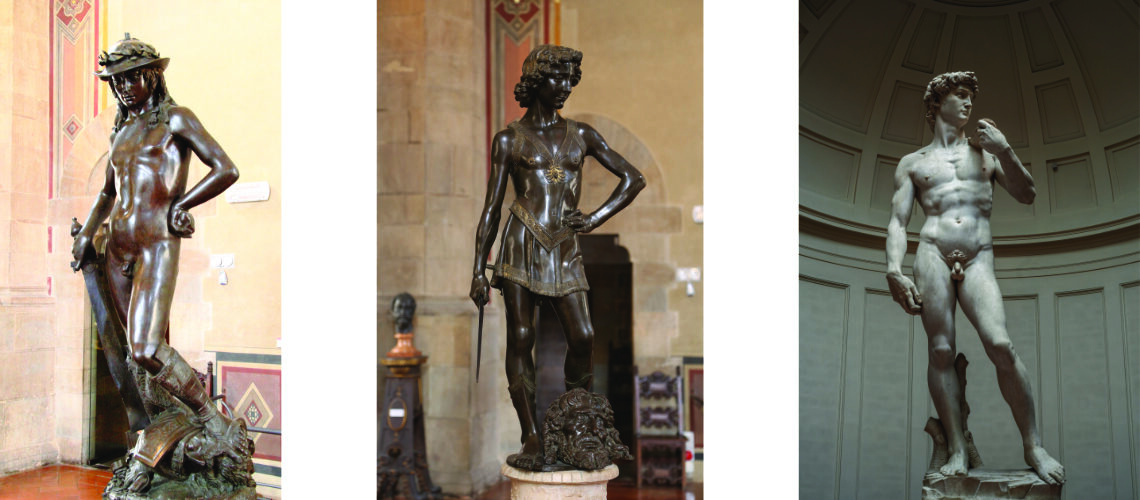

Michelangelo, the Bacchus

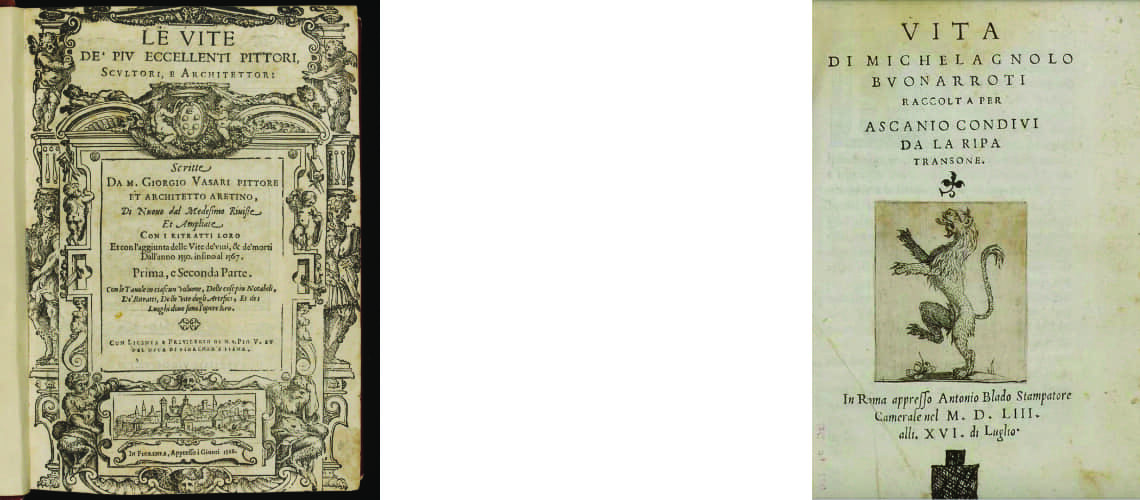

Vasari in the Lives, referring to Michelangelo, writes of:

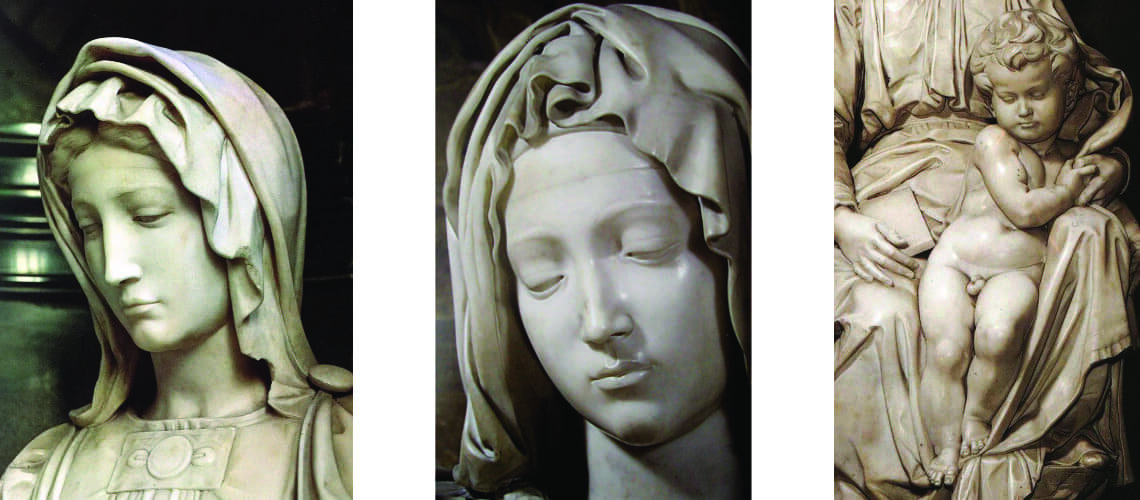

…un Dio d’amore, d’età di sei anni in sette, à iacere in guisa d’huom che dorma…

[…a God of love, aged from six years to seven, lying in the guise of a sleeping man…]

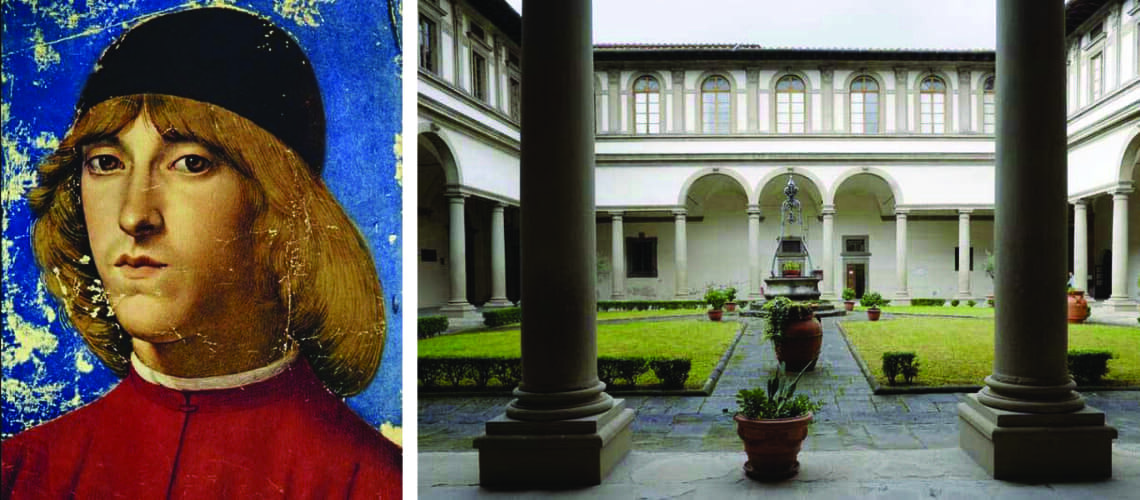

alluding to the marble statuette that Michelangelo had sculpted in 1496 upon his return to Florence, when he was once again hosted by Lorenzo dei Medici the Popolano, cousin of Lorenzo the Magnificent.

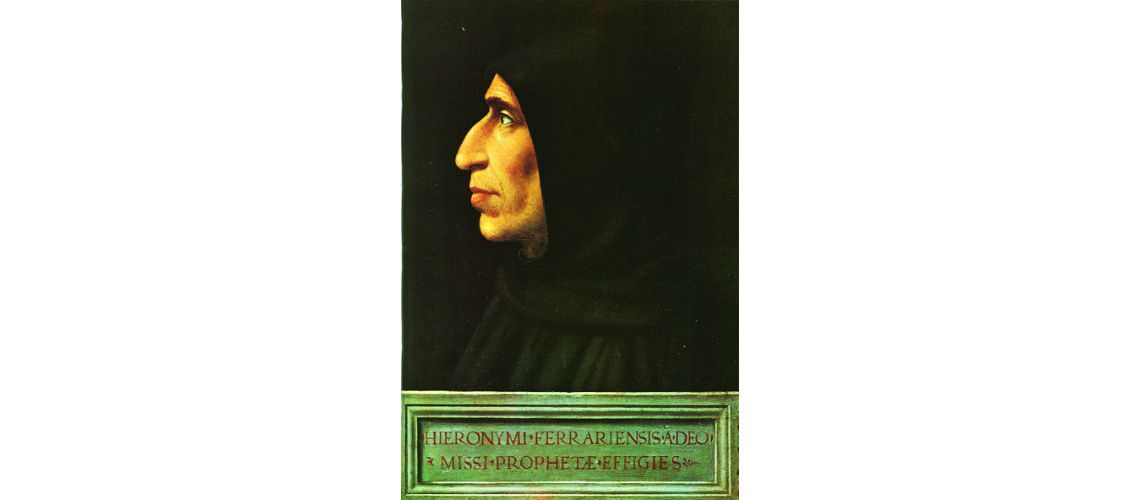

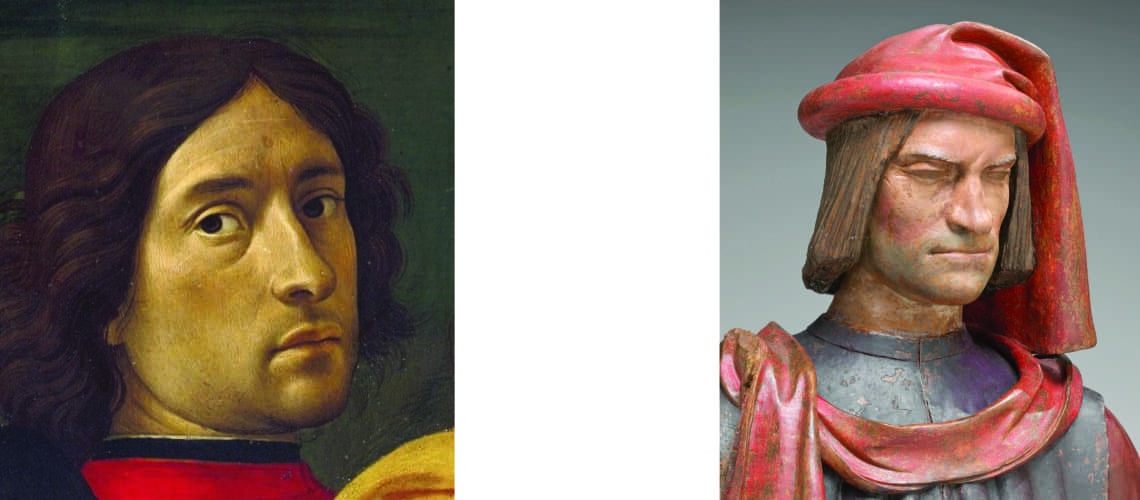

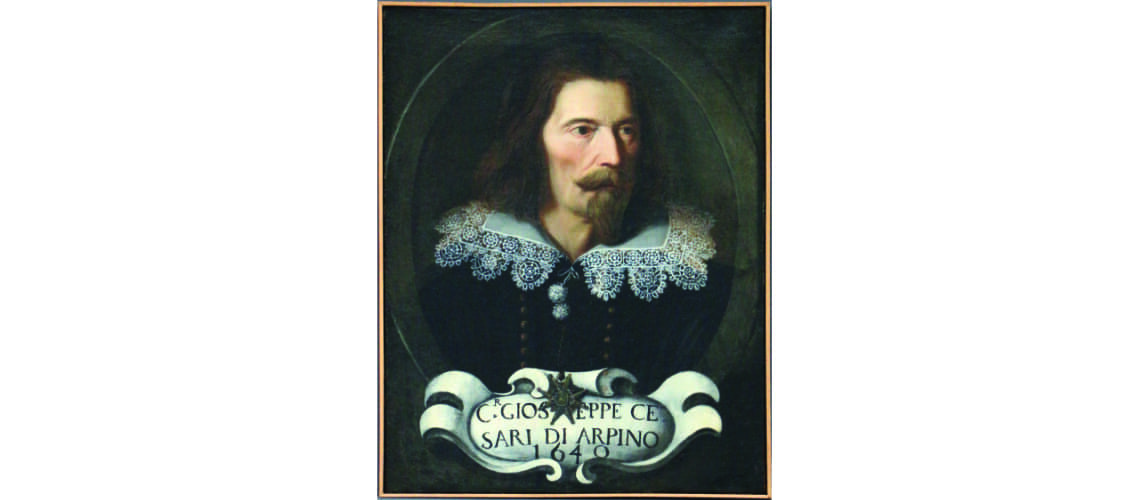

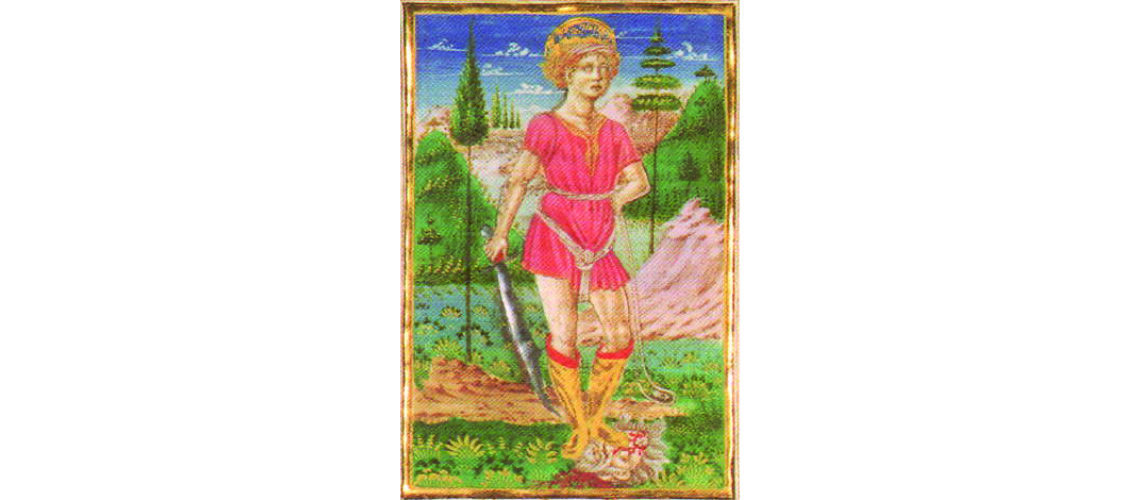

Lorenzo dei Medici “il Popolano”, Botticelli, 1479, Palazzo Pitti.

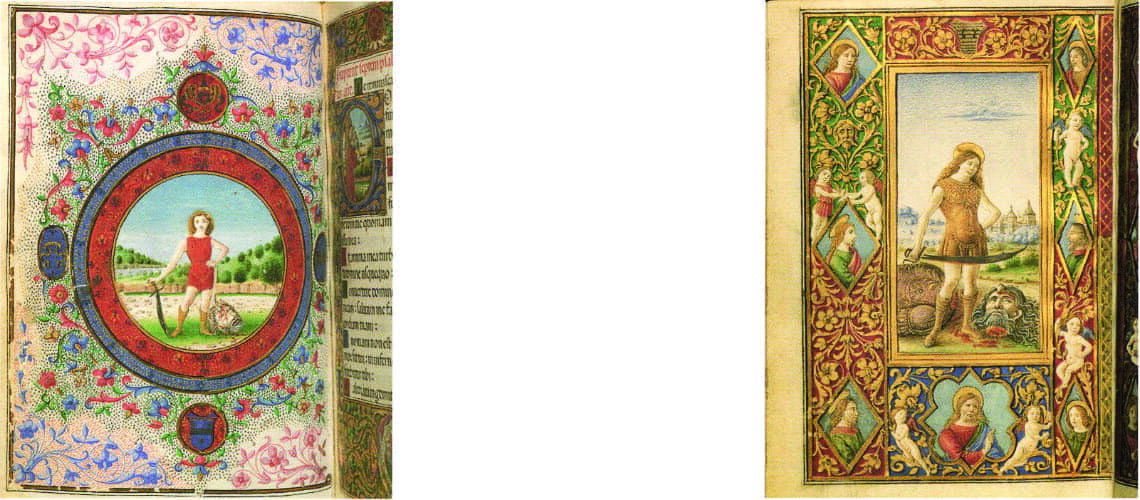

We also know about it thanks to a letter from Antonio Maria Pico della Mirandola dated 1496 to Isabella d’Este, where he writes:

… Un Cupido che giace e dorme posato su una mano: è integro ed è lungo circa 4 spanne, ed è bellissimo; c’è chi lo ritiene antico e chi moderno; comunque sia, è ritenuto ed è perfettissimo.

[… A Cupid lying and sleeping resting on one hand: it is intact and is about 4 spans long, and it is beautiful; there are those who consider it ancient and those who consider it modern; in any case, it is considered and is very perfect.]

The statue was “four spans” long, i.e. about 80 cm, but has been lost, and the proposed identification with the Sleeping Cupid preserved in the Museum of Palazzo San Sebastiano in Mantua is much discussed and unlikely.

Sleeping Cupid, Palazzo San Sebastiano City Museum

It was commissioned by the Medici. It was 1496, the year in which Savonarola and his followers censored every work of art considered licentious; so it was that the Putto was brought to Rome and buried in a vineyard to make it “antique” and sell it as a Roman artefact. Michelangelo was probably unaware of it.

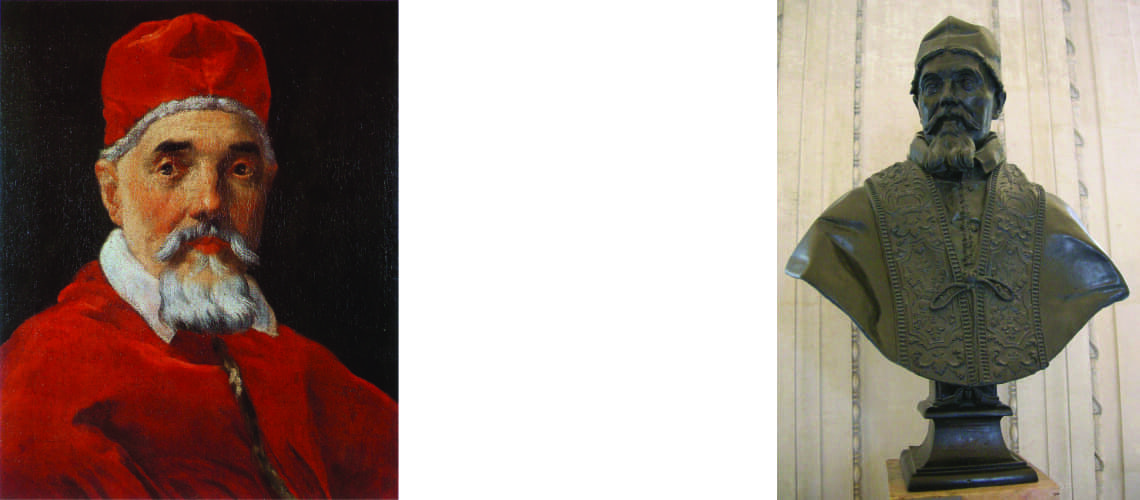

The trick was successful, so much so that it was purchased by Raffaele Riario, Cardinal of San Giorgio, a famous art collector, through the intermediary Baldassare del Milanese for 200 ducats. But the Milanese only brought Michelangelo an advance of 20 ducats.

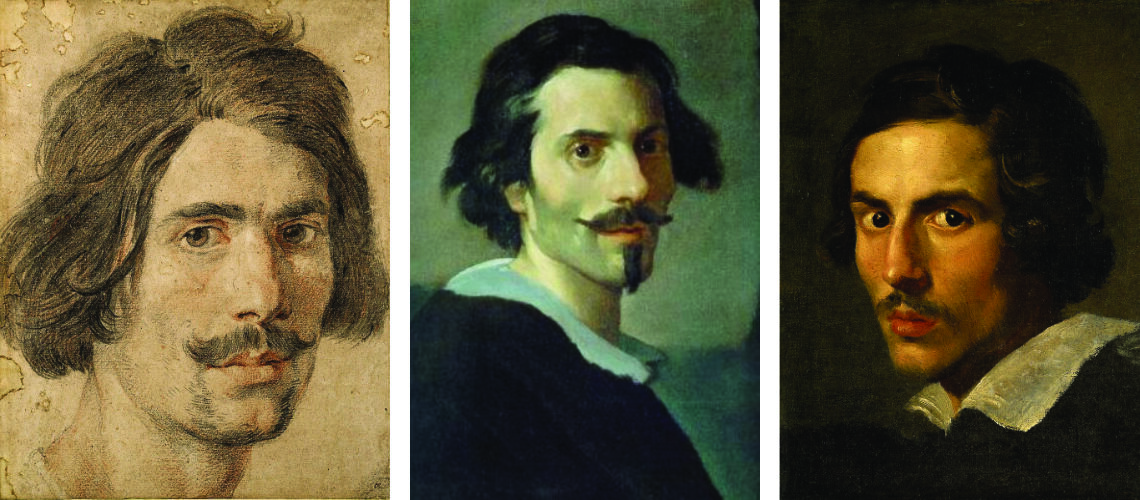

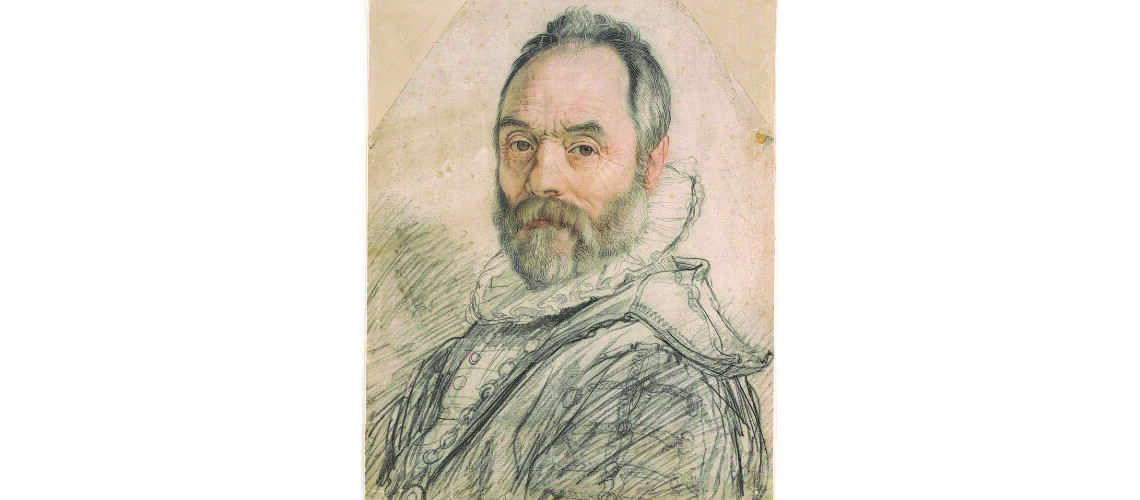

Cardinal Raffaele Riario (center), Raphael, 1512, Bolsena Mass, Vatican Rooms

Riario realized he had been cheated, but the work was so perfect that instead of wanting his money back he wanted to meet the artist who had sculpted it. He then sent his banker friend Jacopo Galli to Florence to bring the author of the Putto to Rome. Galli convinced Michelangelo, unaware of the scam, that having arrived in Rome in the presence of the cardinal with a letter of introduction from Lorenzo dei Medici the Popolano, having only had 20 scudi in Florence, he wanted his sculpture back.

Riario became furiously angry with Michelangelo, saying that he had paid for it and it belonged to him.

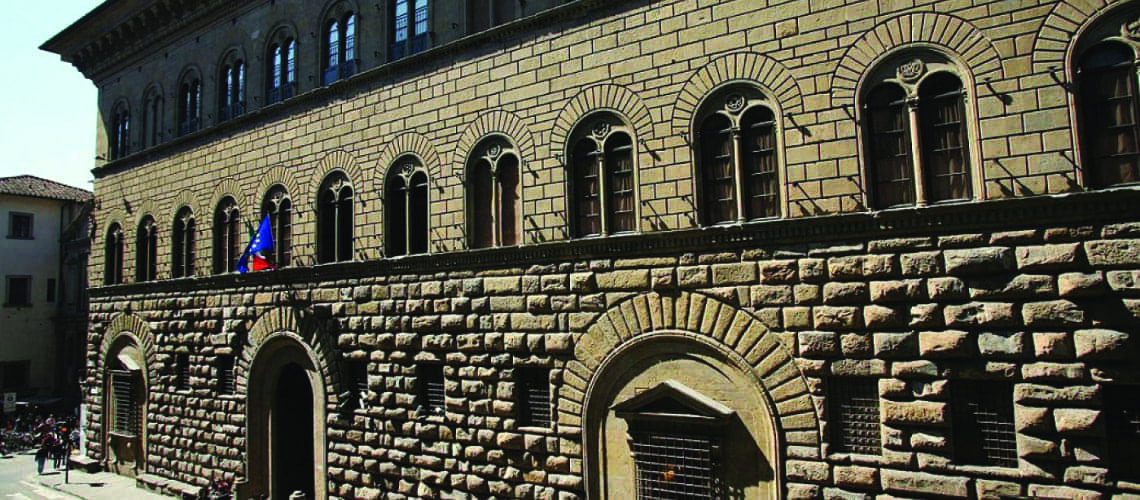

It was with this event that Michelangelo saw a new world of work open up in Rome largely through Galli, a very important and influential banker, who hosted him in his palace.

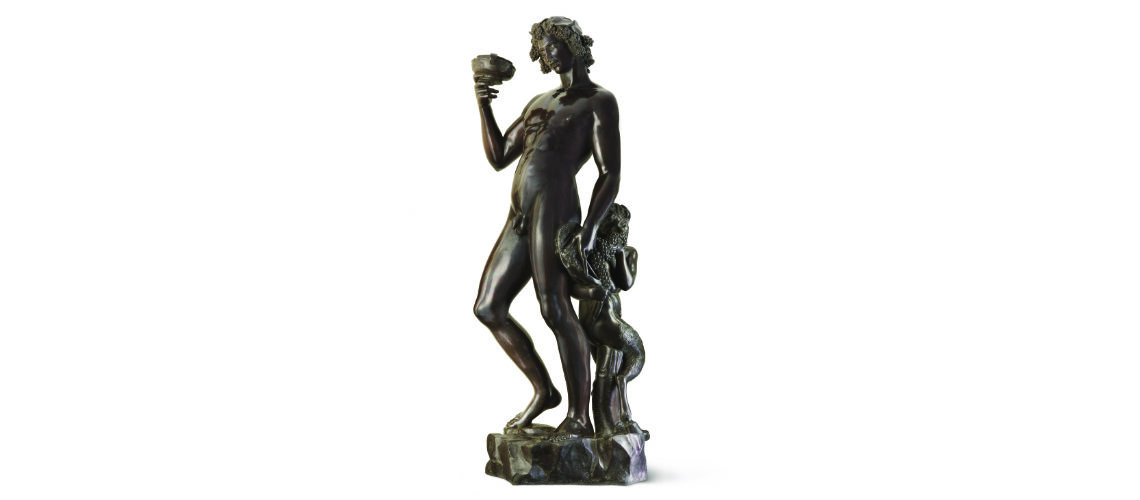

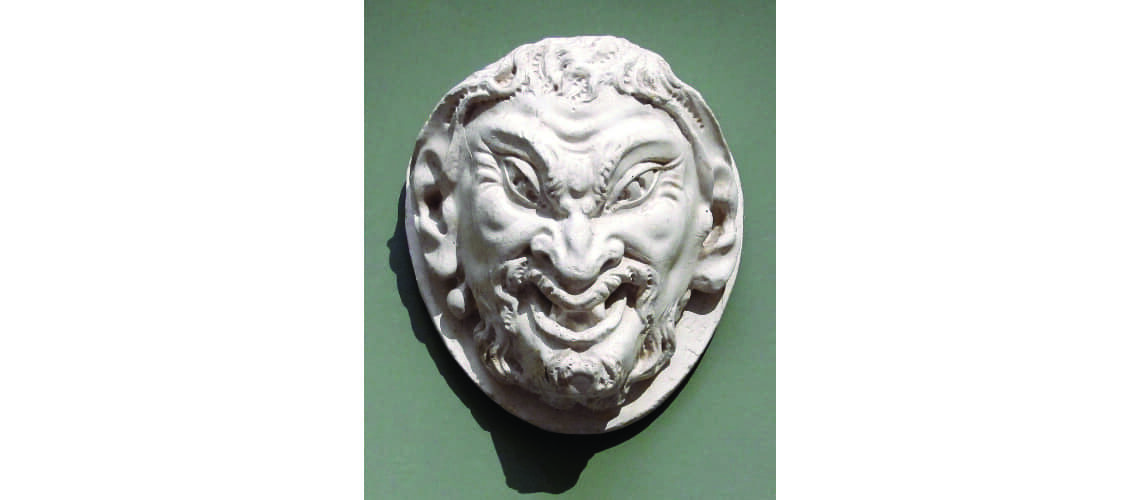

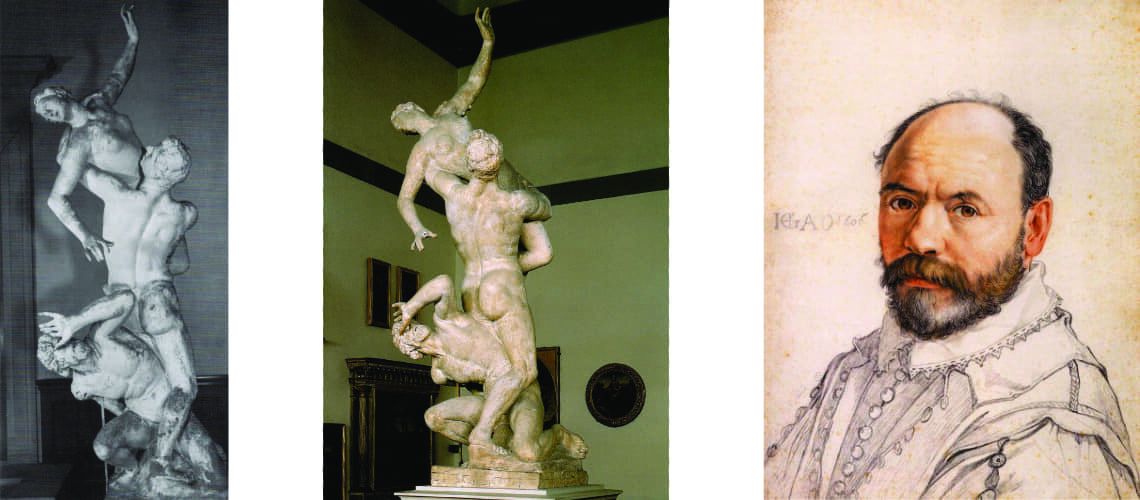

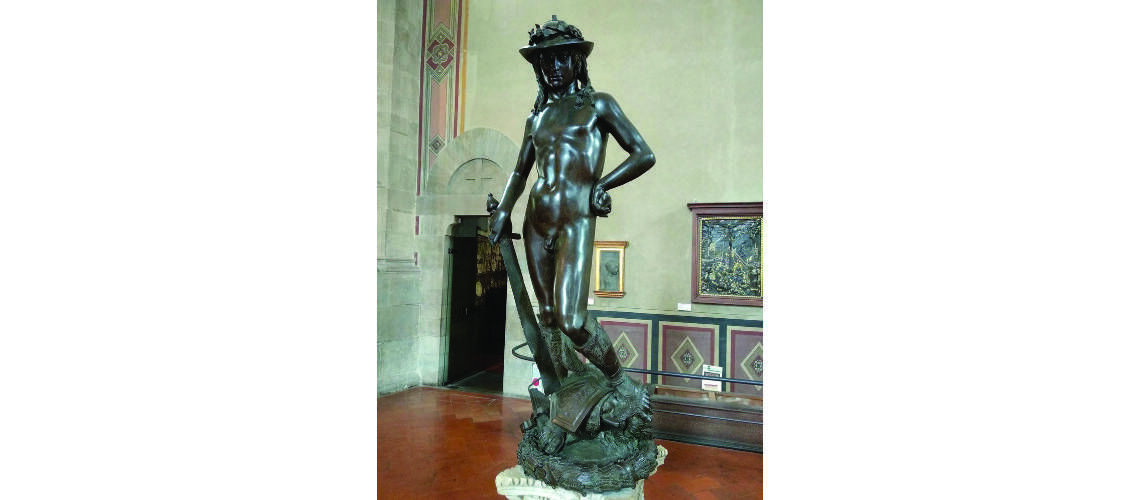

The Bacchus

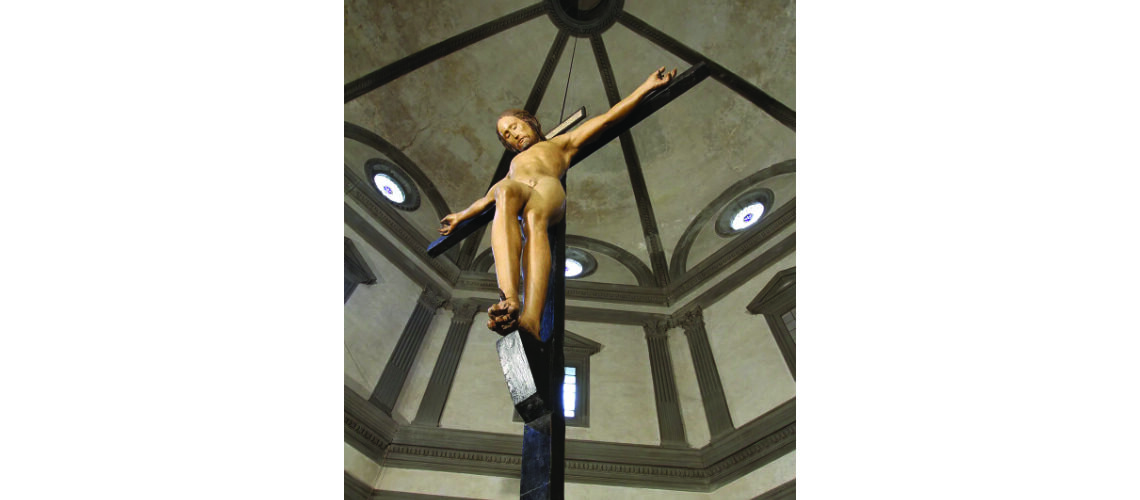

And in fact a few days things began to go better: on 4 July 1496 Cardinal Riario asked him to sculpt a pagan work for him, the BACCHUS. He completed it in a year, delivering it in 1497.

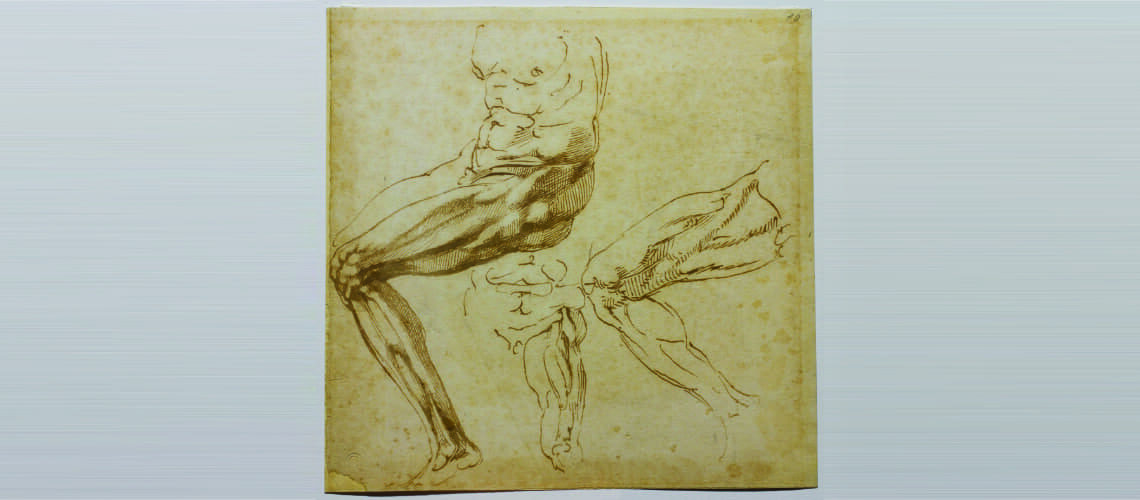

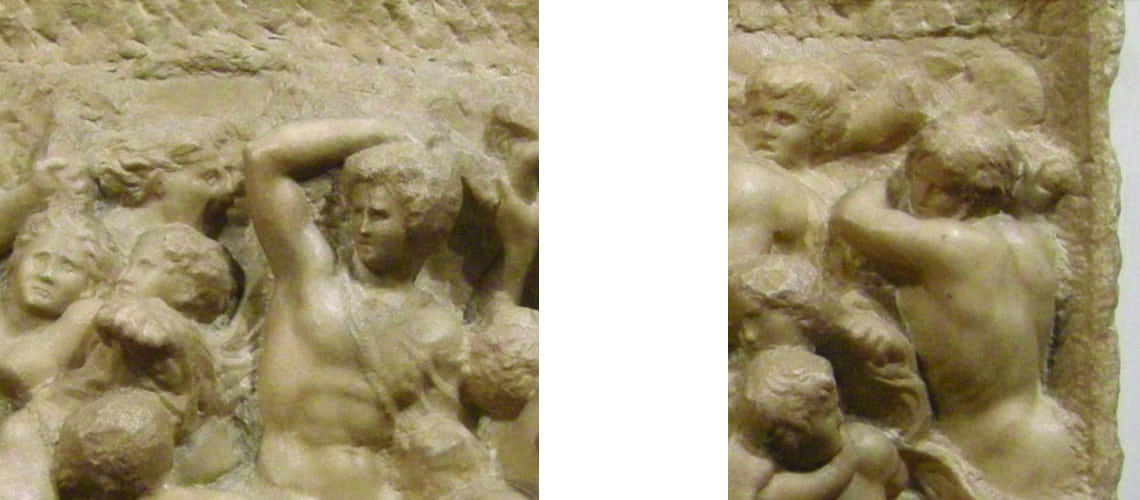

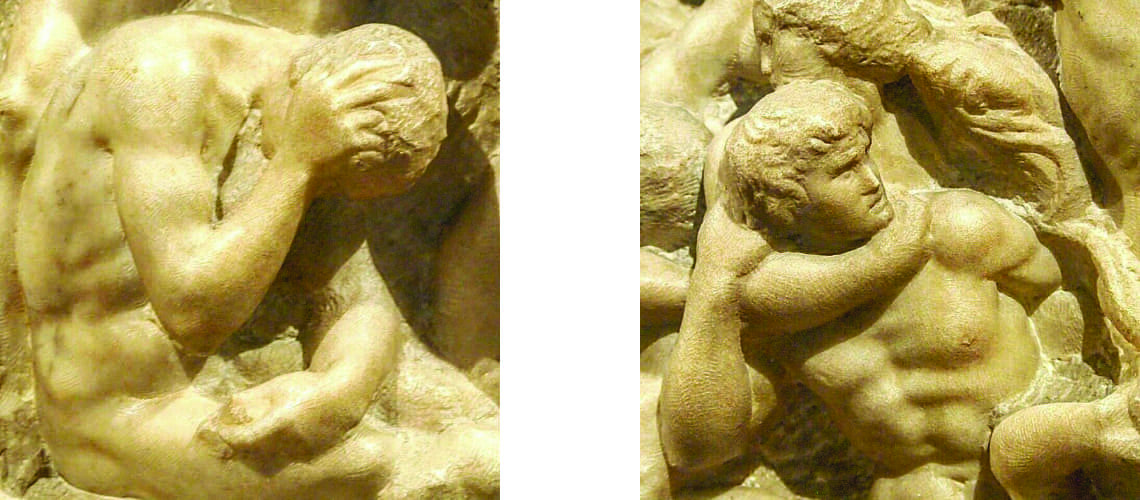

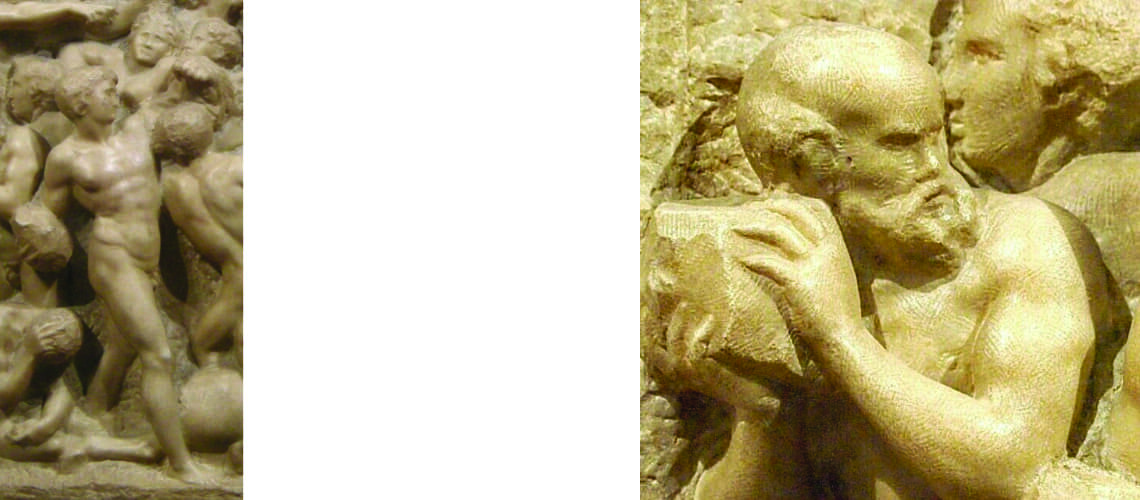

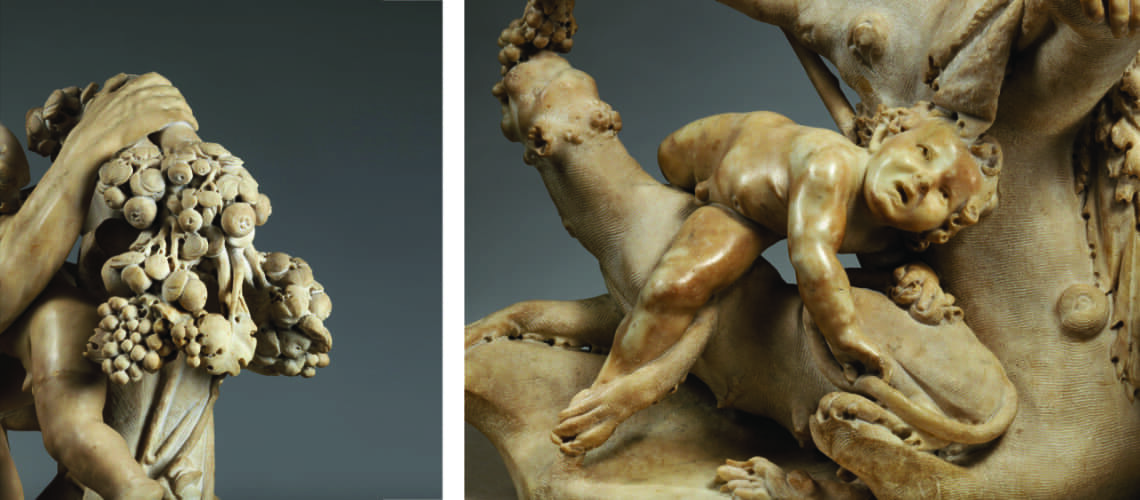

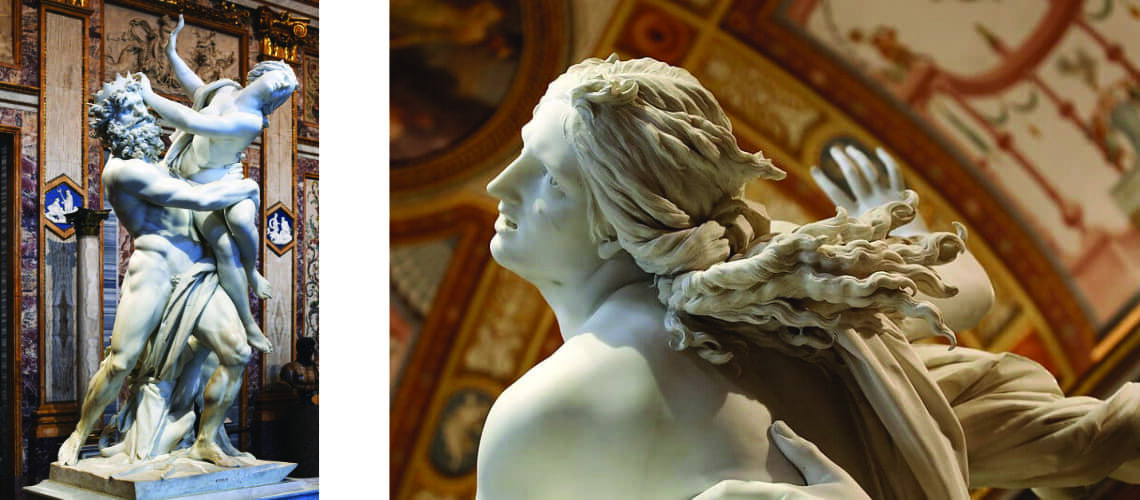

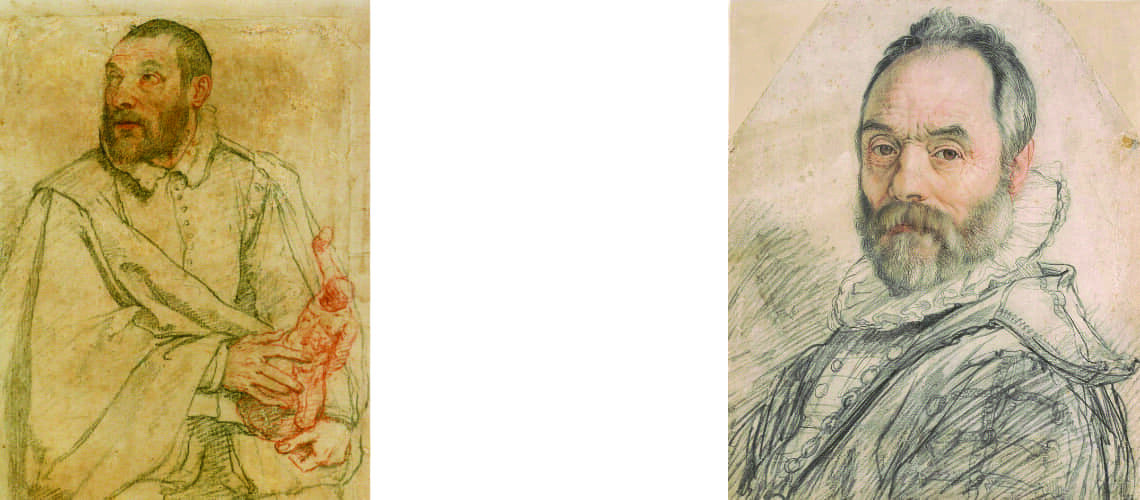

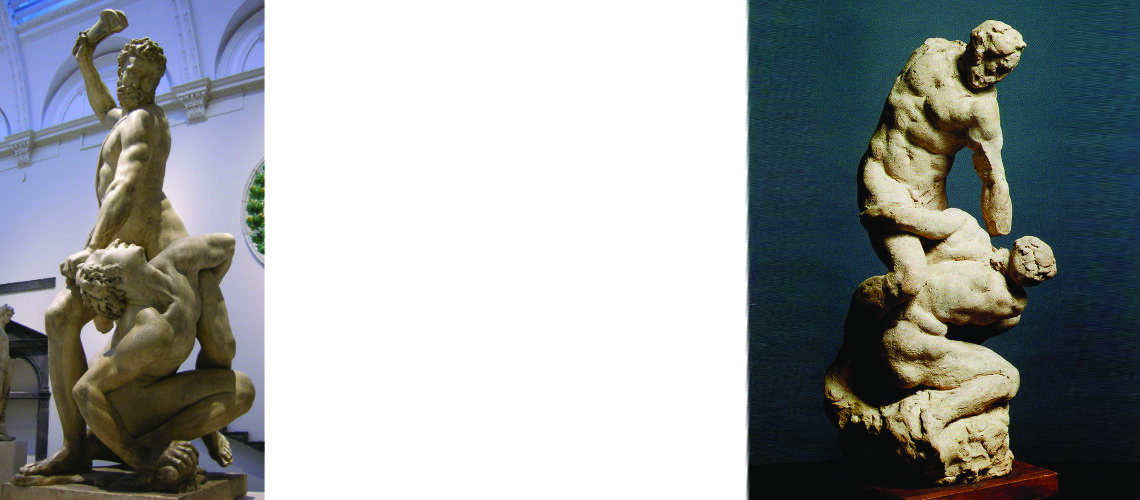

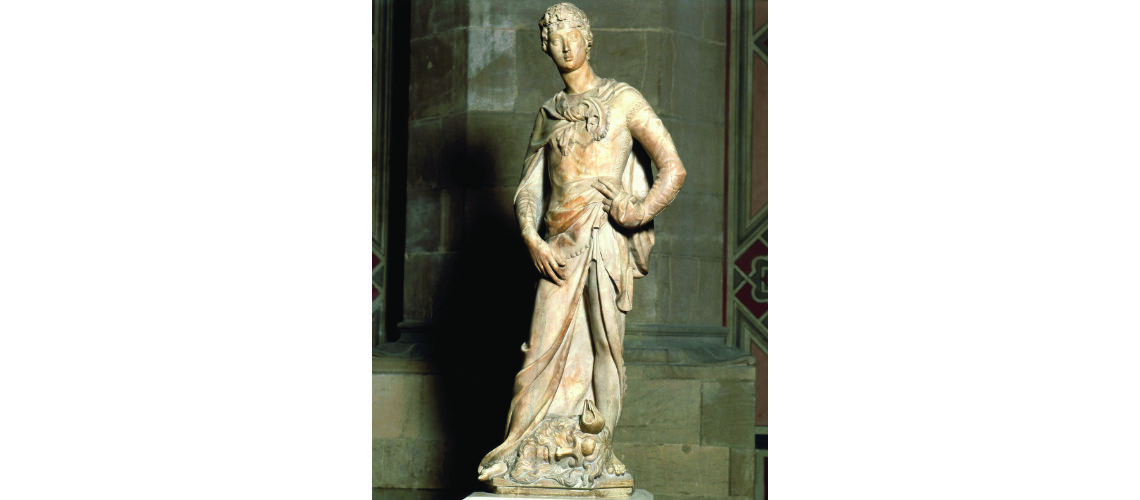

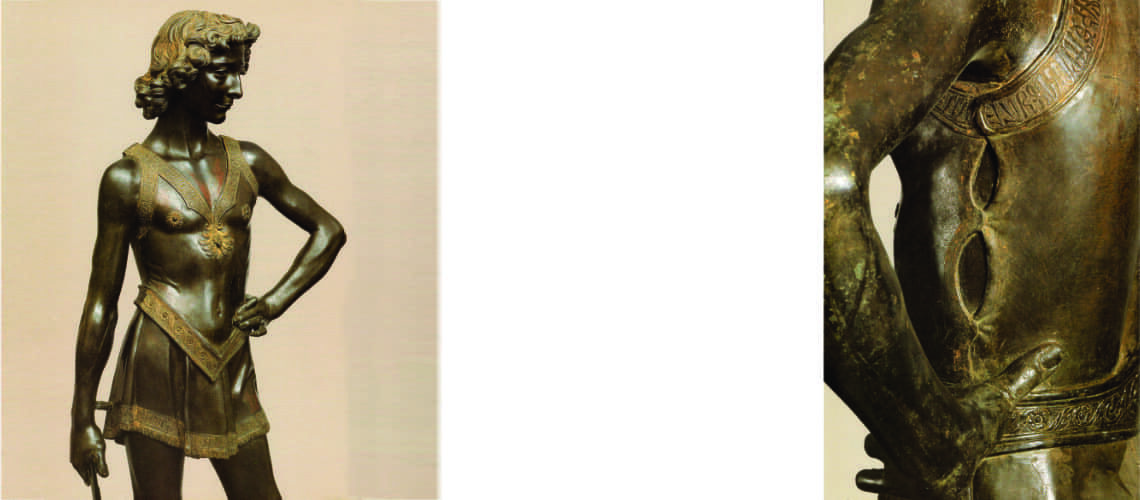

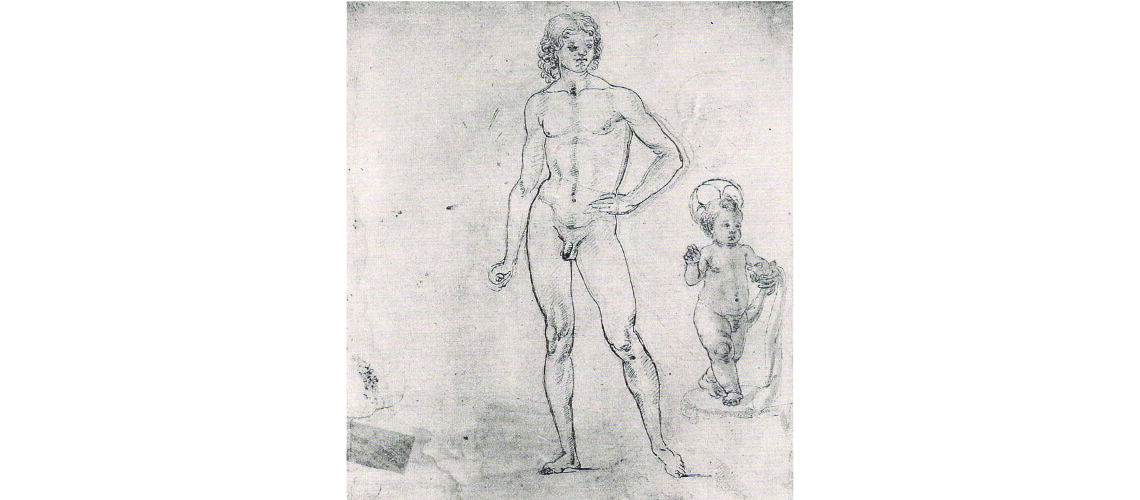

The mythological divinity is represented in a naturalistical way with the insecure gait of a young god drunk on wine, the contrapposto pose is slightly unbalanced, the head bent and the eyes distorted by the liquor, the body is soft and slightly feminine also highlighted by the belly slightly swollen also due to drinking. He holds the cup of wine in his hand, and two bunches of grapes hang between his curls. With his other hand he holds the leopard skin, an animal dear to the god.

Hidden behind him, a young satyr leaning on his left leg in a seductive pose eats grapes sitting on a cut tree trunk. The beautiful satyr also has a function of support and reinforcement of the work whose weight falls on the leg on which the satyr rests.

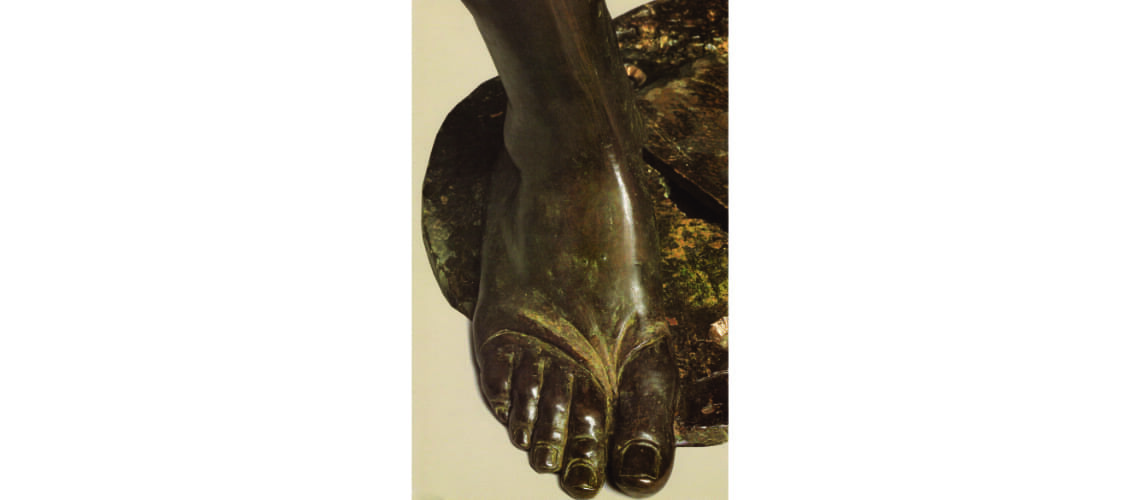

Michelangelo, Bacchus, Bargello Museum, detail

Michelangelo, Bacchus, Bargello Museum, detail

Cardinal Riario rejected the work, which was too little similar to the Roman depictions of Dionysus and therefore too lascivious for a member of the Church.

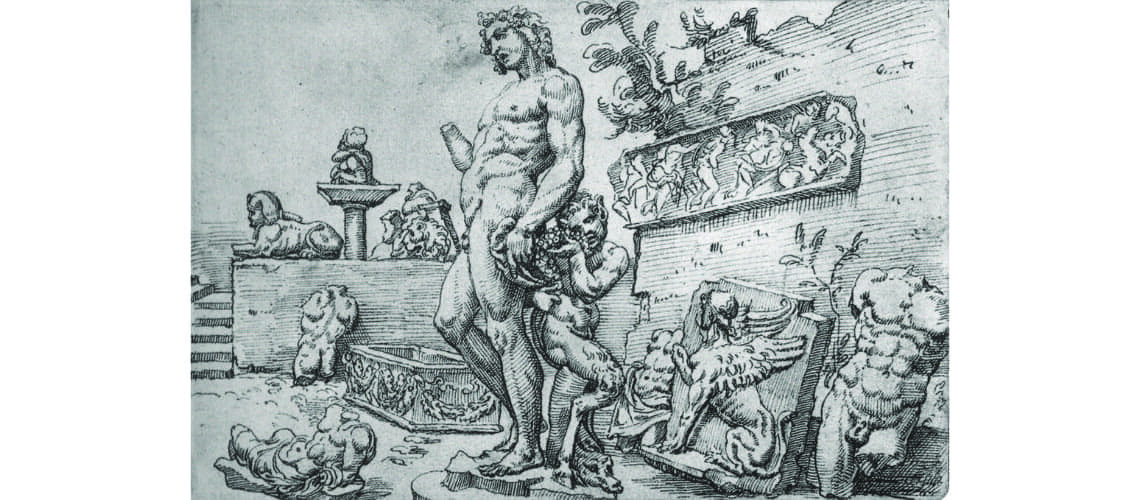

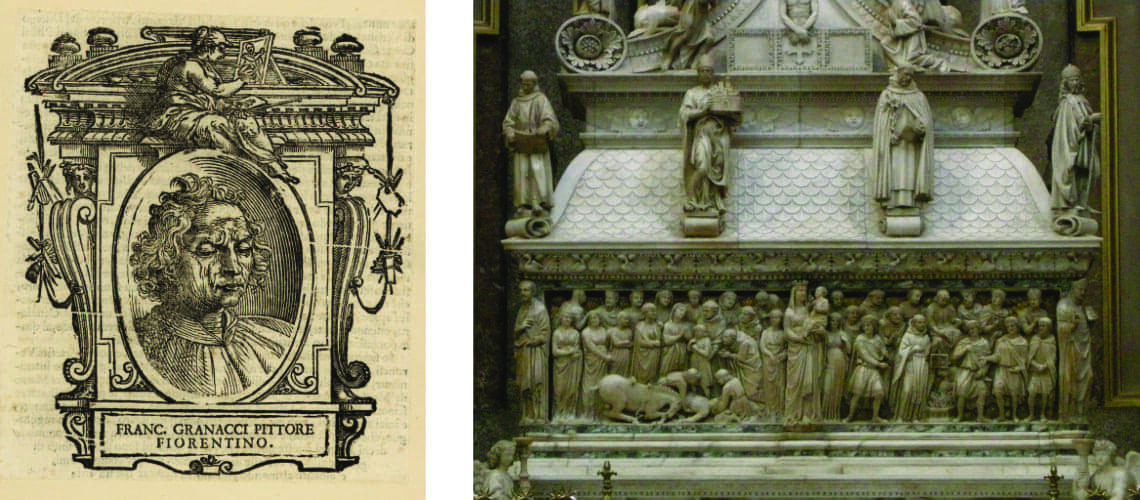

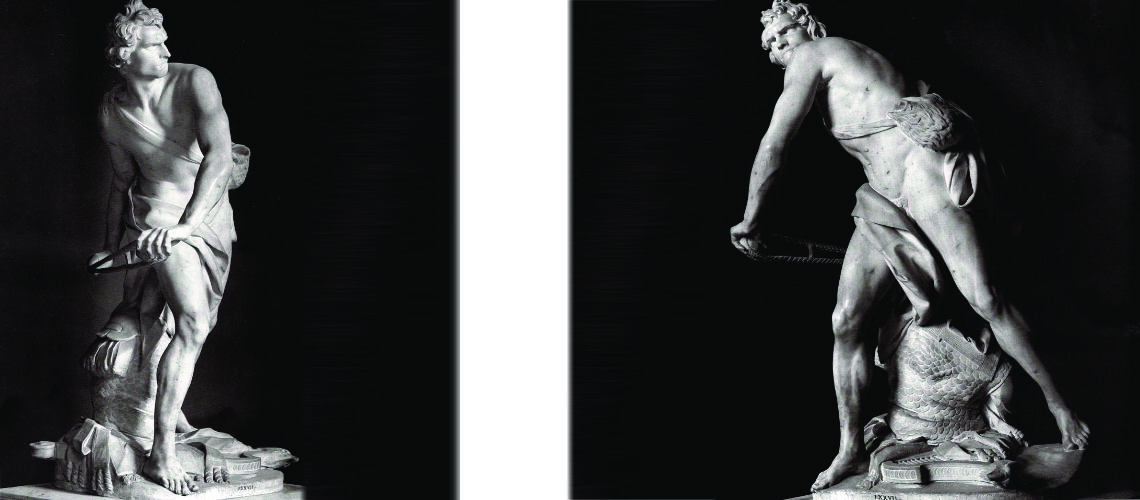

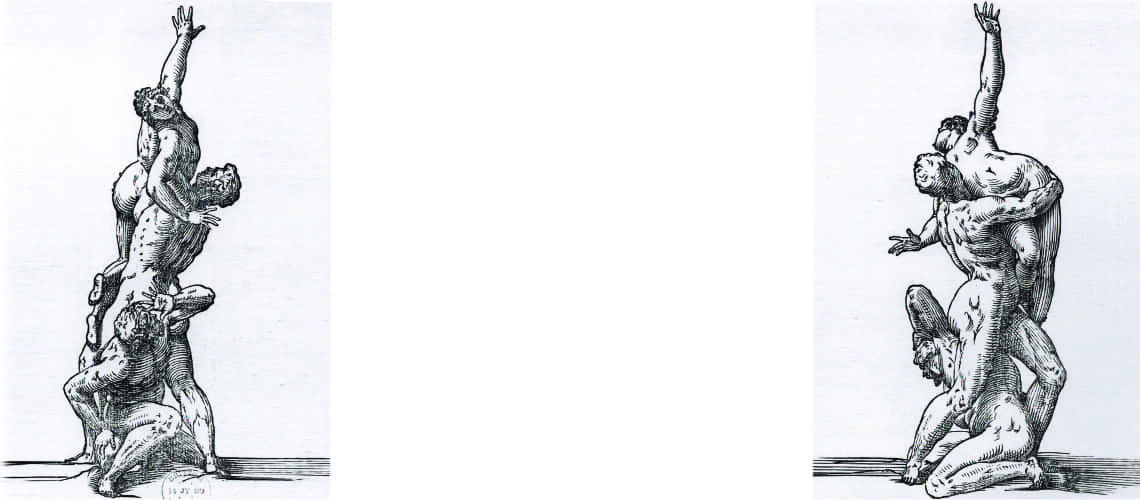

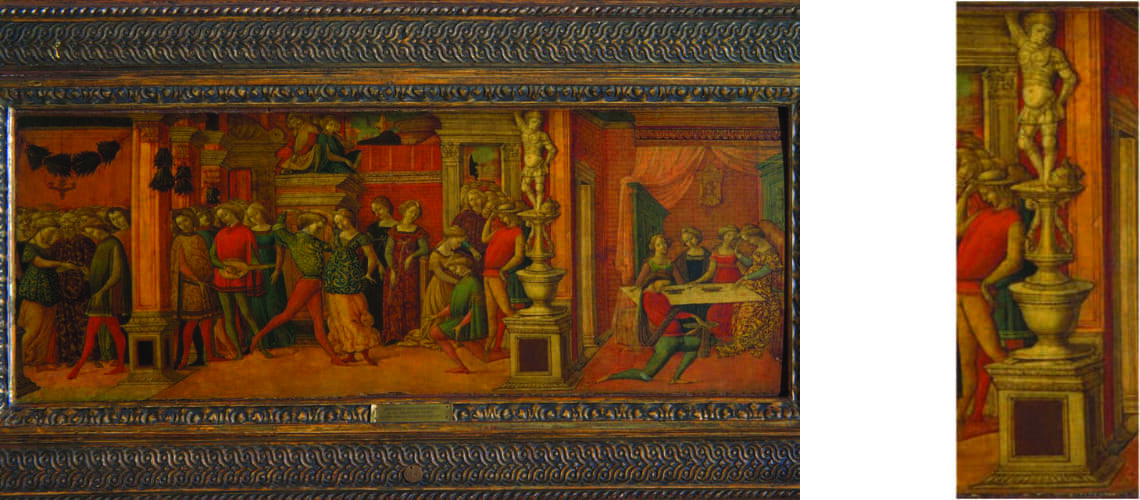

The banker Galli collected it with great pleasure and placed it in the center of his garden. The Dutch painter Maarten Van Heemserck saw the work in the Riario garden in 1532 and drew it. The cup and the right hand appear missing and the penis also appears to have been broken: the hand and cup seen today are an ancient addition.

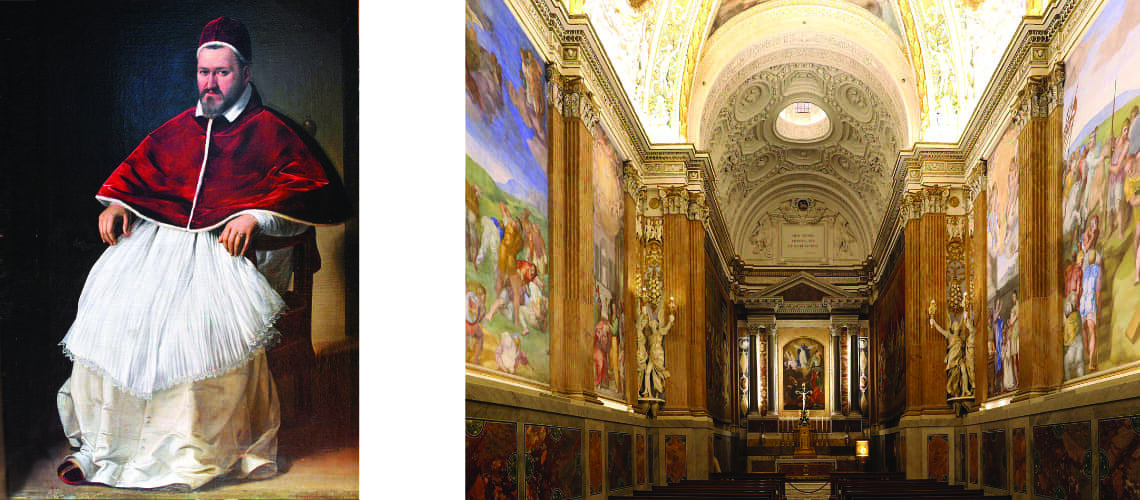

Drawing by Maarten van Heemskerck, 1535, The Bacchus in the Riario collection of ancient works

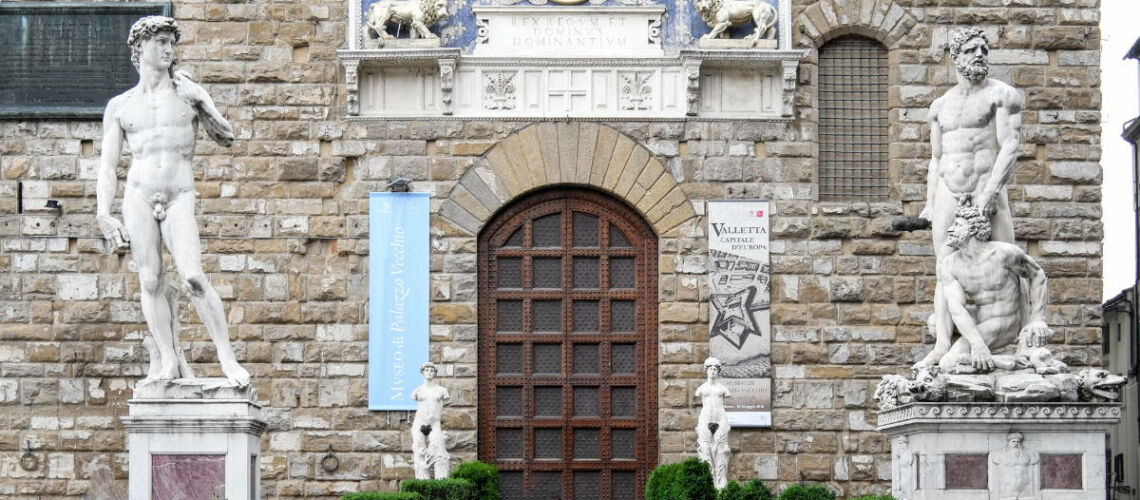

Bacchus is preserved and exhibited at the Bargello Museum.

Michelangelo’s Bacchus exhibited at the Bargello Museum

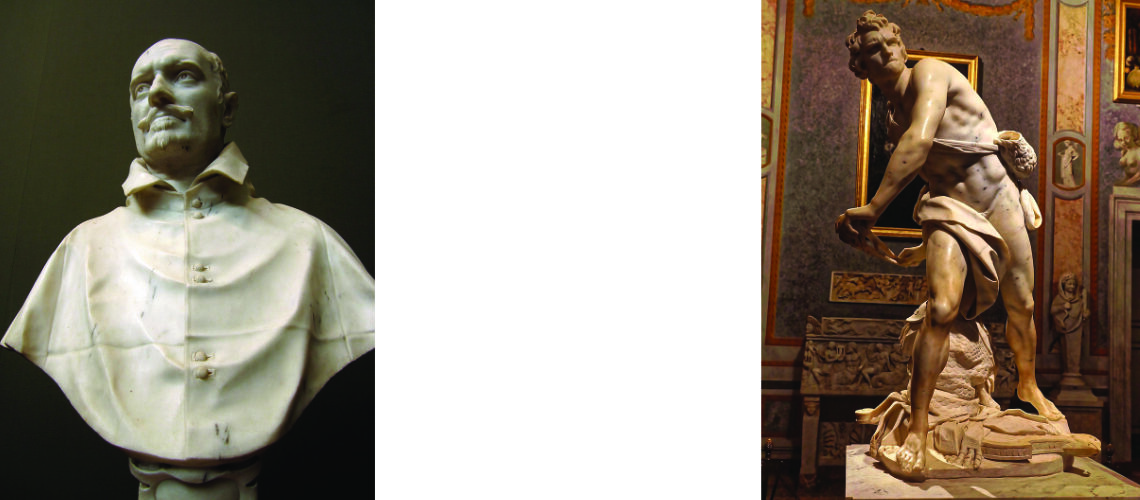

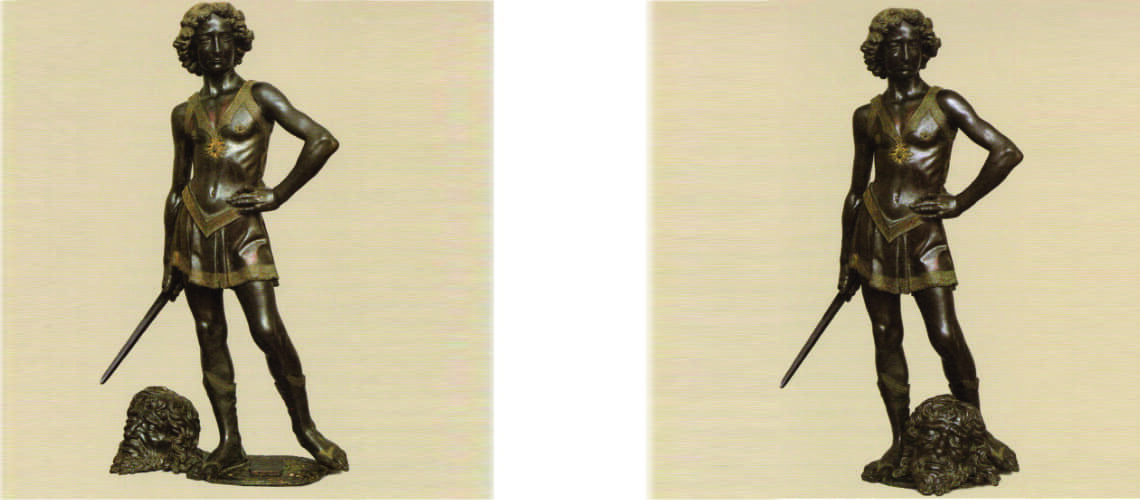

Posthumous statuary bronze casting from a cast made on the original by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry of Florence