The Holy Door

Part I

During the Jubilee, the Pope’s opening of the Holy Door of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican is the universal invitation to enter the house of God. The Holy Door opens at the first vespers of Christmas Eve, the day Jesus was born, who came to open the door of heaven which leads to salvation.

Storia del Giubileo

Before the actual Jubilee there were similar forms of plenary indulgence: the oldest known was the Jacobean Holy Year instituted by Pope Callixtus II in 1122 and 1126, so to obtain the forgiveness of all sins, pilgrims had to go to Santiago de Compostela.

In 1294 Pope Celestine V issued the Bull of Forgiveness for which by visiting the church of Santa Maria di Collemaggio in the city of Aquila between 28 and 29 August, he obtained the “Perdonanza”, that is, the plenary indulgence.

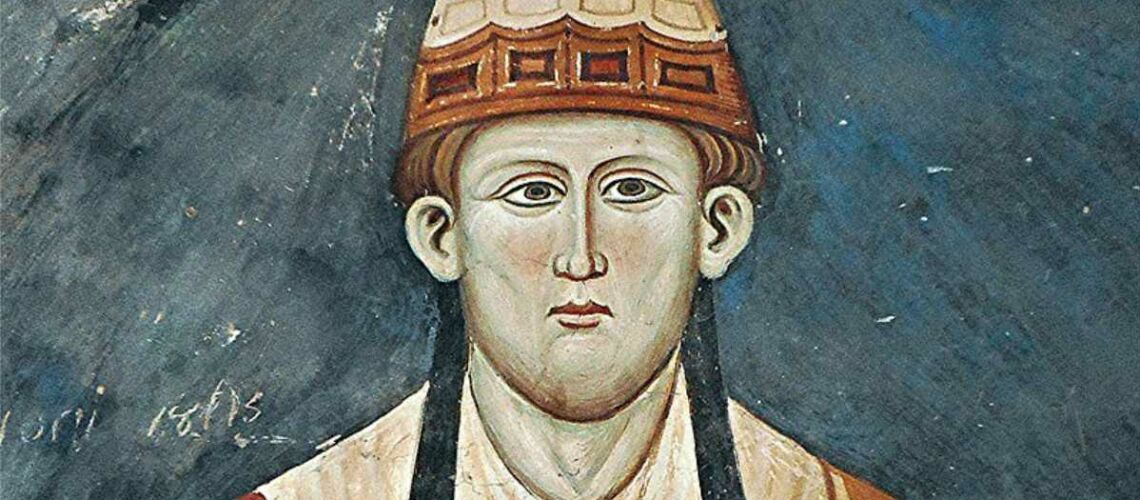

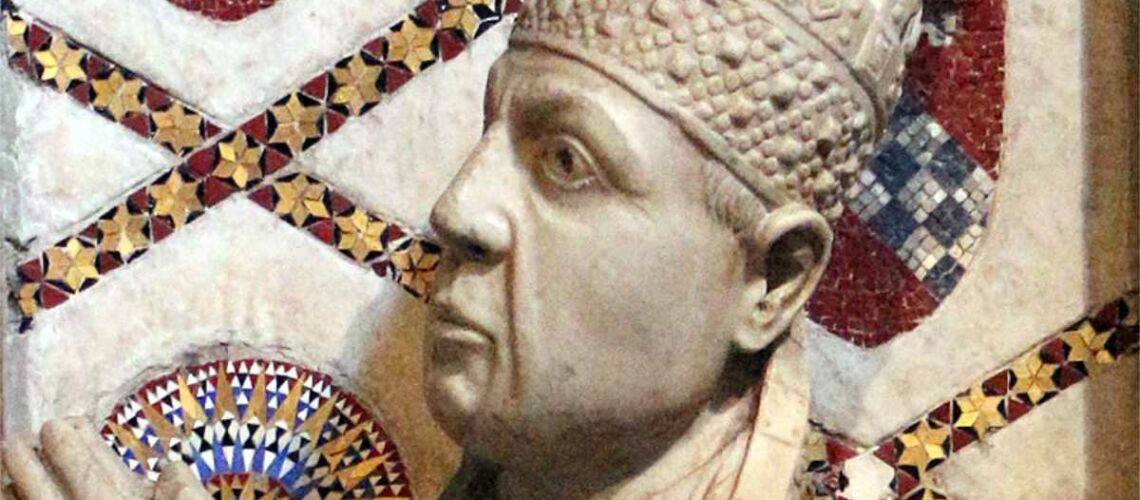

Pope Boniface VIII, in the wake of the legend of the “Indulgence of the Hundred Years” known since the time of Pope Innocent III,

on 22 February 1300 with the bull “Antiquorum habet fida relatio” he announced the Jubilee with retroactive effect to 24 December 1299, also establishing that it would have to be repeated every 100 years. The bull was engraved on a marble slab and affixed to the portico of the Vatican Basilica. And the three Leonine verses were added to his copies sent throughout the Catholic world:

Annus centenus Romae semper est iubileus

Crimina laxantur cui poenitet ista donantur

Hoc declaravit Bonifacius et roboravit

(The hundredth year in Rome is always a jubilee year / Sins are absolved and penalties condoned / This declared Boniface and confirmed.

In fact, there was a tradition according to which, since ancient times, a pilgrimage to St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome performed on January 1 of the first year of each new century would have resulted in a plenary indulgence. The only news that this rite was in use since 1200 is reported in the work “De centesimo sive Jubileo anno liber” report of the first Jubilee of 1300, by Jacopo Caetani degli Stefaneschi, canon of San Pietro: he writes that an old man of 108 years that, when questioned by Boniface, he asserted that 100 years earlier, on 1 January 1200, at the age of only 7, together with his father he would have gone before Innocent III to receive the Indulgence of the Hundred Years.

While the leaden seals of the bulls of Boniface VIII are known, the first medal of this pope dates back to the 1400s and bears the Holy Door on the back.

It is believed that among the anonymous coins issued by the Roman Senate during the thirteenth century, the so-called silver “sampietrini” were minted around 1297 precisely in anticipation of the Jubilee of 1300.

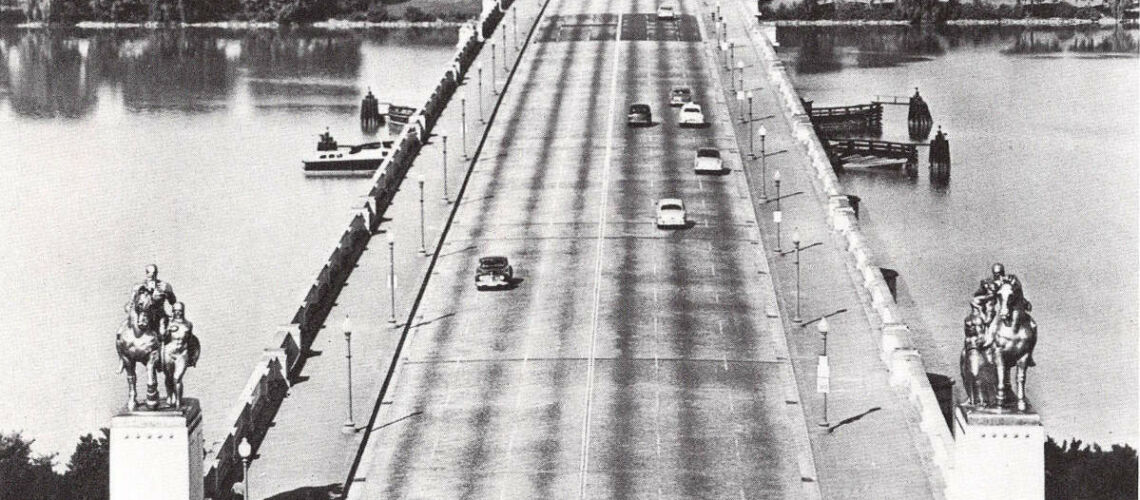

throughout Christianity there was an enormous influx of believers who went to St. Peter’s Basilica, as Dante recalls in verses 28-33 of the eighteenth canto of the Inferno:

Come i Roman per l’esercito molto

l’anno del Giubbileo, su per lo ponte

hanno a passar la gente modo tolto

che dall’un lato tutti hanno la fronte

verso il Castello e vanno Santo Pietro

dall’altra sponda vanno verso il monte…

so it was necessary to create a two-way traffic on the Sant’Angelo bridge so as not to hinder coming and going. The chronicles tell us that also in Florence, due to the great multitude of pilgrims who came and went from Rome, a metal railing was applied in the center of the Ponte Vecchio to regulate the flow of wayfarers.

Instead of every hundred years, the Jubilee was proclaimed after 50 years: Pope Clement VI on 18 August 1349 published, from Avignon, the bull “Unigenitus Dei Filius” which fixed the beginning of the Jubilee on 25 December 1350, despite the famous plague epidemic of 1348, the one described by Boccaccio in the Decameron. And he arranged that it should be repeated every 50 years, instead of the 100 established by Boniface VIII.

Matteo Villani who continued his brother Giovanni’s “Chronicle” tells us that between Lent and Easter one million two hundred thousand faithful visited Rome, and at Pentecost eight hundred thousand. Figures that seem very unlikely.

Pope Urban VI, with the bull “Salvator Noster Unigenitus Jesus Christus” of 8 April 1389, established that the Jubilees were to be called every 33 years instead of every 50. He exceptionally arranged to carry it out in 1390, but died in 1389; the successor Pope Boniface IX proclaimed it in that year despite the schism and the condemnation of the antipope Clement VII.

Between popes and antipopes Martin V established a Jubilee for Christmas 1423, and an anonymous chronicler from Viterbo writes that “he opened the holy door of S. Giovanni in Laterano”, that is, he created a new door in the basilica called for the first time “Porta Santa” which opened for the first time in that year.

Niccolò V wanted to return to the Jubilees 50 years apart from each other, indicating that of 1450 which had an enormous echo with an equally enormous presence of faithful from all over Europe, so much so that food and lodgings were not enough. And also for this Jubilee the Holy Door was opened in the Basilica of the Lateran, as the Florentine merchant Giovanni Rucellai writes in his Zibaldone, confirming what had already been declared by the anonymous Viterbese for 1423.

Pope Paul II brought the interval between the Jubilees to 25 years, indicating it for 1475, calling it the “Holy Year”, a term which has since joined that of “jubilee year” or Jubilee.

The possible presence of a Holy Door both in San Pietro and in San Paolo Fuori le Mura and in Santa Maria Maggiore is not clear until the pontificate of Alexander VI. Authors argue that they were even present before the 1300s, others that the opening and closing of the Holy Door in the Vatican basilicas would have begun precisely with Alexander VI.

Alexander VI Borgia proclaimed the Jubilee of 1500.

The master of the papal chapel since 1484 Giovanni Burcardo (Johannes Burckardus) who wrote

the “Libri Caeremoniales”, a chronicle of the Vatican ceremonies, tells us that the Holy Door was created for the first time in St. Peter’s Basilica by Pope Alexander VI Borgia on the occasion of the Jubilee of 1500, which he proclaimed in March 1499 with the Inter Multiples bubble; for the occasion he also had a new road opened, the Via Alessandrina (destroyed in the 1930s).

And in fact with the bull “Inter curas multiplices” Alexander VI announced the Jubilee for Christmas and ordered the simultaneous opening of the Holy Door of St. Peter’s and of the other three patriarchal basilicas: San Paolo, Lateranense, Santa Maria Maggiore. And he added “… with our hands we will open the Door of the Basilica of Blessed Peter…”.

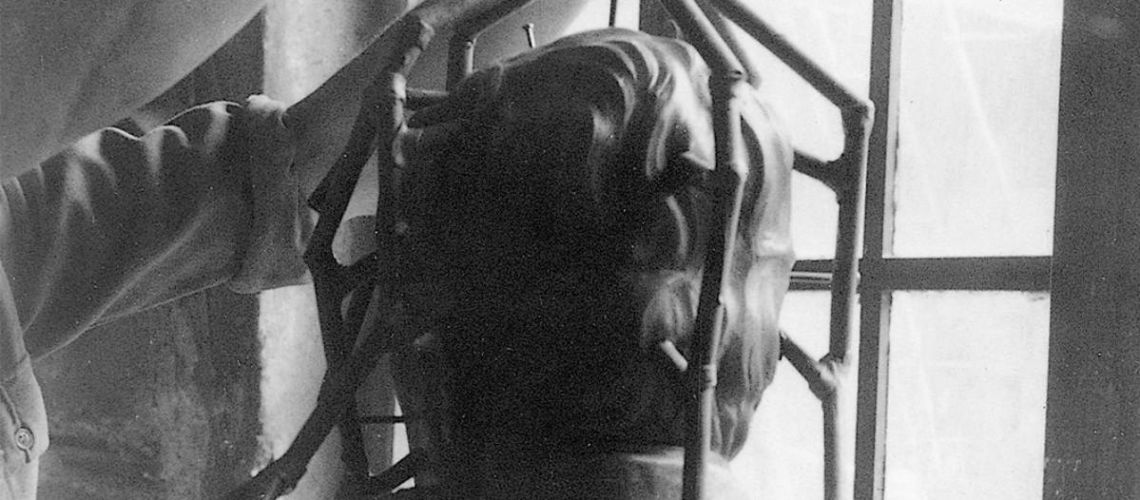

A new masonry door was built in St. Peter’s Basilica, but prepared so that during the Jubilee ceremony it would be easy for the pope to break a small central part with three hammer blows. The rest of the gate was demolished by the masons. The first to enter the church was to be the pope. Although Alexander VI perhaps did not create the ceremony of opening and closing the Holy Door from scratch, he gave it first order and uniformity by establishing a solemn and rigid ritual in the rules to be observed. It was Alexander VI who also called the Jubilee the Holy Year.

In this way he placed the Holy Door at the center of the jubilee rites, making this purely architectural element a profound spiritual value full of symbolic meanings.

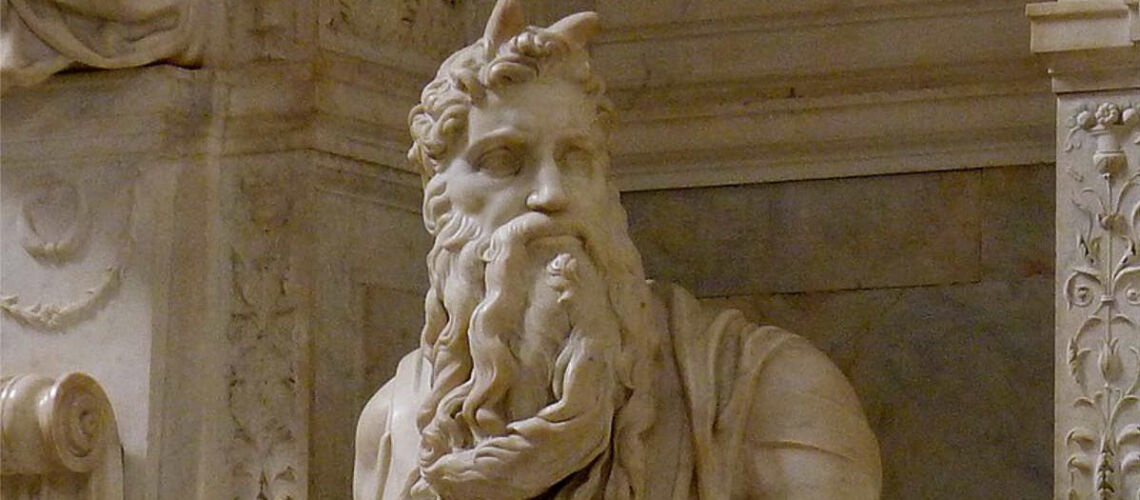

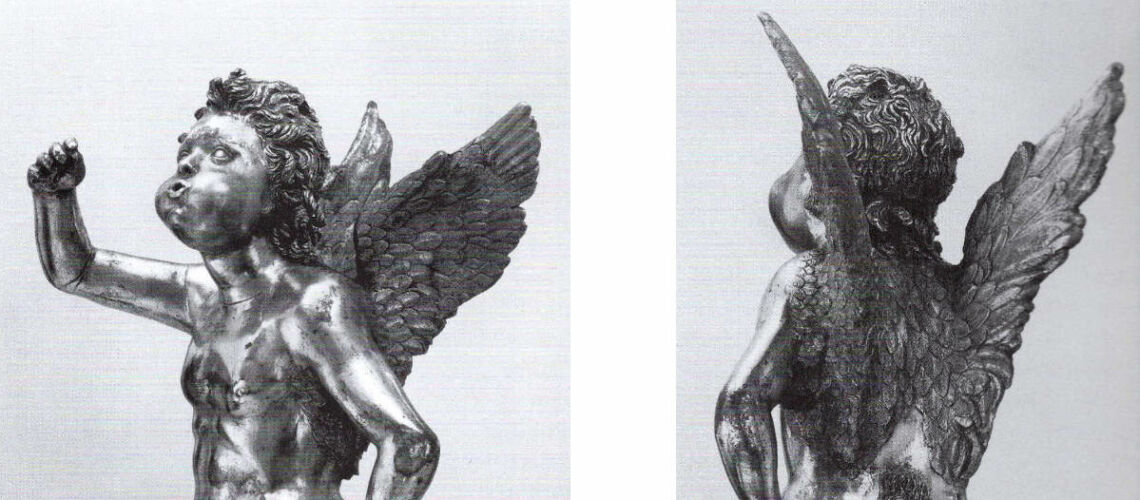

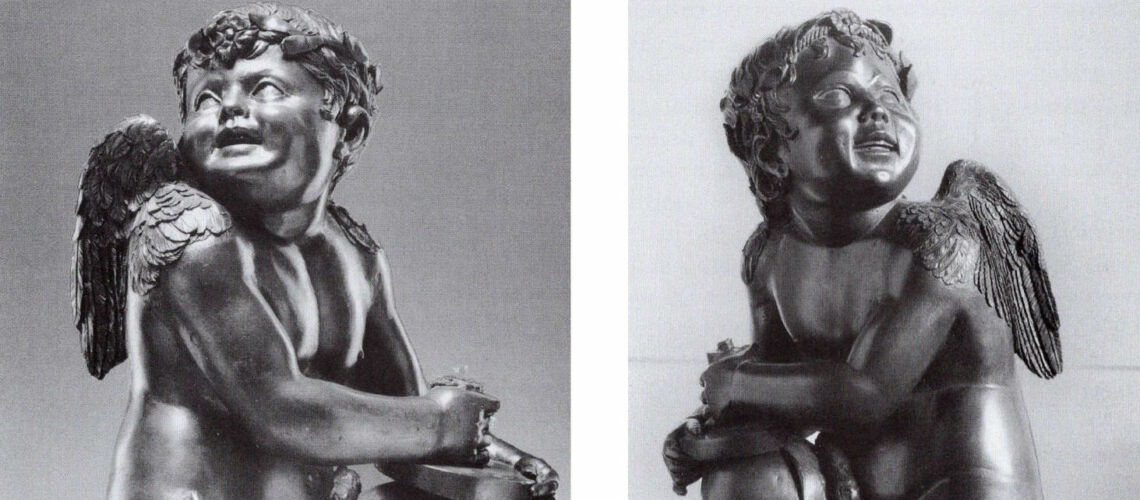

And the hammer with which the pope struck the door took on a symbolic-religious meaning, finding an ideal affinity with the rod with which Moses struck a rock in the desert from which water flowed for his people. Clement VII, in the following Jubilee of 1525, had the mason’s hammer used by Alexander VI replaced with one of solid gold or gilded silver, as Giorgio Vasari also confirms in his sixteenth-century “Ragionamenti”.

We know that before the Holy Year of 1625 Pope Urban VIII proposed to replace the walled up door in the opening and closing ceremony of the Holy Door with a wooden door fitted with hinges and the hammer with two keys, one gold and one silver.

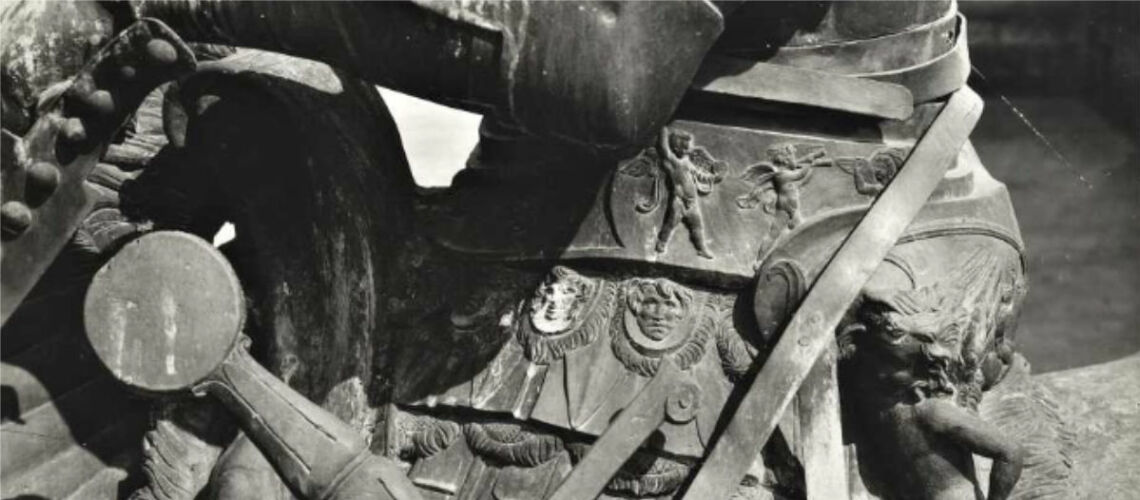

The first image relating to the opening of the Holy Door is the one minted on the reverse of the 5 ducats coin of 1525 of Clement VII.

From 1742 to 1752, a metal door with a wooden core was built, at the behest of Mons. Francesco Giovanni Olivieri, Secretary of the Reverenda Fabbrica, which replaced the wooden shutters of the Holy Door, where the two metal doors were inserted and placed which closed the niche of the Holy Face of the tabernacle in the ancient St. Peter’s. The two new doors had no artistic value, but were used to close the Holy Door during the various subsequent jubilees.