THE BYZANTINE BRONZE DOOR OF SAN PAOLO FUORI LE MURA IN ROME

This door is part of the group of bronze doors made in Constantinople and sent to Italy, recognizable by the particular style of the damascening designs on the panels, of Byzantine type but slightly Westernized.

Just a few years after 1054, the year of the schism between the Eastern and Western churches, in 1070 the door for the Church of Saint Paul Outside the Walls was cast in Constantinople and immediately shipped to Rome.

It was donated by Pantaleone of Amalfi, “Consul Malfigenus,” as the dedicatory inscription on the door read. Pantaleone, a very wealthy merchant from the flourishing colony of Amalfi in Constantinople,

donated it to the Basilica of Saint Paul in Rome, just as he had donated it to the church of Amalfi, the Basilica of Montecassino, and the sanctuary of Monte Sant’Angelo.

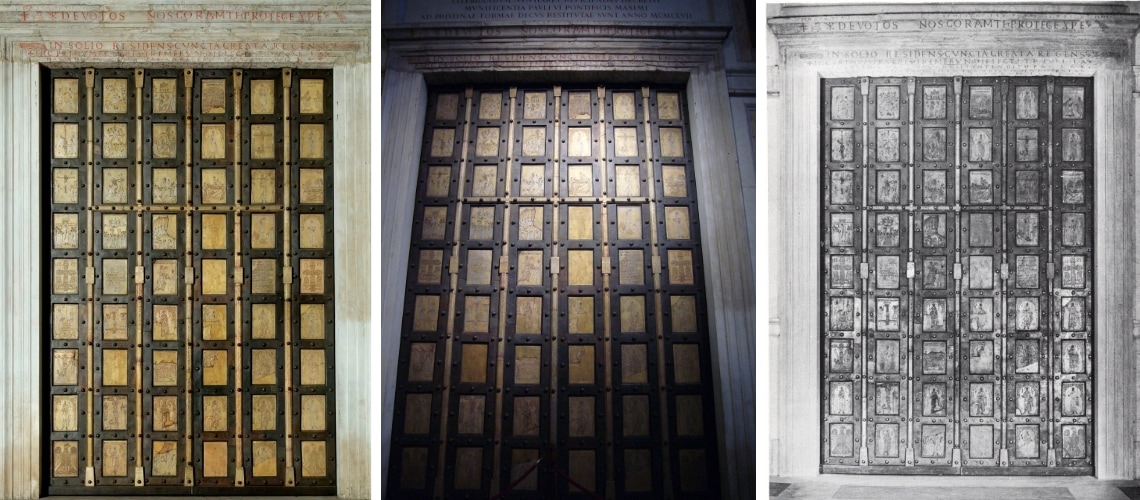

The door we see, although original, is the result of the 1966 restoration, and highlights how in Byzantine bronze doors everything revolved around the design of the intaglios and not the volume of the sculptural parts. No three-dimensional sculpture was required, because the doors had to be

large panels of shiny golden yellow metal “painted” with intaglios, and never patinated; in fact, they were periodically washed to maintain their brilliance (Photos 1, 2, 3).

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

Evidently the schism of 1054 had not interrupted artistic and commercial exchanges between East and West, and had not affected the Roman taste for Byzantine objects; so much so that Hildebrand, the influential figure in the papal circle, requested from Pantaleone Amalfitano, consul in Constantinople, the door in clear Byzantine style.

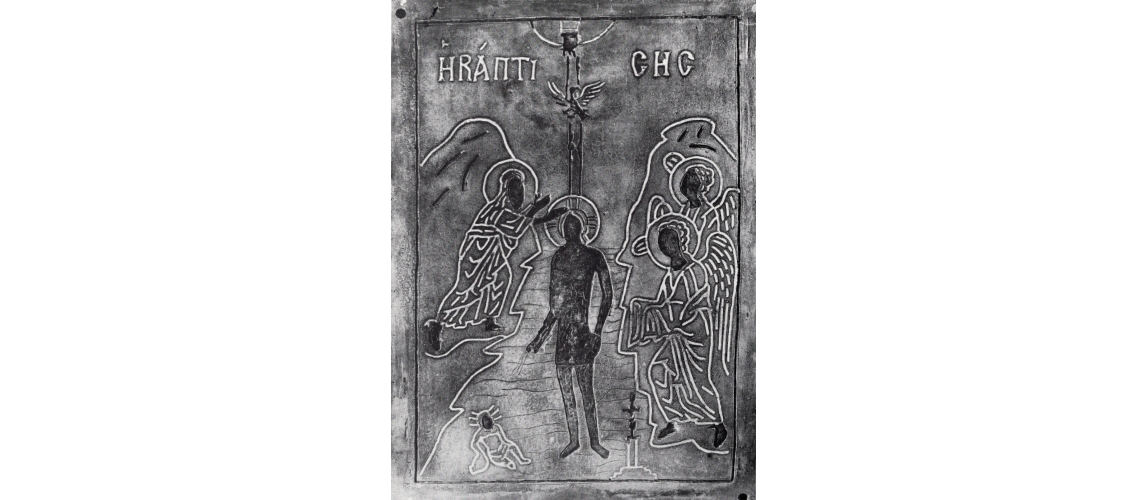

The door (5 meters high and 3.42 meters wide) was composed, like other Byzantine doors, of 54 individual and separate inlaid brass panels, about half a centimeter thick (Photo 4); the panels were fixed to the large wooden door with brass frames nailed to the wood. It was therefore a cladding of metal panels and frames on the wood (Photos 5, 6). These panels were cast using the “stirrup” technique, which is more suitable (and easier and quicker) for obtaining thin, flat sheets than lost-wax casting.

4

| 5 | 6 |

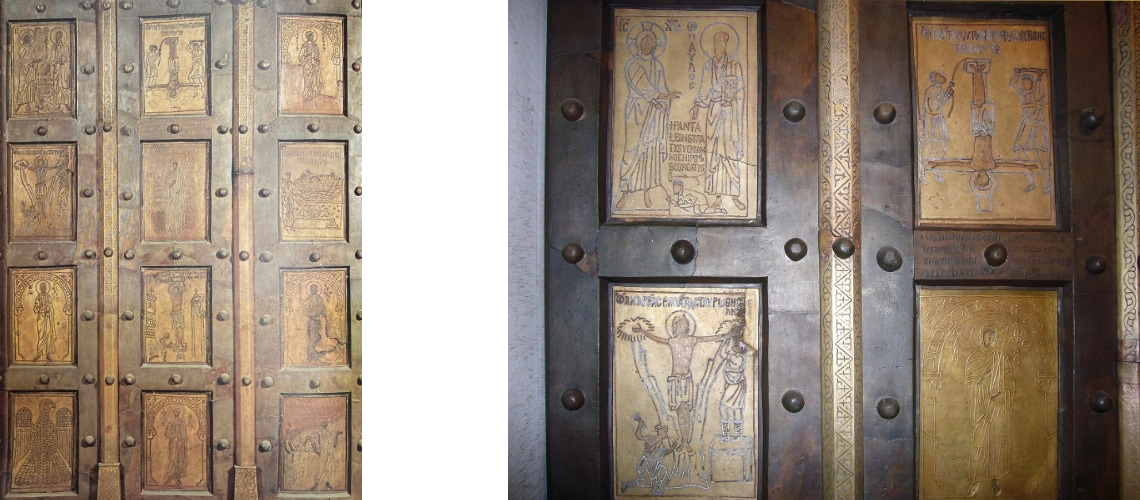

Nel luglio del 1823 la basilica di San Paolo subì un rovinoso incendio che distrusse gran parte dell’ edificio; della porta bronzea furono recuperati quanti più frammenti possibile e conservati in un locale attiguo alla sacrestia. Parte dei pannelli persero l’ argento inserito in origine nei solchi dell’ageminatura (Foto 7, 8, 9, 10).

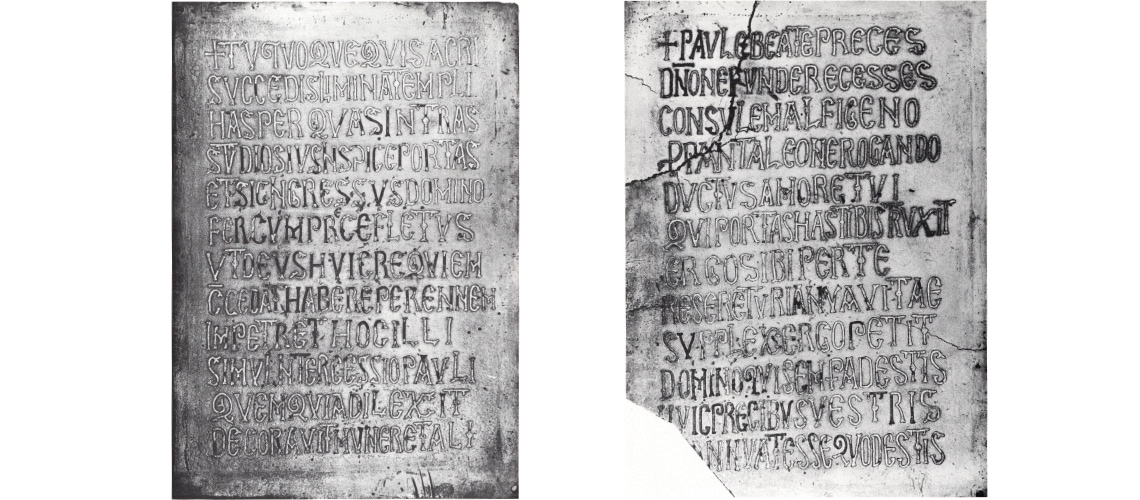

| 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 |

La porta presentava due iscrizioni: una bilingue in greco e in siriaco sulla cornice sotto la Crocifissione di San Pietro e ricordava il fonditore Staurakios (“fu fatta per mano mia, di Staurakios il fonditore. Voi che leggete pregate anche per me”) ed è andata perduta nell’ incendio della Basilica (ma ne esiste una copia fedele nel corpus ottocentesco dei disegni di Seroux d’ Agincourt);

la seconda è comparsa nel restauro del 1966 e ricorda l’artista Theodoros (“O santi Pietro e Paolo, soccorrete il vostro servo Theodoros che ha disegnato queste porte”)

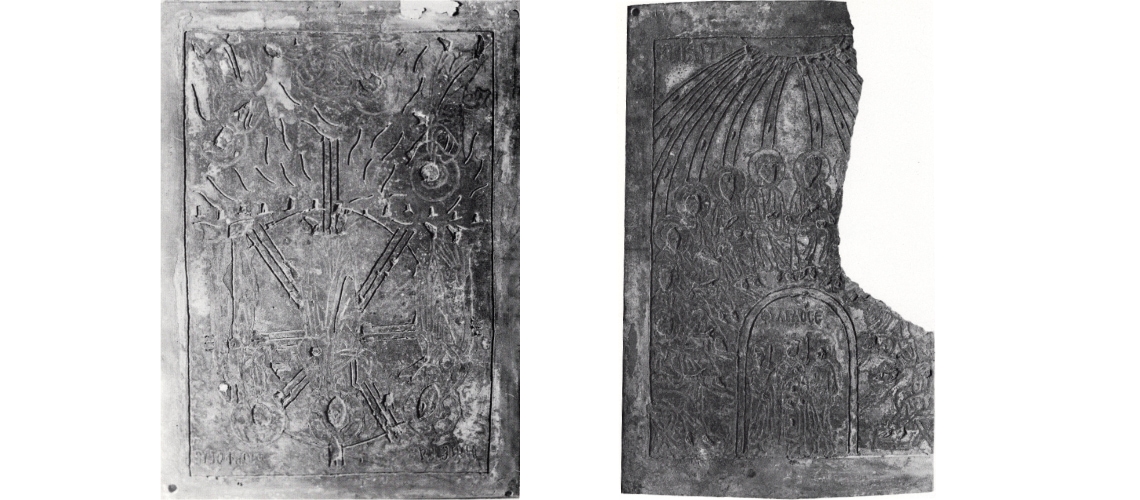

Un’ antica terza iscrizione ci viene dalla “Historia delle Stationi di Roma” del 1588 di Pompeo Ugonio (Foto 11), che aveva visto scritto sulla porta stessa:

“Anno 1070. Ab incarnatione Domini, temporibus / Domini Alexandri sanctissimi Papae Quarti, et / Domini Ildebrandi venerabilis Monachi et / Archidiaconi, constructae sunt portae istae / in Regia Urbe Costantinopoli adiu / vante Domino Pantaleone Con / sule, qui illa fieri iussit.” che confermava la costruzione della porta in Costantinopoli nel 1070, ma anche questa iscrizione è andata persa nell’ incendio del 1823.

11