Michelangelo and the David - Part II

The Masterpiece and its history

The History

Michelangelo had a splendid life but also a very difficult one, which he often complained about: discouragement due to body fatigue, lack of friends of any kind, political and religious crises, extreme avarice towards himself and his others (but not with family members he felt guilty towards) so much so that he fled Florence while he was directing the fortification works for the nearby siege of the city, for fear of seeing his own money taken to support the expenses of the war, from the passion senile for the young and beautiful Tomaso Cavalieri, to the spiritual love for Vittoria Colonna.

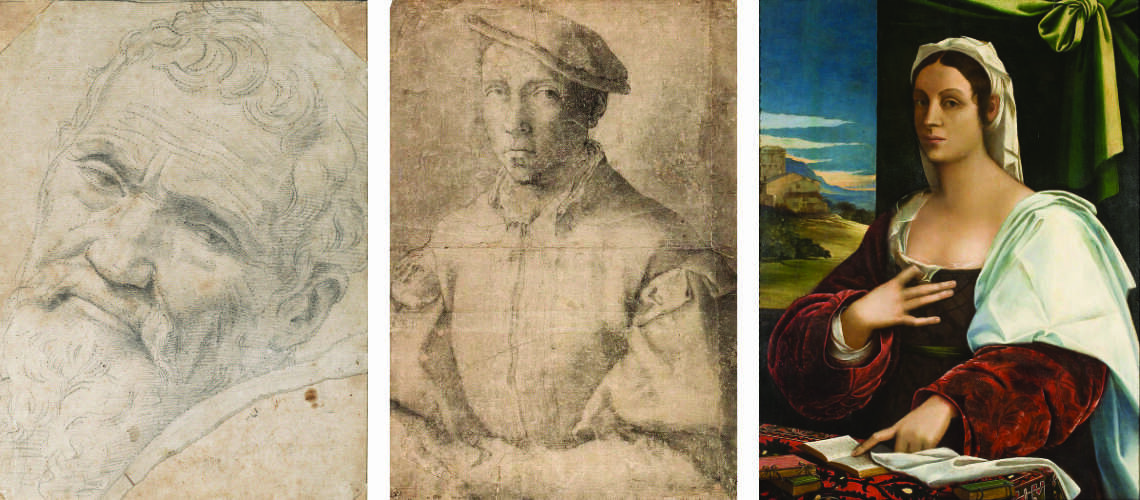

| Michelangelo, portrait, Daniele da Volterra | Tommaso dei Cavalieri, Michelangelo, Musée Bonnat, Bayonne | Vittoria Colonna, Sebastiano del Piombo, National Museum of art of Catalonia, Barcelona |

At the same time his art was immediately admired and venerated by his contemporaries, it fascinated the great personalities he commissioned, historians, his disciples and contemporary and subsequent artists. His life was written by the biographers Giovio, Vasari, Condivi while he was still alive. He was admired by Cellini, Tintoretto, Buontalenti, Greco.

| Giorgio Vasari, Self portrait | Paolo Giovio, Cristofano dell’Altissimo, Uffizi |

His sculptural style is the watershed between the Renaissance, of which it is the ripe fruit, and the beginning of Mannerism. In the unscrupulous use of the “unfinished” Michelangelo brings an impressive modernity to sculpture for the first time, both unresearched as in the works he actually could not or did not want to finish, and where he used it in the works in which unfinished areas deliberately appear alongside finished and polished areas.

Many hypotheses have been made to explain the meaning of this way of sculpting, and still the critics do not agree. The fact remains that it creates deep sensations and emotions in the viewer.

| Michelangelo, Tondo Taddei, Royal Academy, London | Michelangelo, Pietà Bandini, 1550, detail, Opera del Duomo of Florence |

Il David

When Michelangelo dictated his autobiography to Condivi, he wanted to highlight that he always did everything alone without help, even the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, and even alone he declares that he never used the normal methods that sculptors have always used: he left almost no preparatory drawings for his sculptures, having burned them all before he died, he never made clay models, even if there is a life-size clay and wax model of his at the Academy of Design Arts.

Clay model of river divinity, Michelangelo, 1524, Academy of Design Arts

For the David the situation in which Michelangelo found himself was different, the block of marble had already been roughed out even if badly. Michelangelo had to think the shape of his David forced from the existing blank. However, he was able to perform perhaps his greatest masterpiece even with these difficulties.

David is the young biblical hero who, challenging the giant warrior Goliath to a duel, kills him with a stone thrown with a slingshot and then takes him off with his sword, making the Israeli army led by King Saul win against the Philistines.

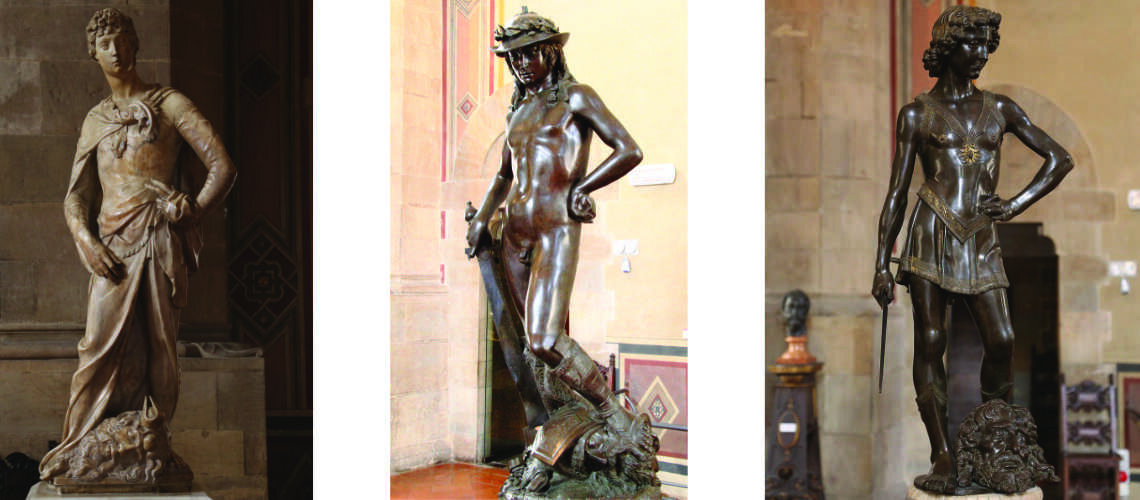

Michelangelo sculpts him with the stone still to be thrown, Goliath is still alive; in the two Davids by Donatello, the one in marble and the one in bronze, Goliath was killed and his head was cut off, the sword also appears in the bronze, as well as in that of Verrocchio.

| Donatello, David, 1408, Bargello Museum | Donatello, David, 1440, Bargello Museum | Verrocchio, David, 1469, Bargello Museum |

The Florentine Republic was led albeit indirectly by the Medici family, who always found it prudent to highlight and insist on freedom from tyranny.

Already in 1416 the Signoria of Florence had purchased the marble David that Donatello had sculpted in 1408 placing it in the Sala dell’ Orologio of Palazzo Vecchio, a symbol of freedom against any dictator. At his feet he had carved the inscription Pro patria fortiter dimicantibus etiam adversus terribilissimos hostes Dii prestant auxilium, i.e. The gods give support to those who fight vigorously for their country even against the most formidable enemies.

Cosimo the Elder also wanted the statue of a bronze David for his courtyard of Palazzo Medici in via Larga to underline how the Medici too were advocates of freedom against tyranny, and asked Donatello for it who sculpted a more pagan and naked David which we know to have been in 1469 in his Palace. However, when the Medici were expelled from the city in 1495, the people who raided the Palazzo transported the statue to Palazzo Vecchio as a symbol of the freedom of the Republic.

Cosimo the Elder, Pontormo, 1520, Uffizi

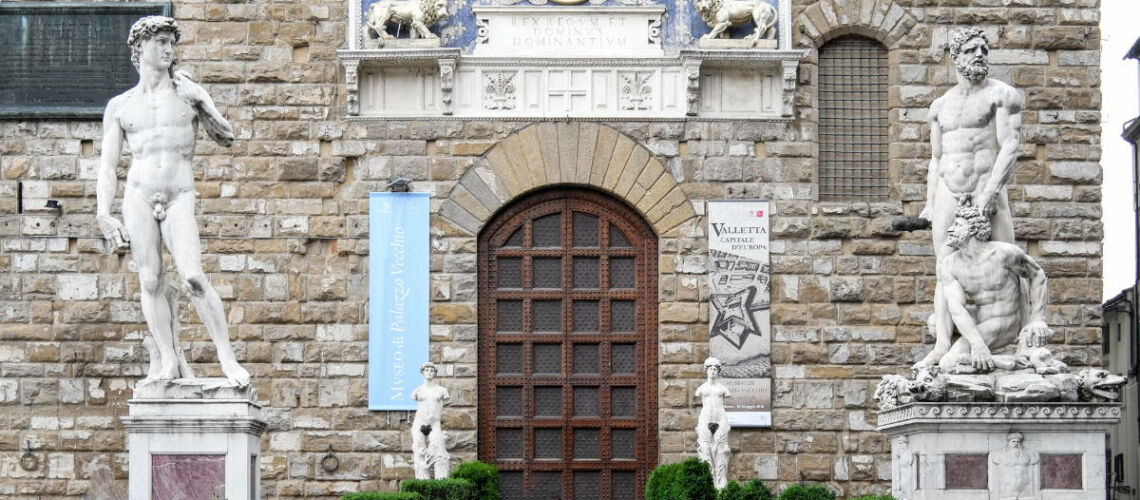

The message of Michelangelo’s David was the same: God would protect the city of Florence and its Republican government based in Palazzo Vecchio from any enemy of freedom.

Michelangelo’s David is a completely naked young man, and it is the first time since Rome that a large statue has been executed completely naked.

The pose of resting the weight on one of the two legs, which leaves the other free as in the classical heroes at rest, which happens to the various Davids, derives from classical art and also reappears from the little Hercules symbolizing the Force, present in the pulpit of the Baptistery of Pisa, sculpted by Nicola Pisano.

Nicola Pisano, Hercules, Pulpit of the Baptistery, 1260, Pisa

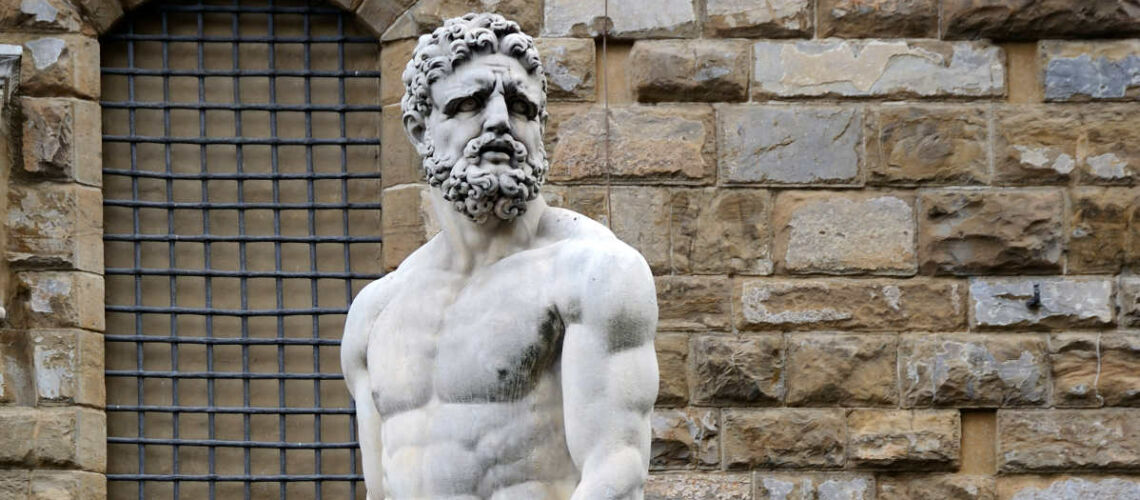

When in 1537 Cosimo I dei Medici becomes Duke of the Republic of Florence, he chooses to change the symbol, no longer the republican David, but Hercules against whose strength it is useless to fight.

He has the statue of Hercules who conquers Cacus sculpted and, while leaving Michelangelo’s David in its place, he places it on the other side of the Porta del Palazzo Vecchio, the meaning of which is clear: God is no longer with the Republic, now he is Hercules , symbol of Cosimo, and of the new branch of the Medici, which commands.

Hercules and Cacus, Baccio Bandinelli, 1534, Piazza della Signoria

Ercole e Caco, Baccio Bandinelli, 1534, Piazza della Signoria