Michelangelo in Florence, the Slaves

In November 1518 Michelangelo, in Florence for the façade of the Basilica of San Lorenzo, purchased a piece of land in via Mozza (today the last part of the current via S. Zanobi which opens onto via delle Ruote) and in 1519 there he had his sculpture studio built of around 200 m2, with a small garden at the back.

Before moving permanently to Rome in 1534, he had worked on the Medici Tombs for the New Sacristy of the church of S. Lorenzo.

Michelangelo, wooden model for the façade of San Lorenzo, 1518, Casa Buonarroti

On 9 April 1519, a block of marble that he had purchased in Carrara, in the Fantiscritti quarry, was brought to him in a cart pulled by 5 oxen, and subsequently many others for the New Sacristy and for the enormous project of the Tomb for Pope Julius II.

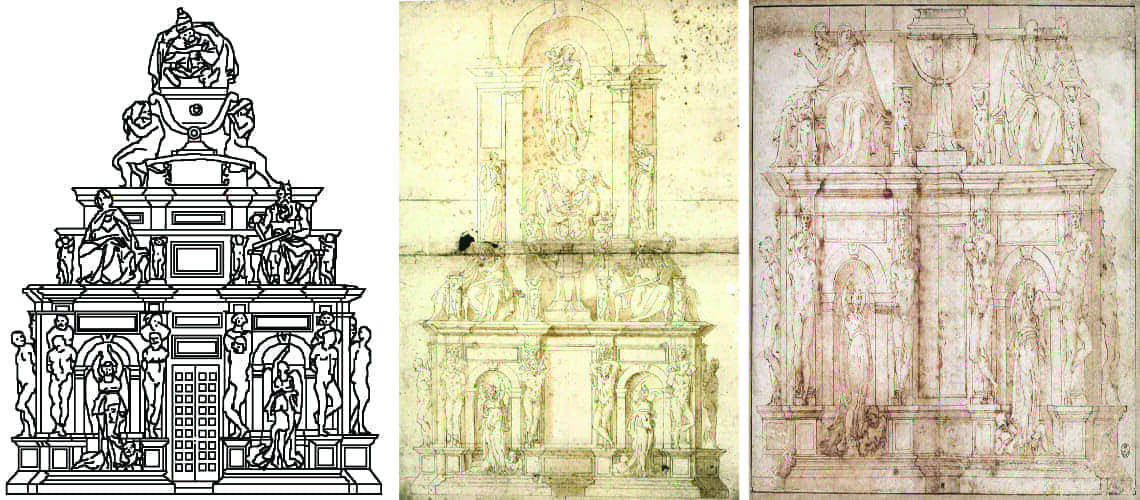

| Diagram of the first project of the tomb of Julius II. Slaves were provided at the base | Giacomo Rocchetti, drawing of the tomb of Julius II foreseen in the second contract. from 1513, Slaves are still present, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin | Michelangelo, lower part of the drawing of the tomb of Julius II foreseen in the second contract of 1513, the Slaves are still present, Uffizi |

In 1534 he moved permanently to Rome, leaving wax and clay models, marbles and sculptures in his studio in Florence, which were stolen during the siege of Florence in 1529. Some were later recovered or remained, in particular the four Prisoners (or Slaves) unfinished, also designed for the tomb of Julius II.

In fact, in the first pharaonic project, this should have had 16 to 20 prisons one and a half times larger than life at the bottom, which emerged from and emerged from the block of marble. As we know, the first project did not come to fruition because in 1513 the tomb was redesigned in smaller forms where the Prisoners should have become 12. In 1516 a third project made the tomb even smaller and the Prisoners should have become 8. In the following 2 other projects increasingly reduced in 1526 and 1532 they would become 4. In the definitive project of 1542 (the sixth) the Prisons were no longer included.

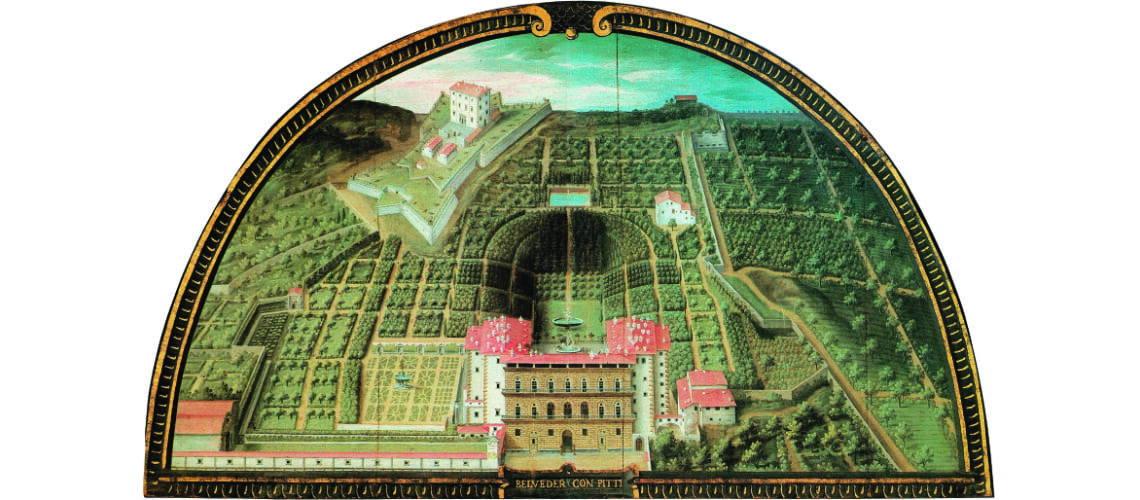

In 1550 Eleonora of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I, purchased the Pitti Palace to move her family and the entire court there, including the land on the rear façade of the Palace, which she had transformed into the splendid Boboli Gardens.

Giusto Utens, Lunette with Pitti Palace and Boboli Gardens, 1599, Villa La Petraia

The four Florentine Prisons included in the project for the tomb of Julius II and then no longer needed remained in the studio in via Mozza and were donated in 1564 by Leonardo Buonarroti, Michelangelo’s nephew, to Grand Duke Cosimo I.

Duke Francesco I, son of Cosimo and his successor, had Buontalenti build an artificial cave with several rooms covered with fake rocks between 1583 and 1593 (Vasari designed the entrance), in which he had the 4 Prisoners set as if they were struggling to be born and out of the rocks. And they remained there until the early 1900s when they were taken to the Accademia Gallery.

They were subsequently reinserted into the original positions of the plaster replicas.

Boboli Gardens, Vasari’s entrance to Buontalenti’s cave

The anatomical study of the Bearded Slave is surprising: the muscular torso in torsion, the right arm raised in the exceptional pose of holding himself and clutching his bent head. Despite being the most finished of the four, the powerful spread legs held by a band, still united to the rock that generates them as well as the still unformed left hand, give an exceptional sense of awakening, of powerful strength, of a Pagan divinity in the process of appear in the Olympus of the gods, characteristics made vibrant also by the surfaces that show the marks of the chisels with which Michelangelo was giving birth to them.

Michelangelo, Barbuto Slave, Accademia Gallery

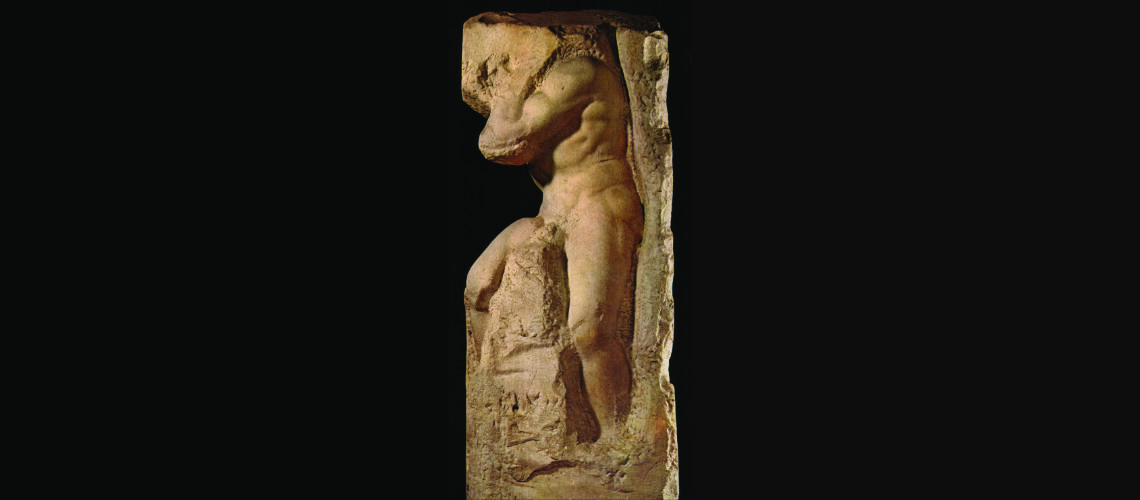

The Slave Atlas, unfinished, seems to have his head inside the block of marble which holds with effort both his legs spread apart and bent and his left arm whose muscles are in tension. The figure tries to free itself from the stone from which it was born and it is the unfinished state that amplifies and highlights the energy that the Slave is about to unleash.

Michelangelo, “Atlas” Slave, Accademia Gallery

The Awakening Slave: a powerful male figure turns in the marble that still grips him. His face is rough-hewn. The right leg and the left arm, although still hinted at, unlike the torso which is finished, form an “S” curve which amplifies the sensation of awakening not yet free from the rock in which it is stuck. Also in this Slave, as in the other three, the limbs and anatomies are massive and powerful.

Michelangelo, Awakening Slave, Accademia Gallery

The Young Slave is little more than rough-hewn, the only part to which Michelangelo gave a first smoothing is the knee: the part of the body that protrudes and which first emerged from the marble. The giant seems to wake up as he emerges from the rock that wants to give birth to him. Even the pose of the bent arm covering part of the face and the outstretched knee speak of a birth. And in fact he is the youngest of the four. The only muscular masses are those of the torso, barely mentioned, but even so they speak of divinities of great strength and power, power that the slave takes from the earth and the rock from which he is detaching himself.

Michelangelo, Young Slave, Accademia Gallery

| Michelangelo, Young Slave, cast in posthumous statuary bronze from a mould made on the original byFonderia Artistica Ferdinando Marinelli of Florence | — — — | Michelangelo, Barbuto Slave, Posthumous statuary bronze casting from a mould made on the original by Fonderia Artistica Ferdinando Marinelli of Florence |