport the nearly seven-ton statue; the torrid climate in fact allowed to work only in the coolest hours from four to eleven in the morning.

David by Michelangelo (detail), Galleria dell’Accademia, Firenze

Model of the chariot for transporting the David to the Galleria dell’Accademia, Casa Buonarroti

Model of the chariot for transporting the David to the Accademia Gallery, Alinari photo

Model of the chariot for transporting the David to the Accademia Gallery, New Universal Illustration, year II no. January 6-18, 1874, p. 48